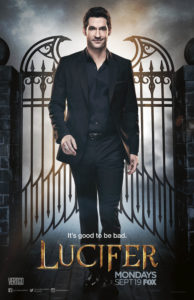

I decided to cease writing episodic reviews of Lucifer on Fox on account of the show having been entirely uprooted from Mike Carey’s rich comic. The premiere episode of Lucifer’s second season highlighted that the show has become irredeemably campy, with its supernatural characters simply all-too-human and Lucifer himself reduced to little more than a running joke in his own show. The Satanic Scholar’s blog reviews for the thirteen-episode first season of Lucifer on Fox have been relocated here:

S1:E1, “Pilot” (1/27/2016)

S1:E2, “Lucifer, Stay. Good Devil” (2/2/2016)

S1:E3, “The Would-Be Prince of Darkness” (2/9/2016)

S1:E4, “Manly Whatnots” (2/16/2016)

S1:E5, “Sweet Kicks” (2/23/2016)

S1:E6, “Favorite Son” (3/16/2016)

S1:E7, “Wingman” (3/18/2016)

S1:E8, “Et Tu, Doctor?” (3/20/2016)

S1:E9, “A Priest Walks into a Bar” (3/22/2016)

S1:E10, “Pops” (3/29/2016)

S1:E11, “St. Lucifer” (4/12/2016)

S1:E12, “#TeamLucifer” (4/21/2016)

S1:E13, “Take Me Back To Hell” (5/16/2016)

I was someone who read Vertigo’s Lucifer comic religiously, finding in Mike Carey’s Lucifer Morningstar character the Miltonic-Romantic Satan’s true heir. With this in mind, I feel I was quite supportive of the effort to bring Lucifer to the small screen, and exceedingly understanding of the inevitable alterations to the source material necessitated by the endeavor of translating a sympathetic Satan to the mainstream medium of television. I understood, for instance, that while Vertigo’s Lucifer comic could revel in its irreverence, Fox’s Lucifer show would understandably have to soften its sacrilegious aspects so as to avoid early cancelation (the very title of the show alone was destined to court controversy), and that while Vertigo’s Lucifer comic could go wild with supernatural spectacle (a cigar chomping ex-cherub, a living tarot deck, angelic wars, alternate universes, a young girl assuming the Throne of God, etc.), Fox’s Lucifer show would understandably be forced to downplay the heavenly and hellish elements by virtue of its limited budget. Many fans of the Lucifer comic were irate by the time the show’s initial trailer was released, but I understood the multifaceted challenges involved in carrying out Lucifer on Fox successfully, and I was willing to play Devil’s advocate, hoping for the best. All that I expected of Fox’s Lucifer was for it to stay true to the spirit of the comic’s characters, particularly the titular angelic anti-hero, and after spending time watching and writing about the entire first season of the show, I simply could not say that the creators of Lucifer on Fox either accomplished or even made an honest effort to accomplish this.

I was someone who read Vertigo’s Lucifer comic religiously, finding in Mike Carey’s Lucifer Morningstar character the Miltonic-Romantic Satan’s true heir. With this in mind, I feel I was quite supportive of the effort to bring Lucifer to the small screen, and exceedingly understanding of the inevitable alterations to the source material necessitated by the endeavor of translating a sympathetic Satan to the mainstream medium of television. I understood, for instance, that while Vertigo’s Lucifer comic could revel in its irreverence, Fox’s Lucifer show would understandably have to soften its sacrilegious aspects so as to avoid early cancelation (the very title of the show alone was destined to court controversy), and that while Vertigo’s Lucifer comic could go wild with supernatural spectacle (a cigar chomping ex-cherub, a living tarot deck, angelic wars, alternate universes, a young girl assuming the Throne of God, etc.), Fox’s Lucifer show would understandably be forced to downplay the heavenly and hellish elements by virtue of its limited budget. Many fans of the Lucifer comic were irate by the time the show’s initial trailer was released, but I understood the multifaceted challenges involved in carrying out Lucifer on Fox successfully, and I was willing to play Devil’s advocate, hoping for the best. All that I expected of Fox’s Lucifer was for it to stay true to the spirit of the comic’s characters, particularly the titular angelic anti-hero, and after spending time watching and writing about the entire first season of the show, I simply could not say that the creators of Lucifer on Fox either accomplished or even made an honest effort to accomplish this.

I understand that the Lucifer show had to be more down-to-earth than the Lucifer comic, but Fox brought the empyrean rebel Lucifer far too down-to-earth, and it served to make the Morningstar more an irritating playboy than an admirable anti-hero. In the Lucifer comic, for instance, the princely fallen angel possessed élite elegance and the aristocratic arrogance to match, and while the Lucifer show tried to make the Devil debonair and smooth-tongued, Lucifer’s sophistication suffered greatly throughout the first season, the titanic rebel against Almighty God displaying a penchant for pop culture and petty gossip. What’s more, while the Lucifer comic always emphasized that Lucifer is a son of God, Carey’s Lucifer was never childish, and he always possessed lofty existential aspirations—namely absolute autonomy, the pursuit of which was his raison d’être. Fox’s Lucifer, on the other hand, presented us with an extremely adolescent version of the fallen angel—a mildly mischievous and oversexed man who with each week drifted further away from his comic incarnation until the last traces of Carey’s Lucifer were lost.

I understand that the Lucifer show had to be more down-to-earth than the Lucifer comic, but Fox brought the empyrean rebel Lucifer far too down-to-earth, and it served to make the Morningstar more an irritating playboy than an admirable anti-hero. In the Lucifer comic, for instance, the princely fallen angel possessed élite elegance and the aristocratic arrogance to match, and while the Lucifer show tried to make the Devil debonair and smooth-tongued, Lucifer’s sophistication suffered greatly throughout the first season, the titanic rebel against Almighty God displaying a penchant for pop culture and petty gossip. What’s more, while the Lucifer comic always emphasized that Lucifer is a son of God, Carey’s Lucifer was never childish, and he always possessed lofty existential aspirations—namely absolute autonomy, the pursuit of which was his raison d’être. Fox’s Lucifer, on the other hand, presented us with an extremely adolescent version of the fallen angel—a mildly mischievous and oversexed man who with each week drifted further away from his comic incarnation until the last traces of Carey’s Lucifer were lost.

Season one of Lucifer on Fox got off to a tepid start and peaked at its sixth episode, “Favorite Son,” yet even there the contrast between the show and the comic was drastic, for while the writers had starring lead Tom Ellis practically recite lines from the source material,1 the actor’s delivery made his Lucifer come off more as a hurt and awkward child than as the epic personality that bursts off the pages of the Lucifer comics. The final blow to the Vertigo Lucifer character was delivered in the season finale, when a mortally wounded Lucifer begs for his heavenly Father’s help as he vows to amend his ways: “I’ll be the son you always wanted me to be. I’ll do as you ask, go where you want me to.” That is not Vertigo’s Lucifer, and the Devil’s quasi deathbed repentance served to tear the heart from the Lucifer Morningstar character the show is based upon—the uncompromisingly independent figure who, when he at long last comes face-to-face with his Father Yahweh at the conclusion of his 75-issue series, proudly reasserts his independence: “I’ve always been the one who said no to you, Father.”2 Fox clearly failed to do the Devil of Vertigo’s Lucifer justice, instead delivering an ersatz Satan. Perhaps the silver lining of Lucifer on Fox was that it seemed to serve as the impetus for resurrecting Vertigo’s Lucifer comic, teen fantasy novelist Holly Black picking up where Mike Carey left off—and doing a much better job than the creators of the Lucifer TV show.

I believe Lucifer on Fox could have been a decent translation of the Vertigo comic, even if the creators of the show had to resort to the familiar police procedural model to appeal to a broader audience. Yet perhaps the failed endeavor of properly transforming Vertigo’s Lucifer into a TV show demonstrates the danger of the Prince of Darkness being invoked in popular culture: while a popular medium like television serves as an efficient means of exposing mass audiences to modern-day manifestations of the Miltonic-Romantic Lucifer, the populism of the medium threatens to dilute any such distinguished Devils in the process. On a more positive note, while Fox’s Lucifer show may have been loosely based on Vertigo’s Lucifer comic, to say the least, it illustrated that it is possible to have Satan as the star of a commercially successful, mainstream TV show—his proud name gracing the small screen—which is a glaring example of the fallen angel’s current cultural ascension. All the same, I definitely would have preferred that the show fail for being too faithful to the comic rather than be successful for straying too far from it.

Notes

1. See Neil Gaiman, The Sandman: Season of Mists (New York: DC Comics, 2010), “Episode 2”; Mike Carey, Lucifer: Evensong (New York: DC Comics, 2007), p. 143.↩

2. Carey, Lucifer: Evensong, p. 160.↩