“Nature abhors a vacuum. If the Devil didn’t exist, we’d have to reinvent him.”1

— Holly Black, Lucifer #5

I was both enthused and apprehensive when it was announced at the 2015 San Diego Comic-Con that Vertigo would be bringing back Lucifer. On the one hand, I was enthused because, as I’ve written extensively about in my four-part “Why Vertigo’s Lucifer Morningstar Matters,” Lucifer presents modern popular culture—predominantly saturated with Satans of either the medievally monstrous or lightheartedly comical variety—with the Miltonic-Romantic Satan’s true heir, and this neo-Romantic rebel angel thus helps expand the reach and influence of the grand tradition wherefrom he derives. On the other hand, I was apprehensive because Mike Carey had not only executed but concluded his 75-issue Lucifer series so perfectly that I worried about his masterful treatment of the Morningstar being tampered with, especially in the hands of another writer. Yet I must say that Holly Black’s yearlong Lucifer run has been remarkably impressive, and I, who read Carey’s series religiously, applaud Black’s success in once more taking the Devil descended from the tradition of Milton and the Romantic Satanists and making the rebellious Morningstar a veritable star in modern popular culture.

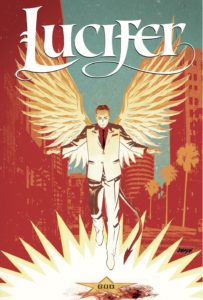

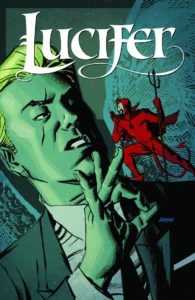

Apart from my general apprehensions about Lucifer being brought back nearly ten years after its perfect finish, I had two major concerns: the visual presentation of the titular angelic anti-hero and the plot. First off, while the Lucifer of Black’s comic was obviously far closer visually to the Lucifer of Carey’s than the Lucifer of Fox’s TV show (played by Tom Ellis), I was somewhat concerned when I saw the cover art for the first issue of the new Lucifer. My reaction was mixed: I was pleased to see that Lucifer retained his angelic wings, but alarmed when I saw that he had the barbed tail of a stereotypical demon; I was delighted to see that Lucifer kept the massive gash across his flawless face—given to him by his sole love Mazikeen as something to remember her by at the end of Carey’s series2—but I was disturbed by Lucifer looking like Scarface in an all-white suit. My worry continued as I made my way through the opening pages of Lucifer’s first issue, wherein the white-suited Lucifer pulls into Los Angeles in a white convertible, with the license plate “LC4R,” and enlists the dregs of society in the construction of Ex Lux, his new L.A. piano bar—here, like Lux in Lucifer on Fox, imagined as more of a nightclub. It all seemed too gaudy and cheesy for the refined rebel Mike Carey gave us. Fortunately, Black’s Lucifer swiftly sheds this skin, and even though his attire falls short of the dandified look Carey’s Lucifer adopts—Black’s Lucifer clothed rather like an Express model, in slim suits, skinny ties, and winkle pickers—the new Lucifer looks great.

Apart from my general apprehensions about Lucifer being brought back nearly ten years after its perfect finish, I had two major concerns: the visual presentation of the titular angelic anti-hero and the plot. First off, while the Lucifer of Black’s comic was obviously far closer visually to the Lucifer of Carey’s than the Lucifer of Fox’s TV show (played by Tom Ellis), I was somewhat concerned when I saw the cover art for the first issue of the new Lucifer. My reaction was mixed: I was pleased to see that Lucifer retained his angelic wings, but alarmed when I saw that he had the barbed tail of a stereotypical demon; I was delighted to see that Lucifer kept the massive gash across his flawless face—given to him by his sole love Mazikeen as something to remember her by at the end of Carey’s series2—but I was disturbed by Lucifer looking like Scarface in an all-white suit. My worry continued as I made my way through the opening pages of Lucifer’s first issue, wherein the white-suited Lucifer pulls into Los Angeles in a white convertible, with the license plate “LC4R,” and enlists the dregs of society in the construction of Ex Lux, his new L.A. piano bar—here, like Lux in Lucifer on Fox, imagined as more of a nightclub. It all seemed too gaudy and cheesy for the refined rebel Mike Carey gave us. Fortunately, Black’s Lucifer swiftly sheds this skin, and even though his attire falls short of the dandified look Carey’s Lucifer adopts—Black’s Lucifer clothed rather like an Express model, in slim suits, skinny ties, and winkle pickers—the new Lucifer looks great.

Lee Garbett has done a phenomenal job illustrating these new Lucifer comics over the past year, leaving each and every panel exceedingly polished. Following the lead of Carey’s Lucifer, illustrated by Peter Gross, Garbett renders the colorful otherworldly characters surrounding the fallen angel in either bestial or insectile guises, but keeps Lucifer himself a handsome Devil. There are slight differences, such as Lucifer bearing blue rather than golden eyes and his angelic wings always being exposed, but the point is that the fallen angel’s image is impressive, especially when he dons his battle armor, Lucifer appearing as though he just marched out of the Romantic artwork inspired by Milton’s Paradise Lost (namely Thomas Stothard’s).

Lee Garbett has done a phenomenal job illustrating these new Lucifer comics over the past year, leaving each and every panel exceedingly polished. Following the lead of Carey’s Lucifer, illustrated by Peter Gross, Garbett renders the colorful otherworldly characters surrounding the fallen angel in either bestial or insectile guises, but keeps Lucifer himself a handsome Devil. There are slight differences, such as Lucifer bearing blue rather than golden eyes and his angelic wings always being exposed, but the point is that the fallen angel’s image is impressive, especially when he dons his battle armor, Lucifer appearing as though he just marched out of the Romantic artwork inspired by Milton’s Paradise Lost (namely Thomas Stothard’s).

However Lucifer looked, there was of course the more significant issue of the plot he was to inhabit. I was frankly filled with trepidation when I learned that Holly Black’s Lucifer would consist of Lucifer, mysteriously wounded and fallen back to our world after a decade in the void he entered at the close of Carey’s comic, forced to work together with his disgraced angelic brother Gabriel to clear his name by solving the ultimate murder mystery: the death of God. (Yahweh, that is, not Elaine Belloc, who in Carey’s comic assumed the vacant Throne of God to keep Creation from crumbling.3) Lucifer’s resurrection was coinciding with the Vertigo series’ TV adaptation, the first issue coming out just a month before the show’s premiere, and it seemed that the Lucifer comic was perhaps in danger of being influenced by the Lucifer show, which, much to the dismay of the comic’s fans, was fashioned as a police procedural. Fortunately, Black’s storytelling swiftly laid those fears to rest, as she did a splendid job bringing back Lucifer’s iconic characters and making them her own.

My interest in Holly Black’s Lucifer was genuinely sparked when I reached the final page of its first issue, as Black gives us our first glimpse of Mazikeen, seated on Hell’s throne—crucified in place, in fact. Black’s portrayal of Mazikeen’s evolution as a character has been terrific. Over the course of Mike Carey’s Lucifer comics, Mazikeen evolved from the Devil’s cowled assistant, whose hidden half-face made her dialogue difficult to discern, into Lucifer’s warrior-woman and true love—a character of such significance to Lucifer that she ultimately inherited the Morningstar’s mantle, anointed the new Lightbringer by her Lord before his departure from Creation.4 With Black’s Mazikeen—now Mazikeen Morningstar—we see how much further she has evolved as Hell’s monarch. Mazikeen is now a woman of even fewer words, but her words are firmly authoritarian, and her actions are ruthlessly regal. We learn that Mazikeen agreed to be nailed to Hell’s throne as a sign of good faith to her Lilim brethren, lest she, with her newfound Lightbringer powers, rule over them as an angel rather than as a peer.5 Whereas Lucifer abandoned Hell’s throne and shrugged off his responsibilities as ruler, Mazikeen is monomaniacal in her commitment to reigning in Hell and her responsibilities to her people.

My interest in Holly Black’s Lucifer was genuinely sparked when I reached the final page of its first issue, as Black gives us our first glimpse of Mazikeen, seated on Hell’s throne—crucified in place, in fact. Black’s portrayal of Mazikeen’s evolution as a character has been terrific. Over the course of Mike Carey’s Lucifer comics, Mazikeen evolved from the Devil’s cowled assistant, whose hidden half-face made her dialogue difficult to discern, into Lucifer’s warrior-woman and true love—a character of such significance to Lucifer that she ultimately inherited the Morningstar’s mantle, anointed the new Lightbringer by her Lord before his departure from Creation.4 With Black’s Mazikeen—now Mazikeen Morningstar—we see how much further she has evolved as Hell’s monarch. Mazikeen is now a woman of even fewer words, but her words are firmly authoritarian, and her actions are ruthlessly regal. We learn that Mazikeen agreed to be nailed to Hell’s throne as a sign of good faith to her Lilim brethren, lest she, with her newfound Lightbringer powers, rule over them as an angel rather than as a peer.5 Whereas Lucifer abandoned Hell’s throne and shrugged off his responsibilities as ruler, Mazikeen is monomaniacal in her commitment to reigning in Hell and her responsibilities to her people.

I was quite invested in the emotional evolution between Mazikeen and Lucifer. When Lucifer first comes face-to-face with her in the throne room of Hell, Mazikeen is cold and distant in the face of her erstwhile lover and Lord, but she still clearly harbors intense admiration for Lucifer as the legendary arch-rebel. When Lucifer is commanded to bend the knee upon arrival, Mazikeen interjects, “No. He may remain standing. I would be disappointed if he bent his head to anyone.” Lucifer’s admiration for Mazikeen is equal, and it was interesting to see him express uncharacteristic vulnerability before his one true love:

LUCIFER. Who dares hold you here?

MAZIKEEN. I am the ruler of Hell. I am the Lightbringer. Do not presume on our old friendship.…You kept my mark. I am touched.

LUCIFER. You said I would be a coward if I did not.

MAZIKEEN. I didn’t think you cared what I had to say.…

LUCIFER. I could free you. Command me, Mazikeen. Command me and I will not fail you.

MAZIKEEN. You have already failed me, my Lord. Go. That’s the only command I have to give you.6

As the story progresses, Black gives us the sense that Lucifer is rather lovesick for Mazikeen, and that Mazikeen, beneath her hardened outer shell, is deeply hurt by Lucifer having left her. Hell hath no fury like Hell’s matriarch scorned, and Mazikeen eventually loses her icy cool and attacks her long-lost lover. “You left me with a power I barely understood,” she shouts at Lucifer. “You left me in the world you remade. You left me!” “I’m here now,”7 Lucifer reassures Mazikeen, and indeed it is only his heartfelt kiss which rescues her from Yahweh’s mind control (more on that below). Their fiery passion for one another slowly but surely rekindles over the issues, and it was interesting to see them regain something resembling their old dynamic.

Black explained early on that her Lucifer was pitched between the poles of Neil Gaiman’s mischievous trickster and Mike Carey’s coldhearted bastard, and this slightly more human Lucifer was worked out not only in his dynamic with Mazikeen but his dynamic with his brother, the Heaven-ousted, alcoholic angel Gabriel. Following in the tradition of Carey’s Lucifer, which had a great deal of levity to it, Black’s Lucifer has many moments of comic relief, the majority of which come courtesy of Gabriel as he and his unlikely partner Lucifer embark on a strange buddy-cop journey through various realms to find God’s killer. Lucifer and Gabriel of course have history, as in Carey’s comic Lucifer’s chief tension in Heaven was with the authority of Gabriel rather than that of Michael,8 and it was likewise Gabriel instead of Michael who bested Lucifer in battle during the War in Heaven.9 The dynamic between Lucifer and Gabriel in Black’s comic has a very human feel to it—the feel of siblings who have quarreled in the past and, however much they might have moved on as significant time has lapsed, continue to irk each other. While their mutual disdain for one another is mostly expressed in a lighthearted way—“Every angel’s hallelujah must have been particularly fervent the day you got kicked out of Heaven,”10 Lucifer at one point remarks to his irritating brother—Gabriel seems to really resent his superior sibling. As the first arc of Black’s Lucifer run concludes and it is revealed to both the reader and Gabriel himself that it was he who delivered the deathblow to Yahweh and injured Lucifer, Gabriel expresses profound ambivalence. On the one hand, he is clearly frustrated with Lucifer as the rebellious yet still favored son of God, groaning, “you got to be the bad son, so the rest of us were stuck with being good forever,” but on the other hand Gabriel finds some perverse satisfaction in out-sinning the original sinner: “But I guess it turns out that I’m much worse than you ever were. That must piss you off. At least I’ve got that.”11 It will be interesting to see where Lucifer will take the deicide Gabriel, who has decided to take Mazikeen up on her offer, entering into her service in exchange for help discovering who it was who stole his memories. “If I can’t be blessed, then let me be a curse,” Gabriel states. “A curse on Heaven.”12

Black explained early on that her Lucifer was pitched between the poles of Neil Gaiman’s mischievous trickster and Mike Carey’s coldhearted bastard, and this slightly more human Lucifer was worked out not only in his dynamic with Mazikeen but his dynamic with his brother, the Heaven-ousted, alcoholic angel Gabriel. Following in the tradition of Carey’s Lucifer, which had a great deal of levity to it, Black’s Lucifer has many moments of comic relief, the majority of which come courtesy of Gabriel as he and his unlikely partner Lucifer embark on a strange buddy-cop journey through various realms to find God’s killer. Lucifer and Gabriel of course have history, as in Carey’s comic Lucifer’s chief tension in Heaven was with the authority of Gabriel rather than that of Michael,8 and it was likewise Gabriel instead of Michael who bested Lucifer in battle during the War in Heaven.9 The dynamic between Lucifer and Gabriel in Black’s comic has a very human feel to it—the feel of siblings who have quarreled in the past and, however much they might have moved on as significant time has lapsed, continue to irk each other. While their mutual disdain for one another is mostly expressed in a lighthearted way—“Every angel’s hallelujah must have been particularly fervent the day you got kicked out of Heaven,”10 Lucifer at one point remarks to his irritating brother—Gabriel seems to really resent his superior sibling. As the first arc of Black’s Lucifer run concludes and it is revealed to both the reader and Gabriel himself that it was he who delivered the deathblow to Yahweh and injured Lucifer, Gabriel expresses profound ambivalence. On the one hand, he is clearly frustrated with Lucifer as the rebellious yet still favored son of God, groaning, “you got to be the bad son, so the rest of us were stuck with being good forever,” but on the other hand Gabriel finds some perverse satisfaction in out-sinning the original sinner: “But I guess it turns out that I’m much worse than you ever were. That must piss you off. At least I’ve got that.”11 It will be interesting to see where Lucifer will take the deicide Gabriel, who has decided to take Mazikeen up on her offer, entering into her service in exchange for help discovering who it was who stole his memories. “If I can’t be blessed, then let me be a curse,” Gabriel states. “A curse on Heaven.”12

“I left home to find my fortune. To no longer be constrained by our Father’s narrow worldview. By our Father’s gifts. By our Father’s anything.”13

Much like Mike Carey’s Lucifer, Holly Black’s Lucifer is at its best when it’s exploring the deep complexities of Lucifer’s struggle for freedom from God—his Father, Yahweh. In Carey’s Lucifer, the autonomy-obsessed angel dedicated every fiber of his being to escaping the will of God. In Black’s Lucifer, the once more newly fallen angel is finally freed from God’s will by virtue of the Almighty’s demise, but the angelic son’s response to his divine Father’s death infuses the character with fresh ambiguity. Falsely accused of dealing Yahweh a fatal blow by his brother Gabriel—sent by the heavenly host to rain justice down on the Devil in exchange for his return to the Silver City—Lucifer expresses his willingness to investigate the cosmic whodunit. When Gabriel questions why, Lucifer’s response is rather ambiguous: “Because no one gets to kill God but me. And because He was my Father, too.”14

Once the mystery of the death of God is finally solved, Lucifer finds himself somewhat lost. Previously, Lucifer tried his damnedest to escape God, and more recently he was preoccupied with solving God’s murder, but with both God and His murder mystery gone, Lucifer is left with nothing to do. He sits alone in Ex Lux, almost trying to convince himself that he is pleased: “Here’s to you, Dad. One last drink to speed you on your way. Good-bye and good riddance.” The narrator, however, reveals—much like Milton’s Epic Voice in Paradise Lost—that within, Lucifer suffers far more than he’s willing to show: “Once, Lucifer defined himself in opposition to his heavenly Father. Now there is no one to oppose. No one to escape. No one to hate. He keeps turning that absence over in his mind, deliberately provoking himself, as a human might poke a tongue into the socket of a lost tooth. Perhaps even the Devil can mourn.”15 Interestingly, Lucifer lets on that he is perhaps aware of being more similar to his Father than he’d like to think when he reveals a dark secret: he was in fact the reason for Yahweh’s departure from Creation. While his heavenly rebellion was foreseen and even nudged along by Yahweh, Lucifer’s abandonment of his duties in Hell was not part of the Divine Plan, and was in turn wholly unacceptable to God, hence His abandonment of Creation. “My true rebellion was not leading an army against Heaven,” Lucifer explains to his brother Raphael. “It was handing over the key to Hell to Morpheus.…He [Yahweh] abandoned the world. And then I suppose I abandoned it, too. Like father, like son.”16

Once the mystery of the death of God is finally solved, Lucifer finds himself somewhat lost. Previously, Lucifer tried his damnedest to escape God, and more recently he was preoccupied with solving God’s murder, but with both God and His murder mystery gone, Lucifer is left with nothing to do. He sits alone in Ex Lux, almost trying to convince himself that he is pleased: “Here’s to you, Dad. One last drink to speed you on your way. Good-bye and good riddance.” The narrator, however, reveals—much like Milton’s Epic Voice in Paradise Lost—that within, Lucifer suffers far more than he’s willing to show: “Once, Lucifer defined himself in opposition to his heavenly Father. Now there is no one to oppose. No one to escape. No one to hate. He keeps turning that absence over in his mind, deliberately provoking himself, as a human might poke a tongue into the socket of a lost tooth. Perhaps even the Devil can mourn.”15 Interestingly, Lucifer lets on that he is perhaps aware of being more similar to his Father than he’d like to think when he reveals a dark secret: he was in fact the reason for Yahweh’s departure from Creation. While his heavenly rebellion was foreseen and even nudged along by Yahweh, Lucifer’s abandonment of his duties in Hell was not part of the Divine Plan, and was in turn wholly unacceptable to God, hence His abandonment of Creation. “My true rebellion was not leading an army against Heaven,” Lucifer explains to his brother Raphael. “It was handing over the key to Hell to Morpheus.…He [Yahweh] abandoned the world. And then I suppose I abandoned it, too. Like father, like son.”16

Perhaps the most significant development in the relationship between Lucifer and God is Yahweh’s resurrection/metamorphosis. God is dead at the start of Black’s Lucifer, but in fact Yahweh’s corpse becomes cocooned,17 emerging late in Black’s run as a dark, malevolent monster of a God—a caricature of the demonic deity imagined by the Romantic Satanists. This demonic Yahweh plans to reshape Creation and strip its creatures of free will: “I am a new God. A God of fire and brimstone. I scorn free will. And I mean to remake the world in my image.”18 Yet this God is not all-powerful, as Yahweh abdicated the Throne of God, which was assumed by the young Elaine Belloc at the close of Carey’s series. Elaine has struggled to remain a neutral deity, but her restoration of Lucifer’s Morningstar powers,19 while unrequested by the fallen angel, enables Lucifer to confront the reborn God in the Silver City. “No one can ever say you weren’t ambitious,” the demonic Yahweh scoffs at Lucifer. “Hubris, they call it. I will not miss you. You were a good idea, messily rendered. A first draft. I will make you again and make you better. Just as I have remade myself. I will remake everything.” As Yahweh insists on his absolute power over Creation—“This world is mine. You are mine. I made it and I made you”—Lucifer counters with his characteristic pride: “Not everything you make belongs to you.…Whatever you are, you may have some of Him in you. Perhaps you stole His power as you stole mine. But you are not my Father.”20 That last line is very telling, for while Lucifer mocks the demon God because He lacks the omnipotence of Yahweh, Lucifer also seems to say that he has even greater contempt for this monster on God’s Throne because it is not his true Father, Yahweh.

Perhaps the most significant development in the relationship between Lucifer and God is Yahweh’s resurrection/metamorphosis. God is dead at the start of Black’s Lucifer, but in fact Yahweh’s corpse becomes cocooned,17 emerging late in Black’s run as a dark, malevolent monster of a God—a caricature of the demonic deity imagined by the Romantic Satanists. This demonic Yahweh plans to reshape Creation and strip its creatures of free will: “I am a new God. A God of fire and brimstone. I scorn free will. And I mean to remake the world in my image.”18 Yet this God is not all-powerful, as Yahweh abdicated the Throne of God, which was assumed by the young Elaine Belloc at the close of Carey’s series. Elaine has struggled to remain a neutral deity, but her restoration of Lucifer’s Morningstar powers,19 while unrequested by the fallen angel, enables Lucifer to confront the reborn God in the Silver City. “No one can ever say you weren’t ambitious,” the demonic Yahweh scoffs at Lucifer. “Hubris, they call it. I will not miss you. You were a good idea, messily rendered. A first draft. I will make you again and make you better. Just as I have remade myself. I will remake everything.” As Yahweh insists on his absolute power over Creation—“This world is mine. You are mine. I made it and I made you”—Lucifer counters with his characteristic pride: “Not everything you make belongs to you.…Whatever you are, you may have some of Him in you. Perhaps you stole His power as you stole mine. But you are not my Father.”20 That last line is very telling, for while Lucifer mocks the demon God because He lacks the omnipotence of Yahweh, Lucifer also seems to say that he has even greater contempt for this monster on God’s Throne because it is not his true Father, Yahweh.

“This is the third time you’ve tried to destroy the world. Someone should really congratulate me on how right I was about you.”21

Despite Black’s interesting depiction of the power struggle between the paternal God and His insubordinate angelic son, perhaps the most interesting commentary on Lucifer’s issues with parental authority comes with the revelation that he is no longer simply a son but a father himself. It is revealed that the carnal relations Lucifer indulged in with the Japanese underworld goddess Izanami-no-Mikoto at the very end of Carey’s series22 produced a Satanic son, Takehiko, who has grown up with a deep-seated hatred for his father. Izanami spells out the similarities between the Yahweh–Lucifer and Lucifer–Takehiko dynamics:

IZANAMI. Did I not tell you that all things come full circle, Prince of Hell? A disapproving father, a rebellious son. All so familiar, is it not?.…Just as you were the cause of your Father’s undoing, Lucifer, so shall your son be the cause of yours.

LUCIFER. You think an ominous tone and a hint of prophecy will get under my skin? I don’t think you remember my Father well at all.23

Lucifer is indeed his Father’s son, as he displays when brought face-to-face with his own offspring. Izanami has urged Takehiko to usurp the throne of Hell from Mazikeen, who is forced to face the upstart prince in battle—and thereby break her oath to the Lilim to be bound to her infernal seat. “You’re just a little mote of my energy,” Lucifer sneers at the son who challenges him. “A spark I could reach out and extinguish.” “I am not just some piece of you. I am nothing like you!” desperately cries Takehiko.24 It was a moment much reminiscent of Carey’s flashback to the War in Heaven, when a defeated but defiant Lucifer scorns his Father Yahweh’s explanation that His angelic sons are “the aspects of myself through which I act”: “No! I am myself. Not a limb or an organ of yours. I separate myself from you. You can kill me. But you cannot claim me back!”25 Interestingly, while Yahweh’s response was to relocate Lucifer to Hell, where he could rule (even if he was fulfilling another aspect of the Divine Plan), Lucifer is simply dismissive of his domineering son: “Now go away, little spark, before I get angry.”26

The struggle between Lucifer and Takehiko not only calls to mind Carey’s depiction of the tension between Lucifer and Yahweh but also Milton’s depiction of the tension between Satan and his son Death in Paradise Lost. When Milton’s Satan reaches the gates of Hell en route to Eden (II.643ff.), the crowned specter of Death boasts that he is Hell’s true ruler and aggressively asserts himself as Satan’s “King and Lord” (II.699), which throws the fallen angel into a fiery rage: “…Incens’t with indignation Satan stood / Unterrifi’d, and like a Comet burn’d…” (II.707–08). This of course is a mirror image of Satan’s conflict with his own Father, Almighty God, as “maistring Heav’n’s Supreme” (IX.125) was Satan’s overreaching ambition, after all. Takehiko is not monstrous like Milton’s Death—notwithstanding his temporary transformation into a towering blob of viscera, induced by the first sight of his father—but his tension with Lucifer is extremely reminiscent of Milton’s scene. Of course, unlike Milton’s Satan, Black’s Lucifer does not appear at all interested in forming an alliance with his son (unlike the demonic Yahweh, who recruits Takehiko for the purposes of the new Divine Plan27). In their encounter, Lucifer easily subdues Takehiko, skewering him to a slab of rock. “You can’t just mean to leave him like that. He’s your son,” Gabriel remarks to his brutal brother as they are about to depart from Hell. “A sword through the stomach is nothing compared to what our Father did to us,” Lucifer coldly replies. “If he wants to be in this family, he better toughen up.”28 The Devil’s son motif could have easily slipped into disastrous camp, but Black executed the concept splendidly, establishing an interesting conflict between Lucifer and Takehiko, which is something I’m certainly looking forward to seeing unfold as the series progresses.

“You could have had Heaven, you know. You had Hell. Humans have called you the prince of this world for as long as anyone can remember.…You want what you can’t have. Too bad you’ve already had everything. Poor spoiled Lucifer. Daddy’s favorite. No hill left to climb?”29

Holly Black has done a phenomenal job of reestablishing Lucifer’s classic characters, particularly the Morningstar himself. Indeed, Black has succeeded in maintaining Vertigo’s Lucifer as the place to find the true heir of the sympathetic and sublime Satan created by Milton and embraced by the Romantics. In fact, my favorite moment of Black’s Lucifer run was when, in the realm of The Dreaming, Lucifer confronts a dream of the Devil—“Luciferian energy” manifested in the form of a gigantic, red, horned, goateed demon.30 I found it quite perfectly symbolic of how Vertigo’s Lucifer achieves what even Satanism proper falls short of: presenting to the world a modern-day manifestation of the Devil descended from the Miltonic-Romantic tradition, vanquishing popular stereotypes associated with Satan in the process.

Holly Black has done a phenomenal job of reestablishing Lucifer’s classic characters, particularly the Morningstar himself. Indeed, Black has succeeded in maintaining Vertigo’s Lucifer as the place to find the true heir of the sympathetic and sublime Satan created by Milton and embraced by the Romantics. In fact, my favorite moment of Black’s Lucifer run was when, in the realm of The Dreaming, Lucifer confronts a dream of the Devil—“Luciferian energy” manifested in the form of a gigantic, red, horned, goateed demon.30 I found it quite perfectly symbolic of how Vertigo’s Lucifer achieves what even Satanism proper falls short of: presenting to the world a modern-day manifestation of the Devil descended from the Miltonic-Romantic tradition, vanquishing popular stereotypes associated with Satan in the process.

The one thing that bothered me about Black’s Lucifer run was the product of it only being a yearlong run, which proved somewhat problematic in terms of pacing the story out. Several times I found myself wanting to spend more time exploring the story Black was telling, and feeling somewhat unsatisfied on account of the writer’s eagerness to move on. There was a tendency for the characters to hurry or be hurried from place to place, and Lucifer’s rushed confrontation with the demonic Yahweh—and Michael Demiurgos,31 whose recreation is monumentally significant but with which little has been done thus far—was the perfect example. Black, who is a successful writer of fiction, was open about struggling to squeeze Lucifer into her daunting schedule. While reluctant to accept Vertigo’s offer of a monthly comic series, Black felt compelled to take the opportunity to write for Lucifer because she’d get to delve into the fascinating character created by the brilliant minds of Neil Gaiman and Mike Carey. Black certainly succeeded in continuing their visions in her own unique way—the ideal outcome in such an endeavor—but it is truly a shame that she could not continue working on the comic indefinitely. I am as sorry to see Holly Black leave Lucifer as I was uneasy to hear that she’d be restarting what Mike Carey finished a decade prior.

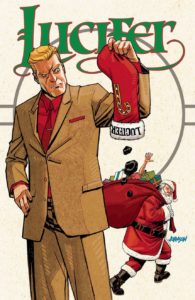

It was announced at the 2016 New York Comic Con that Richard Kadrey would be handed the reins of Lucifer after Black’s yearlong run on the comic. Black and Kadrey collaborated on a lighthearted Christmas issue of Lucifer for the holiday season, but the merits of Kadrey’s contributions to Lucifer remain to be seen. “I’ve been living with the devil for a long time,” Kadrey reassures us. “It was a distant relationship for most of my life, but has become a closer, more intimate one over these last few years.…Let’s face it: if you’re going to be interested in angels, you’re going to gravitate to the most fascinating one. That’s Lucifer. Hands down. End of discussion.” I’m hoping for the best, and certainly Black has already done the difficult work for Kadrey in terms of bringing back Lucifer’s iconic characters, reestablishing their relationships, and setting them on intriguing new journeys. If handled properly by Kadrey, there is much to look forward to: Lucifer’s rekindled relationship with Mazikeen and their newfound endeavor “to kill God”32; the demonic Yahweh’s effort to enthrall Creation; Takehiko’s quest for revenge against his diabolical father; Mazikeen’s fight for the coveted throne of Hell; the political intrigue of Beelzebub, Asmodeus, and Izanami, now in the Japanese goddess’ realm; Elaine’s struggle to remain a neutral deity; and Gabriel’s search for a new purpose in life. Most importantly, there is ever more opportunity to explore the labyrinthine Lucifer, whose incessant search for self-authorship continues to fascinate and astonish.

It was announced at the 2016 New York Comic Con that Richard Kadrey would be handed the reins of Lucifer after Black’s yearlong run on the comic. Black and Kadrey collaborated on a lighthearted Christmas issue of Lucifer for the holiday season, but the merits of Kadrey’s contributions to Lucifer remain to be seen. “I’ve been living with the devil for a long time,” Kadrey reassures us. “It was a distant relationship for most of my life, but has become a closer, more intimate one over these last few years.…Let’s face it: if you’re going to be interested in angels, you’re going to gravitate to the most fascinating one. That’s Lucifer. Hands down. End of discussion.” I’m hoping for the best, and certainly Black has already done the difficult work for Kadrey in terms of bringing back Lucifer’s iconic characters, reestablishing their relationships, and setting them on intriguing new journeys. If handled properly by Kadrey, there is much to look forward to: Lucifer’s rekindled relationship with Mazikeen and their newfound endeavor “to kill God”32; the demonic Yahweh’s effort to enthrall Creation; Takehiko’s quest for revenge against his diabolical father; Mazikeen’s fight for the coveted throne of Hell; the political intrigue of Beelzebub, Asmodeus, and Izanami, now in the Japanese goddess’ realm; Elaine’s struggle to remain a neutral deity; and Gabriel’s search for a new purpose in life. Most importantly, there is ever more opportunity to explore the labyrinthine Lucifer, whose incessant search for self-authorship continues to fascinate and astonish.

Holly Black has undeniably impressed the hell out of me with her treatment of the Lucifer she inherited from Mike Carey—especially with her yearlong Lucifer run’s preservation of the Morningstar’s Miltonic-Romantic spirit—and so I wish to close here by giving Black the last word:

After a year of writing Lucifer, I have thought a lot about the perennial fascination of the Devil. His story is a dynastic story: it’s about kings and princes and wars and thrones, and at the same time it’s a family story about brothers and fathers and sons.…And I think we love him, if we love him, because he’s a bad son; because he’s ambitious; because he’s a screw-up; because he’s a rebel; [because] he spits in the face of the establishment, the government, the rules. And he was the brightest angel, before he fell, but maybe he was pushed … a little bit. So, it’s been an honor to spend a year with the Devil…

Notes

1. Holly Black, Lucifer #5: Cold Heaven: Part Five: Son of Mystery.↩

2. See Mike Carey, Lucifer: Evensong (New York: DC Comics, 2007), pp. 72–74.↩

3. See Mike Carey, Lucifer: Morningstar (New York: DC Comics, 2006), p. 139ff.↩

4. See ibid., pp. 68–72.↩

5. See Holly Black, Lucifer #8: Father Lucifer: Part Two: The Not-So-Fortunate Fall.↩

6. Holly Black, Lucifer #2: Cold Heaven: Part Two: Lady Lucifer.↩

7. Holly Black, Lucifer #10: Father Lucifer: Part Four: World Unchained.↩

8. See Mike Carey, Lucifer: The Wolf Beneath the Tree (New York: DC Comics, 2005), pp. 12–13, 32–33, 37–42.↩

9. See Carey, Lucifer: Evensong, pp. 132–36.↩

10. Black, Lucifer #2.↩

11. Black, Lucifer #5.↩

12. Ibid.↩

13. Holly Black, Lucifer #4: Cold Heaven: Part Four: Hosts.↩

14. Holly Black, Lucifer #1: Cold Heaven: Part One: Prodigal Sons.↩

15. Holly Black, Lucifer #7: Father Lucifer: Part One: Practicing to Deceive.↩

16. Black, Lucifer #8.↩

17. See Black, Lucifer #7.↩

18. Holly Black, Lucifer #9: Father Lucifer: Part Three: Prodigal Sons.↩

19. See Holly Black, Lucifer #11: Omniscient Narration.↩

20. Holly Black, Lucifer #12: Endgame: Father Lucifer: Part Six.↩

21. Ibid.↩

22. See Carey, Lucifer: Evensong, pp. 56–62.↩

23. Black, Lucifer #9.↩

24. Black, Lucifer #10.↩

25. Carey, Lucifer: Evensong, p. 135.↩

26. Black, Lucifer #10.↩

27. See Black, Lucifer #11.↩

28. Black, Lucifer #10.↩

29. Holly Black, Lucifer #3: Cold Heaven: Part Three: Mothers of All.↩

30. See Black, Lucifer #4.↩

31. See Black, Lucifer #10.↩

32. Black, Lucifer #12.↩