Legendary Pictures chairman and chief executive Thomas Tull wryly remarked back in the March 4, 2007 New York Times article on the Paradise Lost film project that his initial reaction to the prospect of making Milton’s seventeenth-century epic poem into a movie was, “Well, that’s going to make a lot of older folks relive bad college experiences.” Yet he came to believe that the film could be made appealing to a broad audience “if you get past the Milton of it all,” in the words of Tull, who explained, “if you get past the Milton of it all, and think about the greatest war that’s ever been fought, the story itself is pretty compelling…” Making a film adaptation of Milton’s masterpiece and proceeding to try and “get past the Milton of it all” was certainly a suspect sentiment, but what did Tull mean by this?

Milton’s Paradise Lost is certainly Milton’s Paradise Lost, which is to say, although the Puritan poet was retelling literally the oldest story in the book—the Fall of Man at the dawn of Creation—Milton’s presentation of this age-old tale in Paradise Lost was unique unto him. For one thing, as Milton states early on in the poem, his ambition was to outshine the classical epics of the Greek Homer and the Roman Virgil—“to soar / Above th’ Aonian Mount” (I.14–15)—with his own Christian-themed English epic. A byproduct of this aspiration was challenging the pagan epics on their own ground, Milton setting out to demonstrate that pagan heroism pales in comparison to Christian virtue—as personified in none other than God’s Son, “By Merit more than Birthright Son of God, / Found worthiest to be so by being Good, / Far more than Great or High…” (III.309–11). Thus, Milton declares in the proem to Book IX that he dismissed for his Christian epic the traditional epic subject of warfare, “hitherto the only Argument / Heroic deem’d,” which lamentably left “the better fortitude / Of Patience and Heroic Martyrdom / Unsung…” (IX.28–29, 31–33). Milton opted for the subject of “Man’s First Disobedience” (I.1), a subject he found “Not less but more Heroic” (IX.14) than those found in the Iliad and Odyssey of Homer and the Aeneid of Virgil, for through the primeval disobedience of Adam and Eve, the Son of God becomes the glorious savior of disobedient Man. This, for Milton, completely eclipsed the classical heroes’ martial valor, assumed in Paradise Lost by Milton’s Satan, “the proud / Aspirer” (VI.89–90) who is “by merit rais’d / To…bad eminence…” (II.5–6). (Of course, Milton’s demonization of the classical virtues via imbuing Satan himself with them was part of what made Milton’s Devil far more appealing than intended.)

Milton’s Paradise Lost is certainly Milton’s Paradise Lost, which is to say, although the Puritan poet was retelling literally the oldest story in the book—the Fall of Man at the dawn of Creation—Milton’s presentation of this age-old tale in Paradise Lost was unique unto him. For one thing, as Milton states early on in the poem, his ambition was to outshine the classical epics of the Greek Homer and the Roman Virgil—“to soar / Above th’ Aonian Mount” (I.14–15)—with his own Christian-themed English epic. A byproduct of this aspiration was challenging the pagan epics on their own ground, Milton setting out to demonstrate that pagan heroism pales in comparison to Christian virtue—as personified in none other than God’s Son, “By Merit more than Birthright Son of God, / Found worthiest to be so by being Good, / Far more than Great or High…” (III.309–11). Thus, Milton declares in the proem to Book IX that he dismissed for his Christian epic the traditional epic subject of warfare, “hitherto the only Argument / Heroic deem’d,” which lamentably left “the better fortitude / Of Patience and Heroic Martyrdom / Unsung…” (IX.28–29, 31–33). Milton opted for the subject of “Man’s First Disobedience” (I.1), a subject he found “Not less but more Heroic” (IX.14) than those found in the Iliad and Odyssey of Homer and the Aeneid of Virgil, for through the primeval disobedience of Adam and Eve, the Son of God becomes the glorious savior of disobedient Man. This, for Milton, completely eclipsed the classical heroes’ martial valor, assumed in Paradise Lost by Milton’s Satan, “the proud / Aspirer” (VI.89–90) who is “by merit rais’d / To…bad eminence…” (II.5–6). (Of course, Milton’s demonization of the classical virtues via imbuing Satan himself with them was part of what made Milton’s Devil far more appealing than intended.)

As if Milton’s theological aspiration wasn’t task enough, the poet included in Paradise Lost a significant political component as well. Paradise Lost was composed during the Restoration, the republican Milton writing—or dictating, actually, as Milton was at this point completely blind—amidst his dashed dreams of an English commonwealth free from the bondage of monarchal tyranny. Paradise Lost was subsequently infused with a strong antimonarchical message, and while Romantic radicals saw the regicidal Milton reflected in his arch-rebel Satan, who fashions himself as the “Antagonist of Heav’n’s Almighty King” (X.387), Milton repeatedly suggests that earthly monarchy came straight from Hell (II.672–73; IV.381–83; XII.24–74) as a sinful imitation of “Heav’n’s matchless King” (IV.41).

These complex literary, theological, and political positions embedded in Paradise Lost are part and parcel of “the Milton of it all,” but one would imagine that a film adaptation of Milton’s Paradise Lost would jettison these weighty issues in favor of the grandness of the story and the cosmic conflict of its outsized characters—“the greatest war that’s ever been fought,” as Tull put it—which would surely make for plenty of onscreen spectacle. Yet even certain aspects of Milton’s presentation of his story and characters would likely prove puzzling to modern-day film audiences. For instance, Milton prolongs his War in Heaven into a three-day conflict, Satan and his rebel angels, after suffering a terrible loss on the first day of battle, inventing cannons to even the odds on the second day (VI.469–634). Milton is at his most peculiar in Paradise Lost, however, when he (via the archangel Raphael) goes out of his way to explain the complexities of angelic anatomy and physiology (VI.344–53), including angelic digestion (V.404–13) and sexual intercourse (VIII.620–29).

Speaking of supernatural intercourse, one would have to imagine a film adaptation of Paradise Lost would excise the Satan, Sin and Death episode, wherein Satan’s daughter Sin explains that when she burst full-grown from her father’s haughty head (II.749–58), Satan saw in his offspring his own “perfect image” (II.764) and in turn “Becam’st enamor’d” (II.765), copulating with Sin and inadvertently creating Death, Satan’s “Son and Grandchild both” (X.384). Death, Sin relates, tore from her womb and proceeded to rape his mother, deforming Sin’s lower half into a serpentine monstrosity (II.761–802). Paradise Lost’s incestuous and monstrous unholy trinity is surely part of “the Milton of it all,” but would a film adaptation dare to go there? Well, as revealed by the demonic concept art of Dane Hallett and the Milton on Film book by Paradise Lost’s script consultant Eric C. Brown, Sin was set to appear in the film, albeit in an altered dynamic (Milton’s devoutly loyal angel Abdiel was recast as “the Angel of Death,” who would surely replace Sin’s incestuous son). What’s more, it is safe to assume that Tull’s comment about “get[ting] past the Milton of it all” was not necessarily about Paradise Lost’s challenging language—seventeenth-century English epic verse rife with Latinisms—as Sin, according to Brown’s book, “was so insistently Miltonic in her speech as to be dubbed ‘like Yoda times a thousand.’ ”1 Perhaps the Paradise Lost film was more Miltonic than Tull anticipated?

Yet perhaps the need to “get past the Milton of it all” pertained more to the character of Milton’s Satan than to his Sin or Death. “The depiction of Satan may be a polarizing one among scholars,” noted Michael Joseph Gross in his 2007 New York Times article. “Some, in line with Romantic poets like William Blake, will want the dark prince to be the hero; others won’t be happy unless Satan is a self-deceiving hypocrite, and the story an education in virtue and obedience.” The latter was certainly what Milton the Puritan set out to accomplish, but the former was undeniably what Milton the poet ended up achieving. “Milton gives the Devil all imaginable advantage,” observed Percy Bysshe Shelley in his unpublished Essay on the Devil and Devils (ca. 1819–20), Shelley questioning Milton’s status as a Christian and speculating that he may have masked his Satanic sympathies within a literary work so as to evade the inevitable persecution such heresy would call down, given the oppressive climate in which Milton was writing: “Thus much is certain, that…the arguments with which he [Milton’s Devil] exposes the injustice and impotent weakness of his adversary are such as, had they been printed distinct from the shelter of any dramatic order, would have been answered by the most conclusive of syllogisms—persecution.”2

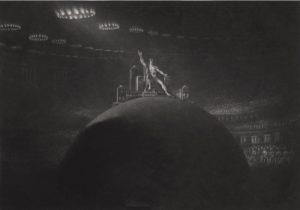

Shelley’s extreme position that Milton was a conscious Satanist is unwarranted, and the more plausible (and frankly more intriguing) theory is derived from the infamous dictum of Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790–93): Milton was “of the Devils party without knowing it[.]”3 Either way, the Romantic Satanists’ reading of Paradise Lost, to be fair, did “get past the Milton of it all” insofar as they liberated Milton’s Satan from the Christian confines of Paradise Lost—an epic poem designed by Milton to “justify the ways of God to men” (I.26)—which enabled the fallen angel to ascend as a Promethean Romantic hero. Then again, as far as the Romantic Satanists were concerned, Milton had with his Satan created a character—inadvertently or otherwise—so sympathetic and sublime that he was destined to break free from the pages of the poem. “As if misplaced in the ideological structure of Milton’s epic,” notes Peter A. Schock in his study of Romantic Satanism, “the figure of the fallen angel invited his own excision and insertion into different contexts,” and as a result

Milton’s Satan assumes in the Romantic era a prominence seen never before or since, nearly rivaling Prometheus as the most characteristic mythic figure of the age. A more active and ambiguous mythic agent than the bound, suffering forethinker and benefactor of humanity, the reimagined figure of Milton’s Satan embodied for the age the apotheosis of human desire and power.”4

Considering Milton’s Satan “the hero of Paradise Lost”—a phrase employed matter-of-factly by the Satanic School’s Byron and Shelley5—was for the Romantic Satanists entirely central to “the Milton of it all.”

If, in the end, “the Milton of it all” refers to the theological Puritanism of Paradise Lost, and if a Paradise Lost film that “get[s] past the Milton of it all” means that Milton’s Satan could be translated to the big screen as “the apotheosis of human desire and power” for our own age, as he was for the Romantic age, then from the perspective of a neo-Romantic Satanist it is to be wished that a Paradise Lost film “get past the Milton of it all.” It remains to be seen, however, whether the film adaptation of Paradise Lost—should it ever make it to theaters—will deliver the complex ambiguity of a Miltonic-Romantic Lucifer or Legendary’s Thomas Tull simply meant that Milton’s masterpiece would be reduced to a superficial angelic action film.

Notes

1. Eric C. Brown, Milton on Film (Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press, 2015), p. 332.↩

2. Percy Bysshe Shelley, Essay on the Devil and Devils, in Shelley’s Prose: or the Trumpet of a Prophecy, ed. David Lee Clark, pref. Harold Bloom (New York: New Amsterdam Books, 1988), p. 267.↩

3. William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, in The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman, rev. ed. (New York: Anchor Books, [1965] 1988), p. 35; pl. 6.↩

4. Peter A. Schock, Romantic Satanism: Myth and the Historical Moment in Blake, Shelley, and Byron (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), p. 3.↩

5. Lord Byron, quoted in Jerome J. McGann, Don Juan in Context (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976), p. 25; Percy Bysshe Shelley, Preface to Prometheus Unbound (1820), in Shelley’s Poetry and Prose, ed. Donald H. Reiman and Neil Fraistat (New York [2d rev. ed. 1977]: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2002), p. 207.↩