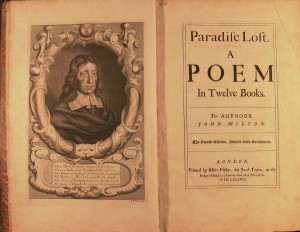

The Devil “owes everything to Milton,” observed Percy Bysshe Shelley, as “Milton divested him of a sting, hoofs, and horns, clothed him with the sublime grandeur of a graceful but tremendous spirit—and restored him to the society.”1 Shelley—who, alongside Lord Byron, was implicated in “the Satanic School” of Romanticism—was quite right to point out that Milton’s radical epic portrait of Satan in Paradise Lost (1667) lent itself to the Romantic reappraisal of the arch-rebel in the poetry, prose, and visual arts of the era.

Visualizations of Paradise Lost are a powerful form of commentary on the poem, and one cannot overstress the significance of Romantic illustrations of Milton’s Satan. “The critical power and influence of the illustrator is exceedingly great,” notes Stephen C. Behrendt, “perhaps greater even than that of the verbal critic…”2 It would certainly be unwise to underestimate the importance of literary illustration, and Romanticism’s idealized renderings of Milton’s Satan are in fact the closest approximations of Milton’s grand poetic descriptions of the Devil.

The very first illustrations for Paradise Lost, produced in 1688 by Henry Aldrich, Bernard Lens, and John Baptist Medina,3 failed to adequately represent Milton’s Satan. In the illustrations for Book I and Book II, though Satan dons a Roman tunic and brandishes a spear, his looks otherwise commingle the bestial and buffoonish Devil of the Middle Ages: tiny wings, the ears of an ass, and, protruding through snaky locks of hair, horns. Even more deformed is the Satan illustrated for Book III, a nude figure with clawed feet, furry thighs, and a tail. In the illustration for Book IX, Milton’s Satan is reduced to the stereotypical medieval Devil, cloven hooves and all. This is not by any means the Satan of Milton’s Paradise Lost, the “great Commander” (I.358) who, firmly gripping shield and spear (I.284–96), dons the splendid trappings of classical epic heroes.

Traditionally, the Devil became deformed in his descent from Heaven into Hell, but Milton broke radically from tradition and portrayed the fallen angel as a truly majestic figure. The only trace of genuine deformity in Milton’s Satan is that “his face / Deep scars of Thunder had intrencht” (I.600–01). Yet these battle scars—like his massive shield’s resemblance to the spotty Moon (I.284–91) or his own resemblance to “a weather-beaten Vessel” with “Shrouds and Tackle torn” (II.1043–44) as he boldly ventures through Chaos on “indefatigable wings” (II.408)—only serve to make Satan seem more heroic; the thunder-scarred visage of Milton’s Satan merely magnifies the impressiveness of his “Brows / Of dauntless courage, and considerate Pride” (I.602–3).

Milton’s Satan is in Heaven described as “of the first, / If not the first Arch-Angel, great in Power, / In favor and preëminence” (V.659–61), and his princely prestige is indicated by his splendor. The celestial radiance of “great Lucifer” (V.760) is likened to the star which lent him his prelapsarian name:

…great indeed

His name, and high was his degree in Heav’n;

His count’nance, as the Morning Star that guides

The starry flock… (V.706–09)

Heaven’s erstwhile Morningstar is ultimately outcast and reduced to “the Prince of Darkness” (X.383), but in Hell the “Arch-Angel ruin’d” (I.593) is not nearly as darkened as he might have been:

…his form had yet not lost

All her Original brightness, nor appear’d

Less than Arch-Angel ruin’d, and th’ excess

Of Glory obscur’d… (I.591–94)

In Heaven, “Th’ Apostate” is described as “Sun-bright” (VI.100), and in Hell “th’ Apostate Angel” (I.125) is still likened to the Sun, but as obscured by a misty horizon or eclipsed by the Moon (I.592–99). Milton’s dimmed Devil, in short, is the fallen Lucifer—“Dark’n’d so, yet shone / Above them all th’ Arch-Angel…” (I.599–600).

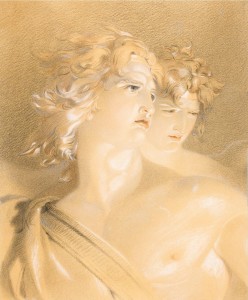

The Romantic Shelley did not say that the Devil “owes everything to us,” but rather that he “owes everything to Milton,” and indeed Milton’s Satan is portrayed with remarkable accuracy in the Romantic iconography of Thomas Stothard, Richard Corbould, James Barry, Richard Westall, Sir Thomas Lawrence, Henry Fuseli, William Blake, John Martin, and “the last of the Romantics,” Gustave Doré. Theirs was a truly handsome Devil, bringing to life Milton’s epic hero Satan, replete with an athletic physique, a passionate visage, and a proud mien. Romantic artists discarded the thitherto horned and hoofed Satan in exchange for a humanized and heroicized Lucifer, a paragon of classical beauty befitting the dazzling rebel who holds pride of place in Paradise Lost, the awe-inspiring artistic tradition of the Satanic sublime reaching its apex in Spanish sculptor Ricardo Bellver’s El Ángel Caído.

Commenting on the “long metamorphosis in the eighteenth century” of Milton’s Satan, when he was declared an exemplar of the sublime, Peter L. Thorslev, Jr. observes that “when he re-emerged in the romantic mind, he was no longer the (larval) serpent of the later books of Paradise Lost [IX.157–91, 412 ff.; X.504–77], but had reassumed his archangelic wings…”4 It is a beautiful metaphor, and Satan quite literally reassumed his wings in much of the Romantic iconography inspired by Milton’s epic poem. The fallen archangel’s metamorphosis was sometimes more radical still, for in the renditions of several prominent artists, such as Blake, Barry, Lawrence, and Fuseli, the classically beautiful fallen angel appears wingless, humanized to the extent of bearing a fully (idealized) human form. That Milton’s Satan was visualized as a Super-man rather than a Super-angel is in no small part indicative of the fact that, as Peter A. Schock observes in his study of Romantic Satanism, “the reimagined figure of Milton’s Satan embodied for the age the apotheosis of human desire and power.”5

Click here to see the Proto-Romantic Art.

Click here to see the Romantic Art.

Click here to see the Post-Romantic Art.

Notes

1. Percy Bysshe Shelley, Essay on the Devil and Devils (ca. 1819–20), in Shelley’s Prose: or the Trumpet of a Prophecy, ed. David Lee Clark, pref. Harold Bloom (New York: New Amsterdam Books, 1988), p. 268.↩

2. Stephen C. Behrendt, The Moment of Explosion: Blake and the Illustration of Milton (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1983), p. 91.↩

3. See ibid.↩

4. Peter L. Thorslev, Jr., “The Romantic Mind Is Its Own Place,” Comparative Literature, Vol. 15, No. 3 (Summer, 1963), pp. 251–52.↩

5. Peter A. Schock, Romantic Satanism: Myth and the Historical Moment in Blake, Shelley, and Byron (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), p. 3.↩