“O foul descent! that I who erst contended

With Gods to sit the highest, am now constrain’d

Into a Beast, and mixt with bestial slime,

This essence to incarnate and imbrute,

That to the highth of Deity aspir’d…”

— Paradise Lost (1667), IX.163–67

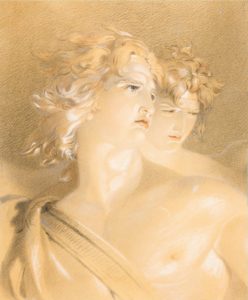

So laments Milton’s Satan as he contemplates possessing the slimy serpent in order to carry out the temptation in Eden. Lord Byron—“master-Satanist”1 of Romanticism’s “Satanic School”—relieved Lucifer of this “foul descent” in Cain (1821), as both Byron himself and the Byronic fallen angel deny the popular identification of the Eden serpent with Lucifer. Indeed, Byron’s proud “Master of spirits” (I.i.99) scoffs at the notion that a superior spiritual being free to roam the cosmos—“One who aspired to be what made thee” (I.i.126), as he puts it to Adam’s firstborn son—would covet what little the material world has to offer, let alone in the shape of a creeping creature (I.i.216–45). And as in Milton’s Paradise Lost, wherein Satan’s “form had yet not lost / All her Original brightness, nor appear’d / Less than Arch-Angel ruin’d” (I.591–93), Byron’s Cain presents the fallen Lucifer as a sublime sight:

…A shape like to the angels,

Yet of a sterner and a sadder aspect

Of spiritual essence.…

Yet he seems mightier far than them, nor less

Beauteous, and yet not all as beautiful

As he hath been, and might be: sorrow seems

Half of his immortality. (I.i.80–96)

A Brief History of Satan’s Sullied Beauty

Romanticism’s handsome Devil was wholly indebted to the Miltonic Satan, for Paradise Lost’s portrait of the fallen angel was a remarkably radical break from Christian tradition. Traditionally, Satan’s celestial magnificence was transformed into monstrousness as he was cast into Hell, his prelapsarian splendor sometimes even stripped at the moment of his exile from Heaven. Sullying Satan’s former beauty and majesty was a dramatic way of expressing the cataclysmic nature of his fall, as attested to by the Old Testament passages which the Church Fathers, when formulating the Devil’s official biography, took as veiled descriptions of the renegade angel’s heavenly war against God and subsequent infernal imprisonment (Isaiah 14:12–15; Ezekiel 28:12–19). In Paradise Lost, Milton pays homage both to the prideful Lucifer of Isaiah, who sought to scale the heavens and equal the Almighty Himself, and to the beautifully bejeweled “anointed cherub” of Ezekiel, whose radiance led to rejection of God, when describing the angelic aristocrat’s sparkling celestial abode (V.756–66). Yet the splendiferous structure that Milton’s industrious fallen angels erect in Hell—“Pandæmonium, the high Capitol / Of Satan and his Peers” (I.756–57)—is not necessarily less magnificent, for this “City and proud seat / Of Lucifer” (X.424–25) is described by Milton as a marvelous sight far outshining all sublime structures throughout human history (I.710–30), within which Satan is seated atop an incomparably splendid throne (II.1–10).

These glittering palaces reflect the Miltonic Lucifer’s luster: Satan the heavenly rebel angel is described as “Sun-bright” (VI.100), and yet Satan the hellish fallen angel is still likened to the Sun, though as obscured by a misty horizon or eclipsed by the Moon (I.592–99). In short, Milton’s Satan remains in possession of a considerable degree of his “Original brightness” (I.592), as does the fallen “Satanic Host” (VI.392), which Milton likens to a lightning-scorched but nonetheless stately forest (I.612–15). The fallen rebel angels, despite their diminished glory, bear “Godlike shapes and forms / Excelling human, Princely Dignities” (I.358–59), and no one is as princely and godlike as Satan himself, who even in the midst of damnation cuts a truly dazzling figure:

…he above the rest

In shape and gesture proudly eminent

Stood like a Tow’r; his form had yet not lost

All her Original brightness, nor appear’d

Less than Arch-Angel ruin’d, and th’ excess

Of Glory obscur’d.…

…Dark’n’d so, yet shone

Above them all th’ Arch-Angel… (I.589–600)

Milton calls his Satan “the Prince of Darkness” (X.383), but as the prestigious Miltonist John Leonard aptly notes, though “a ‘disstarred’ Lucifer,” Milton’s Satan “is not the prince of darkness, but the prince of twilight, a denizen of Heaven, splendid even in exile.”4 Consider what a far cry this is from the arch-fiend of medieval Christianity, which was wholeheartedly dedicated to humbling the prideful angel. During the Middle Ages, Satan was portrayed sometimes as a frightful fiend, sometimes as a fumbling fool,5 but always as a malformed monster, and the greatest of these deformed Devils was Dante’s Lucifer.

Modern Satanism’s Goatish Devil

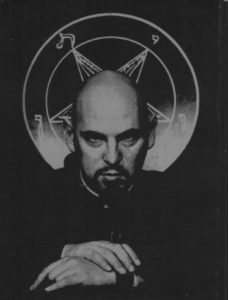

When Church of Satan founder Anton Szandor LaVey staked his flag on Satanism in 1966 with his codification of the world’s first openly Satanic creed and accompanying aboveground Satanic organization, he laid claim to an authoritative position on not only Satanic philosophy but on Satanic aesthetics as well. As it happens, LaVey’s proved to be an aesthetic far removed from the infernal elegance descended from the Miltonic-Romantic tradition, reflected most perfectly in that cultural tradition’s Satan, a true Prince of Darkness.

Fleshly fun was indeed the focus of the much publicized ceremonies hosted throughout the late 1960s at “the Black House”—LaVey’s San Francisco home, and the newborn Church of Satan’s headquarters—which featured melodramatic rites in darkened, red-lit rooms over the sound of mournful organ music, “the Black Pope” LaVey himself presiding over salaciously sacrilegious rituals in campy attire, not least a horned skull cap. Poking fun at the Christian Church by satirizing traditional Satanic imagery was not unheard of; consider the eighteenth-century Hell-Fire Clubs,10 whose mischievous members channeled the spirit of the infernal as they mocked sacred rites, or even the young Lord Byron dressing as a monk and drinking from a skull cup during orgiastic revels held at his gothic manor, Newstead Abbey.11 However, while LaVey and his sable-robed associates were undeniably having fun at Christianity’s expense, the Black Pope seems to have taken the satirical Satan look he donned rather seriously.

Satanism’s advantage over mainstream religion is certainly its strong sense of humor,12 but it is difficult to deny that Satanists tend to drift into self-parody when insisting with the utmost conviction that their philosophy is fit only for a natural-born “alien elite”—Satanists as a superior subspecies of Nietzschean supermen13—while appearing in fancy dress, rebranded with colorful names drawn from various demons or cinematic villains (something even Peter H. Gilmore, LaVey’s successor as the Church of Satan’s High Priest, has criticized as crass and silly14) or, worse yet, absurd adopted surnames like “Ruthless” or “Murder.” (One such former prominent member of the Church of Satan would even resort to subdermal implants to give the impression that he had horns.) LaVey himself, though the consummate showman, appears to have been at least somewhat cognizant of the clash between Satanism’s dark doctrines—Social Darwinian might-makes-right and Machiavellian manipulation for personal gain—with its carnivalesque aesthetic. For example, the year 1967 saw LaVey preside over the world’s first Satanic wedding, baptism, and funeral, and while the Black Pope wore the horned cap for the first two affairs, when it came to the more somber third—performed for a deceased serviceman, no less—LaVey showed some restraint and hung up the horns. The Church of Satan High Priest would later abandon his horned cap image altogether in the 1970s, when he decided that it was time to “stop performing Satanism and start practicing it.”15 But LaVeyan Satanism would be stuck with that imagery, famously crystallized in the 1970 documentary film Satanis: The Devil’s Mass, which has provided stock footage for just about every documentary on Satanism since.

Satanism’s advantage over mainstream religion is certainly its strong sense of humor,12 but it is difficult to deny that Satanists tend to drift into self-parody when insisting with the utmost conviction that their philosophy is fit only for a natural-born “alien elite”—Satanists as a superior subspecies of Nietzschean supermen13—while appearing in fancy dress, rebranded with colorful names drawn from various demons or cinematic villains (something even Peter H. Gilmore, LaVey’s successor as the Church of Satan’s High Priest, has criticized as crass and silly14) or, worse yet, absurd adopted surnames like “Ruthless” or “Murder.” (One such former prominent member of the Church of Satan would even resort to subdermal implants to give the impression that he had horns.) LaVey himself, though the consummate showman, appears to have been at least somewhat cognizant of the clash between Satanism’s dark doctrines—Social Darwinian might-makes-right and Machiavellian manipulation for personal gain—with its carnivalesque aesthetic. For example, the year 1967 saw LaVey preside over the world’s first Satanic wedding, baptism, and funeral, and while the Black Pope wore the horned cap for the first two affairs, when it came to the more somber third—performed for a deceased serviceman, no less—LaVey showed some restraint and hung up the horns. The Church of Satan High Priest would later abandon his horned cap image altogether in the 1970s, when he decided that it was time to “stop performing Satanism and start practicing it.”15 But LaVeyan Satanism would be stuck with that imagery, famously crystallized in the 1970 documentary film Satanis: The Devil’s Mass, which has provided stock footage for just about every documentary on Satanism since.

Romantic artwork may have oscillated between the sublime and the ridiculous, but the iconography of modern Satanism has leaned much more toward the latter, despite LaVeyan Satanists’ patrician pretensions. For instance, the Church of Satan leadership has been at pains to distance Satanism from the “shock-value Satanism” associated with metal music (classical music is true Satanic music, they maintain16), but is the Satan of LaVeyan Satanism really all that different from the alternately horrific and humorous Devils which adorn heavy metal album artwork? The Church of Satan’s is “the figure championed by the likes of Mark Twain, Milton, and Byron as the independent critic who heroically stands on his own,”17 insists Gilmore, but one would be hard-pressed to identify any such Satan within the imagery produced by LaVeyan Satanism over its half-century span. Their Satan is not the godlike arch-rebel out of Milton and the Romantics; theirs is the goatish arch-fiend out of medieval Christianity, and Satanism’s goatish aesthetic is encapsulated in the Church of Satan’s official emblem: the Sigil of Baphomet.

While Éliphas Lévi was undeniably influenced by the Romantic Satanists who came before him,22 and while the idea of a union of opposites is certainly a familiar Romantic trope—absolutely central to Byronism, for instance—Baphomet quite simply cannot be considered an accurate representation of the Romantic Satan (nor did Lévi intend it to be23). Lévi’s Baphomet and its myriad recreations situate Satan much more in the tradition of medieval Christianity, which emphasized a beastly Devil—an image Milton and later the Romantics broke away from in imagining Satan as a handsome and heroic figure, restoring considerable luster to Lucifer’s much tarnished image. Somehow, the Miltonic-Romantic tradition’s radiant and regal Satan appears to have no place within LaVeyan Satanism—nor, as we will see, within its various offshoots.

Notes

1. Clara Tuite, Lord Byron and Scandalous Celebrity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 233.↩

2. William Hazlitt, Lectures on the English Poets (1818), “Lecture III: On Shakespeare and Milton,” in The Romantics on Milton: Formal Essays and Critical Asides, ed. Joseph Anthony Wittreich, Jr. (Cleveland: The Press of Case Western Reserve University, 1970), p. 385.↩

3. “Prince of Pride” (princeps superbie) was an obscure medieval epithet for the Devil. See Jeffrey Burton Russell, Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, [1984] 1986), pp. 88, 128n. 76.↩

4. John Leonard, The Value of Milton (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016), p. 75.↩

5. See Russell, Lucifer, p. 243.↩

6. For exceptions, see Roland Mushat Frye, “Milton’s Paradise Lost and the Visual Arts,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 120, No. 4, Symposium on John Milton (Aug. 13, 1976), pp. 233–44.↩

7. Stella Purce Revard posits that Milton’s epic hero Satan is an installment in a long line of Renaissance Lucifers in her study of The War in Heaven: Paradise Lost and the Tradition of Satan’s Rebellion (Ithaca, NY and London: Cornell University Press, 1980), p. 198: “Satan, proud but magnificent, unyieldingly resolute in battle, emerges in the Renaissance poems wearing the full splendor of epic trappings. To these poems we owe in large measure the hero Satan as he is developed in Paradise Lost. Renaissance poets drew on two traditions to depict Satan or Lucifer: the hexaemeral and the epic. Hexaemera described Lucifer as a prince, glorious and unsurpassed, whose ambition caused him to strive above his sphere; epics described their heroes as superhuman in battle and accorded them, whatever their arrogance or mistakes in judgment, ‘grace’ to offend, even as they are called to account for their offenses. The Lucifer of the Renaissance thus combines Isaiah’s Lucifer with Homer’s Agamemnon, Virgil’s Turnus, and Tasso’s Rinaldo. Milton’s Satan, in turn, follows the Renaissance Lucifer and is both the prince depicted in hexaemera and the classical battle hero.”↩

8. See Watson Kirkconnell, The Celestial Cycle: The Theme of Paradise Lost in World Literature with Translations of the Major Analogues (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1952), pp. 59–61 (Torquato Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberate, 1581); 221 (Giambattista Marini’s La Strage degli Innocenti, 1610); 236 (Giambattista Andreini’s L’Adamo, 1613); 350–51 (Joseph Beaumont’s Psyche, or Love’s Majesty, 1648); 414–15 (Joost van den Vondel’s Lucifer, 1654).↩

9. Percy Bysshe Shelley, Essay on the Devil and Devils, in Shelley’s Prose: or the Trumpet of a Prophecy, ed. David Lee Clark, pref. Harold Bloom (New York: New Amsterdam Books, 1988), p. 268.↩

10. See Chris Mathews, Modern Satanism: Anatomy of a Radical Subculture (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2009), pp. 16–17; Ruben van Luijk, Children of Lucifer: The Origins of Modern Religious Satanism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 66–67.↩

11. See Phyllis Grosskurth, Byron: The Flawed Angel (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1997), pp. 76–77; Benita Eisler, Byron: Child of Passion, Fool of Fame (New York: Vintage Books, 2000), pp. 173–75; Fiona MacCarthy, Byron: Life and Legend (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2002), pp. 79, 87.↩

12. Anton LaVey was emphatic about the centrality of humor to Satanism. In his essay on “How to be God (or the Devil),” featured in The Devil’s Notebook (Los Angeles: Feral House, 1992)—a book “Dedicated to the men, whoever they are, who invented the Whoopee Cushion, the Joy Buzzer, and the Sneeze-O-Bubble” (p. 3)—the fifth of LaVey’s nine guidelines reads, “A sense of humor is a must; a god who can’t laugh at himself or find comic relief is a dull Jehovah and most definitely un-Satanic” (p. 66). “Those who are humorless should not be taken seriously,” reasoned LaVey in his posthumous publication Satan Speaks! (Los Angeles: Feral House, 1998), as “They take themselves so seriously, they leave no room for others to do likewise” (p. 165). While undeniably a misanthrope, LaVey insisted he was no mope, just “a very happy man in a compulsively unhappy world” (Satan Speaks!, p. 170).↩

13. LaVey voiced his sense of Satanic superiority rather loudly in The Satanic Bible (New York: Avon Books, [1969] 2005) when he characterized “the Satanist” as “THE HIGHEST EMBODIMENT OF HUMAN LIFE!” (p. 45). LaVey would later explain, “Satanism is the first time in history where a master race can be built on genetically predisposed, like-minded people — not based on the genes that make them white, black, blue, brown or purple — but the genes that make them Satanists.” Quoted in Blanche Barton, The Secret Life of a Satanist: The Authorized Biography of Anton LaVey (Los Angeles: Feral House, [1990] 1992), p. 212.↩

14. See Peter H. Gilmore, “The Myth of the ‘Satanic Community’ and Other Virtual Delusions,” in The Satanic Scriptures (Baltimore, MD: Scapegoat Publishing, 2007), p. 174.↩

15. LaVey, quoted in Barton, p. 125.↩

16. See, for example, Peter H. Gilmore, “Diabolus In Musica,” in The Satanic Scriptures, pp. 112–35.↩

17. Peter H. Gilmore, “What, the Devil?” in ibid., p. 209.↩

18. See LaVey, The Satanic Bible, pp. 53, 104.↩

19. See, for example, Jeffrey Burton Russell, Witchcraft in the Middle Ages (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, [1972] 1984), pp. 194–98; Peter H. Gilmore, “Baphomet,” in Satanism Today: An Encyclopedia of Religion, Folklore, and Popular Culture, ed. James R. Lewis (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2001), pp. 20–21; Mathews, pp. 12–13; van Luijk, pp. 136–37.↩

20. For more on Éliphas Lévi (a.k.a. Alphonse-Louis Constant), see Mathews, pp. 104–5; van Luijk, pp. 127–44.↩

21. LaVey, The Satanic Bible, p. 136: “The symbol of Baphomet was used by the Knights Templar to represent Satan.…In its ‘pure’ form the pentagram is shown encompassing the figure of a man in the five points of the star—three points up, two pointing down—symbolizing man’s spiritual nature. In Satanism the pentagram is also used, but since Satanism represents the carnal instincts of man, or the opposite of the spiritual nature, the pentagram is inverted to perfectly accommodate the head of the goat—its horns, representing duality, thrust upwards in defiance; the other three points inverted, or the trinity denied.”↩

22. See van Luijk, pp. 132–36.↩

23. See ibid., pp. 136–39.↩