Romantic renditions of the Satan of Milton’s Paradise Lost in the visual arts are the most idealized images of the fallen archangel, and the leap forward from artistic attempts at envisioning Milton’s Satan—to say nothing of Satan in general—prior to Romanticism is unmistakable. Having said that, there were a number of noteworthy proto-Romantic renderings of the Miltonic Satan. Indeed, the evolution of Milton’s Satan in the visual arts runs parallel to the character’s evolution in literary criticism. It was only during Romanticism that the Miltonic Lucifer was lauded as a sublime revolutionary hero, but the debate over Satan’s claim to hero status originated in the seventeenth century, when Milton’s Satan, his villainy notwithstanding, was deemed Paradise Lost’s “hero” in a technical sense—the active character who moves the story along and is triumphant (over Adam); in the eighteenth century, Milton’s hero-villain was absorbed into debates over the sublime, the abundant majesty and grandeur of Satan’s heroism largely eclipsing his flaws; by the turn of the nineteenth century, Milton’s Satan became the full-fledged hero of Paradise Lost, nobly defying a tyrannical God. The character’s visual representations over the centuries reflect this very same trajectory.

While one can identify proto-Romantic Satanic grandeur even in the very first illustrations of Milton’s Satan, produced by Henry Aldrich (1647–1710), Bernard Lens (1631–1708), and John Baptist de Medina (1659–1710) for the 1688 Jacob Tonson edition of Paradise Lost, ultimately these first attempts at bringing Milton’s apostate angel to life show signs not so much of the sublime Romantic Satanism later to come as the residual diabolism of traditional Christian iconography. While the 1688 Paradise Lost’s depictions of Satan for Book I and Book II might concede some of the classical air Milton awarded the rebel angel, the grotesque vestiges of the bestial and buffoonish image imposed upon the Devil by medievalism are overpowering, and indeed by the illustration for Book IX Satan is reduced to stereotypical, cloven-hoofed caricature. These first attempts therefore fail to adequately capture the spirit of Milton’s Satan, the ruined yet toweringly majestic archangel who retains much of his native celestial radiance, his mighty fallen form likened to the Sun obscured by a misty horizon or eclipsed by the Moon (I.592–99). Shortcomings similar to those of the original 1688 artwork dogged Milton illustration up until the eighteenth-century artwork which is included here, which does begin to approach proper Miltonic magnificence. The works of the artists below portray Paradise Lost’s Prince of Darkness as not only powerful but increasingly human and angelically attractive in appearance, thereby anticipating Romanticism’s heightened vision of the Satanic.

While one can identify proto-Romantic Satanic grandeur even in the very first illustrations of Milton’s Satan, produced by Henry Aldrich (1647–1710), Bernard Lens (1631–1708), and John Baptist de Medina (1659–1710) for the 1688 Jacob Tonson edition of Paradise Lost, ultimately these first attempts at bringing Milton’s apostate angel to life show signs not so much of the sublime Romantic Satanism later to come as the residual diabolism of traditional Christian iconography. While the 1688 Paradise Lost’s depictions of Satan for Book I and Book II might concede some of the classical air Milton awarded the rebel angel, the grotesque vestiges of the bestial and buffoonish image imposed upon the Devil by medievalism are overpowering, and indeed by the illustration for Book IX Satan is reduced to stereotypical, cloven-hoofed caricature. These first attempts therefore fail to adequately capture the spirit of Milton’s Satan, the ruined yet toweringly majestic archangel who retains much of his native celestial radiance, his mighty fallen form likened to the Sun obscured by a misty horizon or eclipsed by the Moon (I.592–99). Shortcomings similar to those of the original 1688 artwork dogged Milton illustration up until the eighteenth-century artwork which is included here, which does begin to approach proper Miltonic magnificence. The works of the artists below portray Paradise Lost’s Prince of Darkness as not only powerful but increasingly human and angelically attractive in appearance, thereby anticipating Romanticism’s heightened vision of the Satanic.

William Hogarth (1697 – 1764)

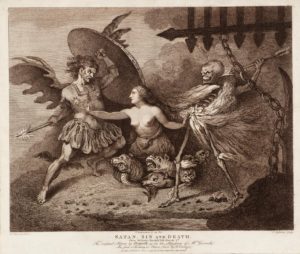

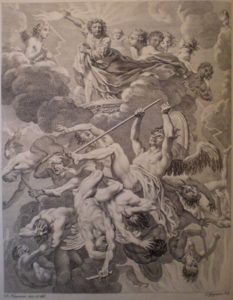

Hogarth was a multifaceted English artist: a painter, engraver, and satirist, to name only a few of his many skills. Hogarth’s unfinished oil painting Satan, Sin and Death (A Scene from Milton’s “Paradise Lost”) (1735–40) is the real shifting point in Satanic iconography. This may not be apparent at first glance, considering Satan’s overwhelming monstrousness: sallow skin, taloned feet, a shaggy face, burning red eyes, blue lips, and fanged teeth. Nevertheless, Hogarth’s Satan, with his Roman tunic, shield and spear, bears a martial appearance, and while the original Paradise Lost illustrations of 1688 also had Satan don these classical accoutrements, Hogarth’s Satan appears not comical but powerful, striding violently forward to face off with Death himself. While Hogarth’s Satan, Sin and Death captures Sin perfectly (upwardly beautiful woman, downwardly malformed monster), Death is a complete copout (a charred skeleton, as opposed to Milton’s shadowy figure), and Satan is far too bestial to fit Milton’s description of the Devil, still a towering archangel who retains vestiges of his heavenly origins, rather like an obscured Sun. All the same, Hogarth’s Satan is not a comical figure like the caricatured fallen angel of the 1688 designs; he exudes explosive energy and his figure is imposing, and in this he anticipates the depictions of Milton’s Satan wrought by the Romantic artists of the 1790s, such as Fuseli, Barry, Westall, and Lawrence. While Satan is still no handsome Devil in the 1792 engraving of Hogarth’s Satan, Sin and Death executed by Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827) and John Ogbourne (1725–1795), he is notably less demonically bestial, which shows that a proto-Romantic Satan can be wrested from Hogarth’s original.

Hogarth was a multifaceted English artist: a painter, engraver, and satirist, to name only a few of his many skills. Hogarth’s unfinished oil painting Satan, Sin and Death (A Scene from Milton’s “Paradise Lost”) (1735–40) is the real shifting point in Satanic iconography. This may not be apparent at first glance, considering Satan’s overwhelming monstrousness: sallow skin, taloned feet, a shaggy face, burning red eyes, blue lips, and fanged teeth. Nevertheless, Hogarth’s Satan, with his Roman tunic, shield and spear, bears a martial appearance, and while the original Paradise Lost illustrations of 1688 also had Satan don these classical accoutrements, Hogarth’s Satan appears not comical but powerful, striding violently forward to face off with Death himself. While Hogarth’s Satan, Sin and Death captures Sin perfectly (upwardly beautiful woman, downwardly malformed monster), Death is a complete copout (a charred skeleton, as opposed to Milton’s shadowy figure), and Satan is far too bestial to fit Milton’s description of the Devil, still a towering archangel who retains vestiges of his heavenly origins, rather like an obscured Sun. All the same, Hogarth’s Satan is not a comical figure like the caricatured fallen angel of the 1688 designs; he exudes explosive energy and his figure is imposing, and in this he anticipates the depictions of Milton’s Satan wrought by the Romantic artists of the 1790s, such as Fuseli, Barry, Westall, and Lawrence. While Satan is still no handsome Devil in the 1792 engraving of Hogarth’s Satan, Sin and Death executed by Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827) and John Ogbourne (1725–1795), he is notably less demonically bestial, which shows that a proto-Romantic Satan can be wrested from Hogarth’s original.

Francis Hayman (1708 – 1776)

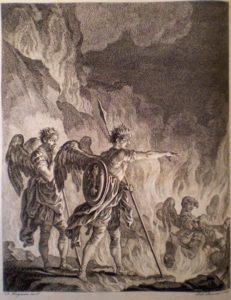

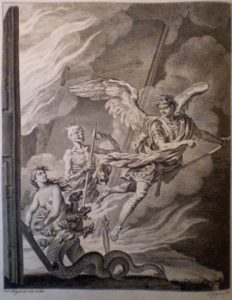

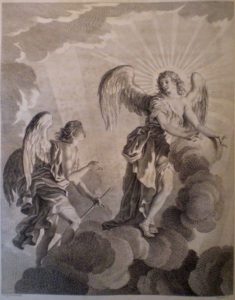

Hayman was a painter and book illustrator, as well as a founding member of the Royal Academy of Arts, established in 1768. For his deep commitment to the promotion of English art, not least as the former President of the Society of Artists (1761–1791)—a forerunner to the Royal Academy—Hayman was appointed the first Librarian of the RA in 1770. The Satan of Hayman’s illustrations for the two-volume edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost published by J. & R. Tonson and S. Draper in 1749 prefigure the Romantic Satan in various respects: this quasi-classically garbed, angelic-winged Satan’s form and face are wholly human, and the only trace of the demonic is to be found in his wildly disheveled hair and his distorted facial features, suggesting nefariousness. Hayman anticipates the artwork of Stothard, Corbould, Dayes, Harvey, and even Doré later in the nineteenth century by imagining Milton’s Satan as a martially outfitted human figure. It has been observed that Hayman’s human Satan—perhaps all-too-human, given the fallen angel’s knee-breeches—is somewhat puppet-like, and as such is certainly not the titanic figure imagined by Romantic artists like Fuseli, Barry, Westall, Lawrence, or even Blake. Yet by portraying the Devil as not horrifying but human, and by restoring the fallen angel’s feathery angelic wings, Hayman’s illustrations of Milton’s Satan were precursors to Romantic Satanic art.

Hayman was a painter and book illustrator, as well as a founding member of the Royal Academy of Arts, established in 1768. For his deep commitment to the promotion of English art, not least as the former President of the Society of Artists (1761–1791)—a forerunner to the Royal Academy—Hayman was appointed the first Librarian of the RA in 1770. The Satan of Hayman’s illustrations for the two-volume edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost published by J. & R. Tonson and S. Draper in 1749 prefigure the Romantic Satan in various respects: this quasi-classically garbed, angelic-winged Satan’s form and face are wholly human, and the only trace of the demonic is to be found in his wildly disheveled hair and his distorted facial features, suggesting nefariousness. Hayman anticipates the artwork of Stothard, Corbould, Dayes, Harvey, and even Doré later in the nineteenth century by imagining Milton’s Satan as a martially outfitted human figure. It has been observed that Hayman’s human Satan—perhaps all-too-human, given the fallen angel’s knee-breeches—is somewhat puppet-like, and as such is certainly not the titanic figure imagined by Romantic artists like Fuseli, Barry, Westall, Lawrence, or even Blake. Yet by portraying the Devil as not horrifying but human, and by restoring the fallen angel’s feathery angelic wings, Hayman’s illustrations of Milton’s Satan were precursors to Romantic Satanic art.

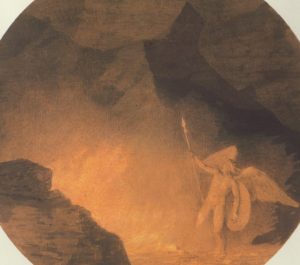

John Robert Cozens (1752 – 1797)

Cozens was a painter of watercolor landscapes, having studied under his father, the Russian-born British landscape painter Alexander Cozens (1717–1786). In 1776, Cozens executed Satan Summoning His Legions, a roundel depicting the Hell-doomed Satan of Paradise Lost standing alone on what Milton calls “the Beach / Of that inflamed Sea” (I.299–300), with shield and spear in hand calling back to his unseen forces still billowing in the torturous hellfire. This image foreshadows Romantic Satanic sublimity in various respects: Satan is here a rather diminutive figure, dwarfed by the massive, sublime underworld that surrounds him—which itself anticipates John Martin’s Miltonic mezzotints of the mid-1820s—but as an angelic-winged nude with youthfully handsome facial features and dramatically windswept hair, this Satan was a sign of things to come in Romanticism’s treatment of the Satanic.

“Anti-Satanist” Milton critics have argued relentlessly that the Romantic Satan is not Milton’s Satan, insisting that the Romantics distorted the Devil of Paradise Lost. Christian apologist C. S. Lewis, for instance, asserted that Milton’s Satan only ever became “an object of admiration and sympathy” because “rebellion and pride came, in the romantic age, to be admired for their own sake” (A Preface to Paradise Lost, pp. 94, 133). Yet to argue that there is nothing unorthodox or even peculiar about Milton’s Satan is disingenuous—especially for C. S. Lewis, given his resort to rather unMiltonic portrayals of the Satanic in his own literary works. Milton’s Satan was problematic to pious readers from the moment of Paradise Lost’s publication in 1667, and with the advent of Romanticism the Miltonic Satan had merely come into his own. It was a “long metamorphosis,” in the words of Peter L. Thorslev, Jr., and when Satan “re-emerged in the romantic mind, he was no longer the (larval) serpent of the later books of Paradise Lost [IX.157–91, 412 ff.; X.504–77], but had reassumed his archangelic wings and had become intimately associated with romantic rebellion in the name of the new humanist self-assertion—particularly in association with his brother rebel against God, Prometheus” (“The Romantic Mind Is Its Own Place,” pp. 251–52). Thorslev’s is a beautiful image and a perfect metaphor, for Romanticism’s Promethean reevaluation of Milton’s Satan is extremely evident in the visual arts of the era, and that the germ of this heroicized Satan is to be found in Paradise Lost itself is reflected in the above proto-Romantic renderings of Milton’s Satan.