The War in Heaven has proven to be one of the most fascinating tales in the history of Christendom. The story of Lucifer’s celestial revolt has been told many times over, not least by Milton in Book VI of Paradise Lost (1667), a remarkably unique interpretation involving a three-day conflict that sees Heaven war-torn by cannon fire and mountain-hurling, which requires the Son of God—God the Father’s “Second Omnipotence” (VI.684)—to enter the conflict and rout the rebel angels out of Heaven. As surprising as it may be, the familiar story of the heavenly rebellion of the preeminent angelic prince Lucifer is not strictly biblical; indeed, little of what is now common knowledge about the Devil has a solid biblical basis. The Miltonic Satan we all know and the Romantics loved was the product of a lengthy evolution of the Devil’s biography within theology and literature.

Thumbing through the Bible in the hope of finding Milton’s tightly woven narrative of a cosmic conflict between God and Satan will inevitably turn out a time-wasting disappointment. The Devil is an extremely minor biblical figure, his appearances rare, dialogue even rarer. Satan is Hebrew for “adversary,” and in the Hebrew Bible—otherwise known as the Old Testament—the term was not originally a name but denoted a function or a stance,1 assumed by a mere mortal (1 Samuel 29:42) or even an immortal angel of the Lord (Numbers 22:223). The Hebrew Bible’s most fleshed out depiction of adversity personified—Satan as a supernatural person—is found in the first two chapters of the Book of Job, wherein Satan appears in Heaven, but not as an insurrectionist; Satan appears instead among the angels of the Lord, carrying out the role of divinely appointed tester, vetting the faith of God’s human servants,4 as in Zechariah (3:1–25). The Satan of the Old Testament, inasmuch as he exists at all, is an extremely hazy figure, and remarkably miniscule in comparison to Jehovah, who, for good or for ill, indisputably rules the world: “I form the light, and create darkness: I make peace, and create evil: I the LORD do all these things” (Isaiah 45:7).6

In the New Testament, though its diabology at times hearkens back to the Old Testament use of Satan in its semantic sense of “adversary” (see Mark 8:33; John 6:70–71)—Satan arguably even representative of collective Jewry,7 not least for Jesus effectively Satanizing the nonbelieving Jews (John 8:42–45)—the Devil of Christian Scripture is certainly a much more developed character. The New Testament Satan is presented as a formidable foe, “the prince of the power of the air, the spirit that now worketh in the children of disobedience…” (Ephesians 2:2). Although direct references to the Devil are sparse even in the New Testament, Satan is clearly portrayed as a cosmic bogeyman to be feared by all and at every step: “Be sober, be vigilant; because your adversary the devil, as a roaring lion, walketh about, seeking whom he may devour…” (1 Peter 5:8); “Put on the whole armour of God, that ye may be able to stand against the wiles of the devil” (Ephesians 6:11).

Satan’s heightened cosmic status in the New Testament was inherited from the apocryphal writings of the Intertestamental Period—the gap between the composition of the Old Testament and New Testament events—when the concept of a genuine Adversary against God began to blossom. The apocryphal books Enoch and Jubilees depict an angelic rebellion—or transgression, at least—incited by earthly desire, these fantastical texts about so-called “Watcher” angels copulating with mortal women and producing a hybrid race of “Nephilim” taking their inspiration from the sixth chapter of the Book of Genesis. These non-canonical stories lent themselves to the burgeoning biography of the Christian Satan,8 and the influence of the Intertestamental Period legends is evident throughout the New Testament: “…God spared not the angels that sinned, but cast them down to hell, and delivered them into chains of darkness, to be reserved unto judgment…” (2 Peter 2:4); “…the angels which kept not their first estate, but left their own habitation, he hath reserved in everlasting chains under darkness unto the judgment of that great day” (Jude 1:6). When Judgment Day is envisioned in the Gospel of Matthew, it is foreseen that the Son of God “shall set the sheep on his right hand, but the goats on the left,” and once the Son has parted the righteous sheep and the ungodly goats, “Then shall he say also unto them on the left hand, Depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire, prepared for the devil and his angels” (Matthew 25:33–41).9 Unlike the imprisoned Watchers of Enoch and Jubilees, however, demons abound in the New Testament world, and demonic possession is so widespread in the Scriptures10 that Jesus not only performs exorcisms himself (Mark 5:1–20; Luke 8:27–39), but empowers his disciples to deal with the world’s demonic infestation, in fact ordering them to exorcize demons as part of their public ministry (Matthew 10:1, 8).

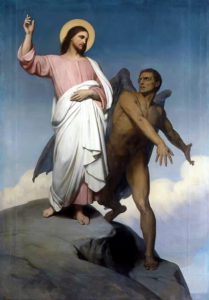

Satan “is decidedly not peripheral to the New Testament message,” explains Jeffrey Burton Russell, author of a five-volume investigation of the Devil in history and literature. “The saving mission of Christ can be understood only in terms of its opposition to the power of the Devil: that is the whole point of the New Testament.”11 Indeed, Christian Scripture is unequivocal on this point: “He that committeth sin is of the devil; for the devil sinneth from the beginning. For this purpose the Son of God was manifested, that he might destroy the works of the devil” (1 John 3:8). It was in the most elaborate Scriptural depiction of the opposition between Christ and the Devil that the New Testament Satan was fully fleshed out. By the fourth chapter of the first New Testament Gospel,12 the Devil is introduced into the narrative of Jesus, Satan carrying out three temptations of the Son of God in the wilderness (Matthew 4:1–11). The story serves to both make the Son look good and instruct believers in how to properly face temptation, as the Son easily dismisses Satan’s temptations by appealing to Scripture, his refrain: “it is written…” However, this story—repeated in two other Gospels (Mark 1:12–13; Luke 4:1–13) and retold by Milton in Paradise Regained (1671)—is also demonstrative of the heightened cosmic status of Satan. Unlike the Book of Job, wherein Satan is the Adversary of Man while still a servant of the will of God, the Gospels depict a Satan at odds with God’s will, which the Devil attempts to subvert on Earth. The Christian Satan is, as Milton puts it in Paradise Lost, “the Adversary of God and Man” (II.629).

What’s more, if in the Old Testament Satan is portrayed as somewhat presumptuous in the overzealous manner in which he carries out his God-given role of testing mortal faith—“And the LORD said unto Satan…thou movedst me against [Job], to destroy him without cause” (Job 2:3); “The LORD rebuke thee, O Satan…is not this [Joshua] a brand plucked out of the fire?” (Zechariah 3:1–2)—in the New Testament Satan is granted true hauteur in his independent attempt at tempting God Himself, incarnate as the Son of God. Also, in the Gospels Christ is tempted by a Devil wielding staggeringly greater power than that of the Hebrew Bible’s Satan: whereas Satan in the Old Testament merely prowls the Earth (Job 1:7; 2:2), in the New Testament Satan is shown in full possession of the planet, for when he shows the Son “all the kingdoms of the world, and the glory of them” (Matthew 4:8), Satan points out that these glorious kingdoms are at his disposal: “All this power will I give thee, and the glory of them: for that is delivered unto me; and to whomsoever I will I give it. If thou therefore wilt worship me, all shall be thine” (Luke 4:6–7; cf. Matthew 4:8–9).

The Devil’s dominance over the world is undisputed in the New Testament. “My kingdom is not of this world” (John 18:36), states Jesus, who himself concedes that it is Satan who is “the prince of this world” (John 12:31). Satan is elsewhere referred to as “the god of this world” (2 Corinthians 4:4) in Christian Scripture, which places all worldliness under the Devil’s aegis: “Love not the world, neither the things that are in the world. If any man love the world, the love of the Father is not in him. For all that is in the world, the lust of the flesh, and the lust of the eyes, and the pride of life, is not of the Father, but is of the world” (1 John 2:15–16). While the New Testament Satan is provided with such worldly preeminence, however, he is still a rather mysterious figure—still but a skeletal outline of the Devil that would be developed by Christian tradition, initially over the course of the first centuries of the Church. Satan’s official biography was the product of the early Church Fathers—namely the second-/third-century patristic writers Origen and Tertullian—who were truly responsible for formulating Satan’s story,13 a process consisting of a great deal of reading between the lines.

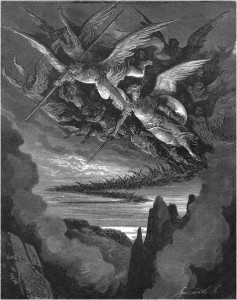

The New Testament’s most significant contribution to this Christian biography of Satan—certainly as far as Milton’s Paradise Lost is concerned—was to be found in the Book of Revelation, a cryptic text14 which liberally employs imagery befitting a bizarre fever dream. Revelation, which was very nearly left out of the official New Testament canon,15 envisions Satan inciting a War in Heaven:

And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven. And the great dragon was cast out, that old serpent, called the Devil, and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him. (Revelation 12:7–9)

Some patristic commentators, and later Luther, interpreted Revelation 12 as an allegory of the early Church, and Michael—a Hebrew name meaning “he who is like God”—as Christ,16 but the prevailing interpretation was that of a literal outbreak of angelic warfare in Heaven, a cataclysmic event predating the Fall in the Garden of Eden. This epic celestial conflict was even thought to have been glimpsed by Jesus, who remarked to his disciples, “I beheld Satan as lightning fall from heaven” (Luke 10:18).17

John of Patmos, the author of Revelation, himself anticipated patristic reinterpretations of biblical texts in equating “the great dragon” he writes of with “that old serpent, called the Devil, and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world…” (Revelation 12:9).18 Previously, the double-talking villain of the Garden of Eden was understood to be a mere serpent, but Christian tradition recast the slimy tempter as a serpentine Satan—or a serpent demonically possessed by Satan, as in Paradise Lost (IX.182–91). The reconceived Eden serpent was the Devil in disguise, who deceives Adam and Eve into forfeiting dominion over the world through their original sin against the Deity. In addition to Satan, the Son of God was also spotted in Eden, the cosmic feud between the two supposedly foretold in the curse God places upon the serpent: “And I will put enmity between thee and the woman, and between thy seed and her seed; it shall bruise thy head, and thou shalt bruise his heel” (Genesis 3:15).19

Confident that the Christian Satan, whose official biography was being gradually pieced together, was to be found hidden in the Hebrew Bible, the Church Fathers curiously identified sightings of Satan’s heavenly insurrection in two Old Testament accounts of the fall of earthly tyrants brought low by their hubris: Isaiah 14 and Ezekiel 28.20 “How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning!” thunders the biblical prophet Isaiah,

How art thou cut down to the ground, which didst weaken the nations! For thou hast said in thine heart, I will ascend into heaven, I will exalt my throne above the stars of God: I will sit also upon the mount of the congregation, in the sides of the north: I will ascend above the heights of the clouds; I will be like the most High. Yet thou shalt be brought down to hell, to the sides of the pit. (Isaiah 14:12–15)

Isaiah’s diatribe is directed against the Babylonian tyrant Nebuchadnezzar, and in its context is clearly referring to “the king of Babylon” (Isaiah 14:4), whose fall will serve as a cautionary tale against overreaching ambition: “They that see thee shall narrowly look upon thee, and consider thee, saying, Is this the man that made the earth to tremble, that did shake kingdoms; That made the world as a wilderness, and destroyed the cities thereof; that opened not the house of his prisoners?” (Isaiah 14:16–17). The extravagant imagery employed by Isaiah to overstress the overriding pride and commensurate downfall of this tyrant led the Fathers of the Christian Church to conclude that the king himself, rather than the vivid language used to describe his spectacular fall from the seat of power, was figurative—a means to describe the Devil’s fall from grace, and Ezekiel 28:12–19 would be absorbed into the Devil’s biography for the same reasons. For the Church Fathers, Isaiah’s diatribe revealed that Satan became Satan because he in his unbounded pride aspired above his station, Lucifer the angelic rebel having established himself as simia Dei,21 arrogating divine attributes in his ambition to “be like the most High” (Isaiah 14:14), just as he would later tempt Eve and Adam to “be as gods” (Genesis 3:5), thereby mirroring his own sin and suffering like exile from Paradise.

Lucifer, as invoked in Isaiah 14:12, is Latin for “light-bearer,” and the original Hebrew reads Helel ben Shahar, “Day Star, son of the Dawn.” It is a reference to Venus, the Morning Star, which is the “light-bringer,” appearing to herald the light of the rising Sun. “Day Star” transitioned into “Lucifer” in Latin translations of the Bible, such as St. Jerome’s fourth-century Latin Vulgate Bible. The continued use of Lucifer as a proper name contributed a significant element to the traditional biography of Satan: before falling from Heaven and becoming Satan, “the Adversary,” the Devil possessed the name Lucifer, which signified the great celestial status he once possessed and forever lost.22

Proud Lucifer’s fall from Heaven would serve as a timeless tale demonstrating the biblical aphorism “Pride goeth before destruction, and an haughty spirit before a fall” (Proverbs 16:18). Recreations of Lucifer’s heavenly rebellion on the medieval stage imagined an egomaniacally evil angel, who in a moment of impulsive pride seats himself on the vacant Throne of God and commands the angelic host to adore him, before long instantaneously and ignominiously transported to Hell by the Almighty Himself.23 Fallen from Heaven, the Devil of the Middle Ages was depicted as a hideous creature, and the greatest of these deformed Devils was Dante’s Lucifer, who in the Inferno of the Divine Comedy (1308–21) lies in the ninth and lowest circle of Hell as a gigantic, hairy, three-faced monstrosity frozen below the waist in unbreakable ice (XXXIV.28–67). Dante’s use of the name “Lucifer” is an ironic mockery of the perfidious angelic prince, who “was once as handsome as he now / is ugly,” imprisoned in the icy depths of the treacherous circle of Hell because he “raised his brows / against his Maker” (XXXIV.34–36).

Medievalism’s visual vilifications of Satan carried over into Renaissance art,24 but there were a number of Renaissance literary works which conceded a certain degree of proto-Miltonic majesty in their treatments of Lucifer’s heavenly revolt. Indeed, Stella Purce Revard, in her study of The War in Heaven: Paradise Lost and the Tradition of Satan’s Rebellion, posits that Milton’s epic hero Satan is an installment in a long line of Renaissance Lucifers.25 There are certainly similarities between the Renaissance Devils and Milton’s epic hero Satan, the “great Commander” (I.358) of the “Satanic Host” (VI.392), not least that in these Renaissance works “pride and ambition, long identified as Lucifer’s sins, acquire specific political ramifications.”26 What’s more, these Renaissance depictions of the Devil would invest the character with a complexity which, as Revard observes, is decidedly different from “a motiveless malignancy (which patristic tradition gives us) or a strutting egotist (which the medieval mysteries pose).”27 Indeed, many of these Renaissance rebel angels vocalize the virtue, valor, nobility, and glory of their war with God.28 It was Milton, however, who most infused Satan’s rebellion with evocative political overtones, which was due in no small part to the antimonarchical and regicide-defending Milton’s own extensive experience in the political realm.

In Paradise Lost, Satan lambasts God as a “Tyrant” (X.466), and the archangel’s “ambitious aim / Against the Throne and Monarchy of God” (I.41–42) is saturated with republican sentiment. His rebellion set in motion by God the Father’s exaltation of His Son to cosmic kingship (V.600–15, 657–71), Milton’s Satan asserts himself as the “Antagonist of Heav’n’s Almighty King” (X.387), and it is with great “disdain” that Milton’s archangelic arch-rebel decides “With all his Legions to dislodge, and leave / Unworshipt, unobey’d the Throne supreme, / Contemptuous…” (V.566, 569–71). Protesting that the newly crowned Son “hath to himself ingross’t / All Power, and us eclipst under the name / Of King anointed” (V.775–77), Satan scorns “Knee-tribute” as “prostration vile” (V.782) before the angels beneath his banner, asking,

Who can in reason then or right assume

Monarchy over such as live by right

His equals, if in power and splendor less,

In freedom equal? (V.794–97)

Milton’s Satan incites rebellion among his angels by urging them “to cast off this Yoke” of the Messiah, ordained by God “to be our Lord, / And look[s] for adoration…” (V.786, 799–800).

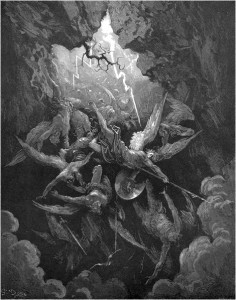

Paradise Lost follows in the tradition of its Renaissance precursors insofar as it awards the rebel angel with not only a sense of a just cause but great majesty and epic heroism in his pursuit of it as well: when “The banded Powers of Satan” (VI.85) appear on the heavenly battlefield, intent “To win the Mount of God, and on his Throne / To set the envier of his State, the proud / Aspirer” (VI.88–90), Satan appears in boundless majesty:

High in the midst exalted as a God

Th’ Apostate in his Sun-bright Chariot sat

Idol of Majesty Divine, enclos’d

With Flaming Cherubim, and golden Shields;

Then lighted from his gorgeous Throne.…

Satan with vast and haughty strides advanc’d,

Came tow’ring, arm’d in Adamant and Gold… (VI.99–110)

Yet Milton goes much farther than his Renaissance forebears by making his fallen archangel incomparably magnificent in Hell, where the reader first encounters him at the start of Paradise Lost. Satan the heavenly rebel angel is described as “Sun-bright” (VI.100), and yet Satan the hellish fallen angel—the so-called “Prince of Darkness” (X.383)—is still likened to the Sun, though as obscured by a misty horizon or eclipsed by the Moon (I.592–99). In short, Milton’s Satan remains in possession of a considerable degree of his “Original brightness” (I.592), as does the fallen rebel host, likened by Milton to a lightning-scorched but nonetheless stately forest (I.612–15). The ruined rebel angels, despite their diminished glory, bear “Godlike shapes and forms / Excelling human, Princely Dignities” (I.358–59), and no one is as princely and godlike as Satan himself, who “above the rest / In shape and gesture proudly eminent / Stood like a Tow’r” (I.589–91), his preeminence signified by his surprising resplendence: “Dark’n’d so, yet shone / Above them all th’ Arch-Angel…” (I.599–600). The prior Renaissance treatments of Satan’s revolt all upheld the medieval tradition of marring the fallen angel’s marvelous face and form,29 and were therefore far more unforgiving when visualizing Satan’s infernal fall than Milton, whose fallen angel cuts a truly dazzling figure.

The Satan of Paradise Lost bears “Brows / Of dauntless courage, and considerate Pride” (I.602–3) and a “mighty Stature” (I.222), and he is much reminiscent of classical heroes as he firmly grips his ponderous shield and mast-like spear (I.284–96). These heroic features are not merely superficial, moreover, for Milton’s Satan is at his most impressive not during the War in Heaven but when in Hell, where even in the midst of damnation he decries “the Tyranny of Heav’n” (I.124) and is found “Hurling defiance toward the Vault of Heav’n” (I.669). In the “Infernal Pit” (I.657), Milton’s Satan boasts of his “unconquerable Will” and “courage never to submit of yield” (I.106, 108), and he indeed exhibits such Promethean pride and endurance in the face of incredible loss and suffering—not unlike Milton himself throughout the Restoration, the oppressive period during which the then blind pariah of a poet composed Paradise Lost. Milton’s curiously sympathetic portrait of the fallen archangel was genuinely unprecedented, and it was quite a godsend that, as Jeffrey Burton Russell notes, Milton’s was “a scenario so coherent and compelling that it became the standard account for all succeeding generations.”30 Paradise Lost was designed as a Christian epic poem meant to “justify the ways of God to men” (I.26), but as Percy Bysshe Shelley aptly put it in his unpublished Essay on the Devil and Devils (ca. 1819–20), “the Devil…owes everything to Milton.”31

An interpretation of Milton’s War in Heaven was nearly brought to the silver screen about a half-decade back. The plug was pulled on the Paradise Lost film at the eleventh hour, however, and so until that project escapes from development hell—or until the recently proposed TV series comes to fruition—the most complete depiction of the War in Heaven belongs to Superbook, amusingly enough. Superbook is an animated series of religious stories made palatable for Christian kids, who are taken on a tour through biblical times with the two young protagonists and their zany robot friend as they make their way through episodes from “the Book.” Superbook’s original 1980s incarnation was an attempt by the Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN) to reach out to a Japanese audience, and the show, produced in Japan by Tatsunoko Productions under the name Anime Oyako Gekijō (Animated Parent and Child Theatre), was an immense success. The CBN launched a new Superbook series in 2011—when Legendary Pictures’ Paradise Lost film seemed like it was actually going to happen—and the show’s first episode, “In The Beginning,” focused on the fall of Lucifer and his subsequent temptation of Eve in the Garden of Eden. The impressionable youth watching Superbook are meant to learn the importance of obedience by beholding the rebel Lucifer’s cataclysmic loss, the result of his having “thought he could be like God.” This is not dissimilar to the message conveyed by Milton, who speaks to the reader through Raphael when the archangel, in his education of Adam and Eve, concludes the story of the War in Heaven with the following words of warning:

…let it profit thee to have heard

By terrible Example the reward

Of disobedience; firm they might have stood,

Yet fell; remember, and fear to transgress. (VI.909–12)

Yet of course Milton’s Adam, also like the reader, is rather thrilled when he first learns that “some are fall’n, to disobedience fall’n, / And so from Heav’n to deepest Hell” (V.541–42), the first man absolutely fascinated by the story of the War in Heaven (V.544–60). Also, the angel Abdiel—the sole seditionist among the rebel angels (V.803ff.)—is shocked and horrified when he sees the still-heavenly radiant Satan appear on the battlefield: “O Heav’n! that such resemblance of the Highest / Should yet remain, where faith and realty / Remain not…” (VI.114–16). The Lucifer of Superbook is not Miltonic per se, and Superbook’s retelling of this timeless tale by no stretch of the imagination matches up to Milton’s, but it is not difficult to imagine the show’s visualization of the warring rebel angel inciting reactions similar to those of Milton’s Adam and Abdiel in its young viewership.

Superbook’s Satan is both “motiveless malignancy” and “strutting egotist,” to borrow Revard’s terms. While his dialogue is unsurprisingly nothing special—best described as biblical verse filtered through a Disney villain (“I am God’s greatest work, and I shall ascend above all of Creation!”)—this Lucifer is nevertheless rather impressive in terms of appearance: a bright-eyed, blond-haired, full-armored figure with two sets of massive, luminous angel wings. The image of Lucifer rousing his rebel army, who cheer him on and wave their arms as he directs his steely gaze toward the Kingdom of Heaven in the distance, his long locks of hair swept by the wind, is rather stirring. What’s more, like Milton’s Satan, “who that day / Prodigious power had shown, and met in Arms / No equal” (VI.246–48), the aspiring angel of Superbook holds his own in combat, eliminating a number of angelic combatants in a sulfurous whirlwind attack. Unlike Paradise Lost, wherein the Son of God is required to overcome the resilient rebel army on the third day, Superbook is more traditional inasmuch as it has Lucifer defeated by Michael after a rather short-lived celestial conflict. (Milton does have the archangel Michael best Satan in battle on the first day of the war, but ultimately only omnipotence can overcome the rebel angel and his host).

Superbook’s Satan is both “motiveless malignancy” and “strutting egotist,” to borrow Revard’s terms. While his dialogue is unsurprisingly nothing special—best described as biblical verse filtered through a Disney villain (“I am God’s greatest work, and I shall ascend above all of Creation!”)—this Lucifer is nevertheless rather impressive in terms of appearance: a bright-eyed, blond-haired, full-armored figure with two sets of massive, luminous angel wings. The image of Lucifer rousing his rebel army, who cheer him on and wave their arms as he directs his steely gaze toward the Kingdom of Heaven in the distance, his long locks of hair swept by the wind, is rather stirring. What’s more, like Milton’s Satan, “who that day / Prodigious power had shown, and met in Arms / No equal” (VI.246–48), the aspiring angel of Superbook holds his own in combat, eliminating a number of angelic combatants in a sulfurous whirlwind attack. Unlike Paradise Lost, wherein the Son of God is required to overcome the resilient rebel army on the third day, Superbook is more traditional inasmuch as it has Lucifer defeated by Michael after a rather short-lived celestial conflict. (Milton does have the archangel Michael best Satan in battle on the first day of the war, but ultimately only omnipotence can overcome the rebel angel and his host).

More significantly, whereas in Paradise Lost the fallen archangel’s “form had yet not lost / All her Original brightness, nor appear’d / Less than Arch-Angel ruin’d” (I.591–93), Superbook instead follows tradition by having Satan transform into a monstrous figure as he falls from Heaven—with the horns, talons, and tail Milton had graciously discarded. (Superbook does however permit the fallen angel to assume his former angelic form—a literal interpretation of the biblical warning that the ever deceitful Devil is capable of “transform[ing] into an angel of light” [2 Corinthians 11:14], which was also Milton’s inspiration for having Satan transform into a “stripling Cherub” [III.636] in order to deceive the archangel Uriel in their encounter on the Sun [III.654ff.].) In any event, as laughably cheesy as Superbook may be, its rather surprising depiction of Lucifer in the War in Heaven is noteworthy, not least for being more impressive than how Milton’s Satan was imagined in the concept art for the Paradise Lost film—especially Satan’s fallen form, which apparently would have been even more monstrous than that of the Satan of Superbook.

More significantly, whereas in Paradise Lost the fallen archangel’s “form had yet not lost / All her Original brightness, nor appear’d / Less than Arch-Angel ruin’d” (I.591–93), Superbook instead follows tradition by having Satan transform into a monstrous figure as he falls from Heaven—with the horns, talons, and tail Milton had graciously discarded. (Superbook does however permit the fallen angel to assume his former angelic form—a literal interpretation of the biblical warning that the ever deceitful Devil is capable of “transform[ing] into an angel of light” [2 Corinthians 11:14], which was also Milton’s inspiration for having Satan transform into a “stripling Cherub” [III.636] in order to deceive the archangel Uriel in their encounter on the Sun [III.654ff.].) In any event, as laughably cheesy as Superbook may be, its rather surprising depiction of Lucifer in the War in Heaven is noteworthy, not least for being more impressive than how Milton’s Satan was imagined in the concept art for the Paradise Lost film—especially Satan’s fallen form, which apparently would have been even more monstrous than that of the Satan of Superbook.

That the War in Heaven has been one of the most fixating stories in the history of Christianity and the cartoonish Superbook offers up its only real full-fledged depiction in modern media highlights just how needed an adaptation of Milton’s Paradise Lost is. While Satan has been beloved by cinema since its inception, motion pictures have hitherto offered but mere glimpses of celestial conflict,32 more often than not resorting to the much cheaper option of the Devil-as-tempter. (D.W. Griffith’s The Sorrows of Satan [1926] included both the martial rebel angel and the sleek tempter in human form, but the former, which was featured in the film’s prologue, was ultimately left on the cutting room floor.) The War in Heaven is the most cinematic story in Lucifer’s biography, and it is definitely time for the modern day’s most audacious visual medium to give the Devil his due: the regal rebel angel’s defining moment of heroic heavenly revolt.

Notes

1. See Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, [1977] 1987), pp. 189–90; Satan: The Early Christian Tradition (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, [1981] 1987), pp. 25, 27; Neil Forsyth, The Old Enemy: Satan and the Combat Myth (Princeton: Princeton University Press, [1987] 1989), p. 113; Henry Ansgar Kelly, Satan: A Biography (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), pp. 2–3.↩

2. See T. J. Wray and Gregory Mobley, The Birth of Satan: Tracing the Devil’s Biblical Roots (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), p. 53; Kelly, p. 17.↩

3. See Forsyth, The Old Enemy, p. 113; Wray and Mobley, pp. 57–58; Kelly, pp. 14–17.↩

4. See Russell, The Devil, pp. 198–204; Forsyth, The Old Enemy, pp. 110–11, 114; Wray and Mobley, pp. 58–64; Kelly, pp. 21–23, 27, 168–69, 175.↩

5. See Forsyth, The Old Enemy, pp. 115–18; Wray and Mobley, pp. 64–66; Kelly, pp. 23–25.↩

6. See Russell, The Devil, pp. 174–83; Forsyth, The Old Enemy, pp. 107–09; Peter Stanford, The Devil: A Biography (New York: Henry Holt and Company, Inc., 1996), pp. 36–40.↩

7. See Elaine Pagels, The Origin of Satan (New York: Vintage Books, [1995] 1996), p. 101. In John’s Gospel, Pagels points out, the Jews perform the temptations of Jesus ascribed to Satan in Mark, Matthew, and Luke. Mark’s Gospel vaguely mentions Jesus being “tempted of Satan” (Mark 1:13) in the wilderness, but Matthew and Luke expand upon Mark’s account and portray the Satanic temptations of the Son of God, the most significant of which is Satan’s offer of power over all the kingdoms of the world (Matthew 4:8–9; Luke 4:5–6). In John’s Gospel, however, Jesus refuses this “offer” of worldly power not from Satan but from Jews impressed by his miraculous power: “When Jesus therefore perceived that they would come and take him by force, to make him a king, he departed again into a mountain himself alone” (John 6:15). Similarly, just as the first of Satan’s triad of temptations of Jesus is to turn stones into bread to verify that he truly “be the Son of God” (Matthew 4:3; Luke 4:3), in John’s Gospel it is the Jews who question Jesus along these lines: “They said therefore unto him, What sign shewest thou then, that we may see, and believe thee? what dost thou work? Our fathers did eat manna in the desert; as it is written, He gave them bread from heaven to eat” (John 6:30–31). Jesus’ response is essentially the same he delivers to Satan in Matthew 4:4 and Luke 4:4: “Then Jesus said unto them, Verily, verily, I say unto you, Moses gave you not that bread from heaven; but my Father giveth you the true bread from heaven. For the bread of God is he which cometh down from heaven, and giveth life unto the world” (John 6:32–33).

↩

8. See Russell, The Devil, pp. 191–94; Stella Purce Revard, The War in Heaven: Paradise Lost and the Tradition of Satan’s Rebellion (Ithaca, NY and London: Cornell University Press, 1980), pp. 29–32; Wray and Mobley, pp. 99–105; Kelly, pp. 32–41.↩

9. In Matthew 25:41—as in other biblical passages, such as “A wise man’s heart is at his right hand; but a fool’s heart at his left” (Ecclesiastes 10:2), and “let not thy left hand know what thy right hand doeth” (Matthew 6:3)—the Bible openly expresses a right-handed bias. Abnormal left-handedness has throughout human history been viewed as suspect—or sinister, Latin for “left.” In Milton’s Paradise Lost, Sin is born full-grown from the sinister side of Satan’s head (II.752–58), and Eve is formed from a rib taken from Adam’s sinister side (VIII.460–71). Milton’s Adam comments on this after the Fall, complaining that his wayward wife is “but a Rib / Crooked by nature, bent, as now appears, / More to the part sinister from me drawn” (X.884–86).↩

10. Ailments such as deafness, dumbness, and blindness are said to be caused by “unclean spirits” in the New Testament (Mark 6:7; Luke 11:14, 13:10–13), whereas in the Old Testament Jehovah had claimed responsibility for these afflictions (Exodus 4:11).↩

11. Russell, The Devil, p. 249.↩

12. Mark’s was actually the first Gospel written, though Matthew’s Gospel has been placed first.↩

13. Origen’s belief in the ultimate salvation of Satan was, however, not to take hold in the tradition. See Russell, Satan, pp. 144–48; The Prince of Darkness: Radical Evil and the Power of Good in History (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, [1988] 1992), p. 81.↩

14. Revelation is fairly straightforward about its allegorical nature: “…I saw seven golden candlesticks; And in the midst of the seven candlesticks one like unto the Son of man.…And he had in his right hand seven stars.…The mystery of the seven stars which thou sawest in my right hand, and the seven golden candlesticks. The seven stars are the angels of the seven churches: and the seven candlesticks which thou sawest are the seven churches” (1:12–13, 16, 20).↩

15. See Jonathan Kirsch, A History of the End of the World: How the Most Controversial Book of the Bible Changed the Course of Western Civilization (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, [2006] 2007), pp. 112–16.↩

16. See Revard, pp. 109–10.↩

17. Luke 10:18, when read in context, appears to refer to a future fall of the Devil. In Luke’s Gospel, the seventy disciples of Jesus return to joyously report, “Lord, even the devils are subject unto us through thy name,” and in his response, Jesus appears to express assurance that the miraculous efficacy he has bestowed upon them portends the inevitable overthrow of Satan’s reign over the earth, which will be a lightning-speed plummet from power: “And he said unto them, I beheld Satan as lightning fall from heaven. Behold, I give unto you power to tread on serpents and scorpions, and over all the power of the enemy: and nothing shall by any means hurt you” (Luke 10:17–19). See Forsyth, The Old Enemy, pp. 294–95; Kelly, pp. 97–100.↩

18. John may have been referring to “Leviathan,” the Old Testament’s “piercing…crooked serpent…the dragon that is in the sea” (Isaiah 27:1), also described as “a king over all the children of pride” (Job 41:34). The connection between the dragon of Revelation 12 and the serpent of Geneses 3 was nonetheless solidified by second-century Christian theologian Justin Martyr. See Russell, The Prince of Darkness, pp. 62–63; Kelly, pp. 151–52.↩

19. Despite being referenced after the death of Jesus—“the God of peace shall bruise Satan under your feet shortly” (Romans16:20)—the Genesis 3 passage known within Christian theology as the “protevangelium” anticipates the virgin birth of Jesus by Mary (the “woman’s seed”) and the Passion, which will paradoxically be Satan’s undoing (“it shall bruise thy head, and thou shalt bruise his heel”). See Forsyth, The Old Enemy, pp. 271–72.↩

20. See Russell, The Devil, pp. 195–97; Satan, pp. 130–33; The Prince of Darkness, pp. 78–80; Revard, pp. 32–35, 47–49; Forsyth, The Old Enemy, pp. 134–39, 370–71; The Satanic Epic (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), pp. 44–45, 51–54, 80–81; Luther Link, The Devil: A Mask without a Face (London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 1995), pp. 22–27; Wray and Mobley, pp. 108–12; Kelly, pp. 191–99.↩

21. See Maximilian Rudwin, The Devil in Legend and Literature (LaSalle, IL: Open Court Publishing Company, [1931] 1959), Ch. XII, “Diabolus Simia Dei,” pp. 120–29.↩

22. See Russell, The Devil, pp. 195–97; The Prince of Darkness, pp. 43–44; Forsyth, The Old Enemy, pp. 134–36; The Satanic Epic, pp. 51–54, 80–81; Link, pp. 22–23; Wray and Mobley, pp. 108–10.↩

23. See Revard, pp. 201–03; Russell, Lucifer, pp. 250–52.↩

24. For exceptions, see Roland Mushat Frye, “Milton’s Paradise Lost and the Visual Arts,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 120, No. 4, Symposium on John Milton (Aug. 13, 1976), pp. 233–44.↩

25. Revard, p. 198: “Satan, proud but magnificent, unyieldingly resolute in battle, emerges in the Renaissance poems wearing the full splendor of epic trappings. To these poems we owe in large measure the hero Satan as he is developed in Paradise Lost. Renaissance poets drew on two traditions to depict Satan or Lucifer: the hexaemeral and the epic. Hexaemera described Lucifer as a prince, glorious and unsurpassed, whose ambition caused him to strive above his sphere; epics described their heroes as superhuman in battle and accorded them, whatever their arrogance or mistakes in judgment, ‘grace’ to offend, even as they are called to account for their offenses. The Lucifer of the Renaissance thus combines Isaiah’s Lucifer with Homer’s Agamemnon, Virgil’s Turnus, and Tasso’s Rinaldo. Milton’s Satan, in turn, follows the Renaissance Lucifer and is both the prince depicted in hexaemera and the classical battle hero.”↩

26. Ibid., pp. 200–01.↩

27. Ibid., p. 210.↩

28. See Watson Kirkconnell, The Celestial Cycle: The Theme of Paradise Lost in World Literature with Translations of the Major Analogues (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1952), pp. 61–62 (Torquato Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberate, 1581); 237–38 (Giambattista Andreini’s L’Adamo, 1613); 276 (Phineas Fletcher’s The Locusts, or Apollyonists, 1627); 351 (Joseph Beaumont’s Psyche, or Love’s Majesty, 1648); 360 (Jacobus Masenius’ Sarcotis, 1654); 372, 401, 403, 405 (Joost van den Vondel’s Lucifer, 1654); 422 (Abraham Cowley’s Davideis, 1656); 431 (Samuel Pordage’s Mundorum Explicato, 1661).↩

29. See ibid., pp. 59–61 (Torquato Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberate, 1581); 221 (Giambattista Marini’s La Strage degli Innocenti, 1610); 236 (Giambattista Andreini’s L’Adamo, 1613); 350–51 (Joseph Beaumont’s Psyche, or Love’s Majesty, 1648); 414–15 (Joost van den Vondel’s Lucifer, 1654).↩

30. Jeffrey Burton Russell, Mephistopheles: The Devil in the Modern World (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, [1986] 1990), p. 95.↩

31. Percy Bysshe Shelley, Essay on the Devil and Devils, in Shelley’s Prose: or the Trumpet of a Prophecy, ed. David Lee Clark, pref. Harold Bloom (New York: New Amsterdam Books, 1988), p. 268.↩

32. For a comprehensive catalogue of heavenly conflict in cinema, see Eric C. Brown, Milton on Film (Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press, 2015), Ch. 5, “Winged Warriors and the War in Heaven,” pp. 245–81.↩