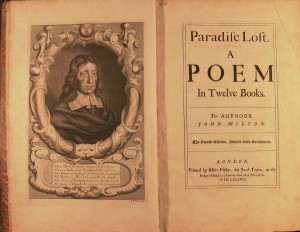

As demonstrated in part one, Michael Aquino was a Satanist much more in touch with Satanism’s Miltonic-Romantic roots than Anton LaVey, founder of the Church of Satan, history’s first ever aboveground Satanic organization. The learned Aquino was in an ideal position—particularly when he set out to form his own irreligious institution upon having apostatized from LaVey’s Church of Satan, which Aquino felt had become, in more ways than one, commercialized—to steer Satanism into more Miltonic-Romantic territory. Curiously, Aquino, the Satanist who found in Milton’s Paradise Lost “one of the most exalted statements of Satanism ever written”1 and who asserted that the “Miltonian Lucifer is, in fact, our Satanic man,”2 swiftly snuffed out any hope of this happening. Aquino’s alternative to LaVey’s Church of Satan was to be the Temple of Set, which overlooked Milton and the Romantic Satanists inspired by the revolutionary genius, Aquino staking his flag in ancient Egypt and adopting the evil Egyptian deity of Set as his organization’s central icon.

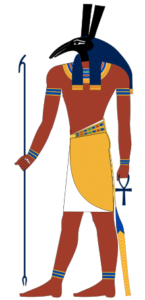

Aquino, not content with merely dismissing LaVey as a crass charlatan and a bloodless opportunist, opted for a mystical narrative in his portrayal of his fallout with the Black Pope.3 Aquino had always believed in a personal Satan, and he insisted that LaVey shared this belief during the Church of Satan’s formative years. With LaVey’s loss of faith in the fallen angel, Aquino claimed, the Church of Satan had degenerated into the “Church of Anton,” and so the Prince of Darkness had stripped LaVey of his “Infernal Mantle.”4 Having departed from the Church of Satan in the summer of 1975, Aquino invoked Satan for guidance, and was apparently instructed by the infernal entity as follows: “Reconsecrate my Temple and my Order in the true name of Set. No longer will I accept the bastard title of a Hebrew fiend.”5 The Hebraic Satan, it turns out, was in actuality a corruption of the older Egyptian desert deity Set. In addition to providing marching orders, Satan/Set dictated to Aquino The Book of Coming Forth by Night (1975), the work to serve as the foundational text for Setianism, which would liberate Satanism from the confines of its Judeo-Christian context—and LaVey’s betrayal. Ironically enough, as Aquino was insisting that Setianism was Satanism having shed its Judeo-Christian skin, his characterization of LaVey was colored by his reading of Milton, as scholars Asbjørn Dyrendal, James R. Lewis, and Jesper Aa. Petersen observe in their study of The Invention of Satanism: “Ever the well-read and poetically inclined academic, Michael Aquino…obliquely has LaVey follow the trajectory of Milton’s Satan, from proud archangel to deluded, hissing snake, ever more caught up by his own ‘sins.’ ”6

LaVey’s version of the proceedings, beginning with his own letter to the Church of Satan members who Aquino reached out to as part of his dramatic departure,7 was far less fanciful. LaVey maintained that the Satanism of the Church of Satan was purely atheistic from the start, all of the rituals and titles—indeed, the very “Church of Satan” moniker—embraced merely for their symbolic significance. To be fair, while LaVey undeniably believed in the power of ritual magic—not merely as cathartic theatrics but the ability to induce change in the physical world through ceremonial spells8—LaVey’s early writings and media appearances do appear to reflect a belief in a Satan that was only ever a team mascot, essentially. Interestingly enough, while Aquino appeared to be more Miltonic-minded than LaVey, the fundamental atheism of LaVeyan Satanism sets it more in the tradition of Romantic Satanism, as the nineteenth-century Romantics did not believe a literal Devil—who had been brought to his deathbed by the eighteenth-century Enlightenment—and embraced the Satan of Milton’s epic for his manifest poetic power. In any event, while Aquino’s open belief in a personal Satan was incongruent with the bedrock atheism of LaVeyan Satanism, LaVey was willing to tolerate the supernatural preferences of Aquino and various other early Church of Satan members so as not to thin his ranks as he was trying to get his organization off the ground. As the Church of Satan successfully established itself, however, LaVey felt less and less the need to hold on to such “occultniks,” and after the schism LaVey would go on to claim that Aquino and his cohorts were deliberately driven out of the Church of Satan so that Satanism could evolve.

While LaVey’s reality-based take on Aquino’s break with the Church of Satan is certainly more plausible than Aquino’s version of infernal intervention, the extent to which the once loyal lieutenant’s Satanic exodus impacted LaVey is disputable. While Aquino insisted that the Church of Satan effectively died in 1975, LaVey was dismissive of the Setians, scoffing at the idea that the desertion of these “Egyptoids”9 was of much significance. Superficially at least, LaVey paid Aquino and company little mind, which was quite the opposite of Aquino, who hovered over LaVey for the remainder of his life, even creepily including LaVey’s divorce proceedings as an appendix to his two-volume text, The Church of Satan.10 On the other hand, LaVey clearly became much more cynical, misanthropic, and detached following the events of the summer of ’75. LaVey had already ceased group ritual activities at the Black House in 1972, when the Black Pope decided that it was time to “stop performing Satanism and start practicing it,”11 but after 1975 he dissolved the Church of Satan’s local chapters (“grottoes”) which dotted the U.S. and beyond, and withdrew into the Black House to remain an effective recluse. Whether LaVey did so because he truly desired to evolve Satanism beyond the blasphemous fun-and-games of its first decade or because the Church of Satan turned out to be a disappointing endeavor—or some mixture of the two—remains open to debate.

Ironically, as LaVey sat out the proceedings of the Satanic Panic that gripped the dark decade of the 1980s, the modern-day witch hunt saw Aquino, who stepped into the media spotlight formerly enjoyed by the Black Pope, accused of child abuse as part of an alleged Satanic scandal at the daycare center of the Presidio military base in San Francisco.12 Aquino’s prestigious martial and academic accomplishments surely made him a target for the religious paranoiacs and media opportunists who imagined a vast Satanist network within the government engaging in Satanic ritual abuse, and while Aquino’s name was ultimately cleared as the baseless accusations were demystified, his background—not least his field specialty of “psychological warfare” in the Army—ensured that he would continue to be speculated upon by conspiracy theorists to this day.

Ironically, as LaVey sat out the proceedings of the Satanic Panic that gripped the dark decade of the 1980s, the modern-day witch hunt saw Aquino, who stepped into the media spotlight formerly enjoyed by the Black Pope, accused of child abuse as part of an alleged Satanic scandal at the daycare center of the Presidio military base in San Francisco.12 Aquino’s prestigious martial and academic accomplishments surely made him a target for the religious paranoiacs and media opportunists who imagined a vast Satanist network within the government engaging in Satanic ritual abuse, and while Aquino’s name was ultimately cleared as the baseless accusations were demystified, his background—not least his field specialty of “psychological warfare” in the Army—ensured that he would continue to be speculated upon by conspiracy theorists to this day.

Aquino may have certainly removed Satanism—or at least his own Egyptianized version of it—from the Judeo-Christian context of LaVeyan Satanism, but by opting for an anachronistic Egyptian context, Aquino’s Temple of Set was bound to be much more obscure than LaVey’s Church of Satan.13 While Satanists may not like it, Western culture remains predominantly Judeo-Christian, yet that context is precisely why Satanism continues to survive and thrive—even twenty years after LaVey’s death in 1997—for as Satan remains the ultimate antithesis, embracing that infernal figure will continue to provoke outrage and intrigue. Having swapped Satan for Set—to say nothing of the many other esoteric exchanges—Aquino’s organization, which was presented from the start as the successor to the Church of Satan, is unlikely to outlast LaVey’s. On the other hand, perhaps this kind of obscurity was what Aquino desired for the Temple of Set all along, as he took issue with LaVey making Satanism (relatively) “popular,” i.e., accessible to the masses. Aquino yearned for Satanism to be more of an esoterically elite occult order a la nineteenth-century magical fraternities, and this he aspired to achieve by going Egyptian, transforming Satanism into Setianism.

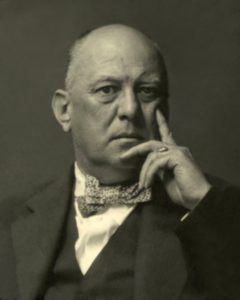

Satanism had overshot Romanticism, Aquino having overlooked the entire Miltonic-Romantic tradition. (I believe Ruben van Luijk, the author of Children of Lucifer: The Origins of Modern Religious Satanism, is far too generous when he writes that within “the Temple of Set, one could say, Byron’s Lucifer eventually found its adherents after all, albeit masked as a cult to an Egyptian deity.”14) Then again, it is perhaps more accurate to conclude that Aquino hadn’t overshot but in fact undershot Romanticism, for with the Temple of Set he was not so much guided by the ancient Egyptian deity of Set as he was the infamous early-twentieth-century English occultist Aleister Crowley.15 Crowley reacted to his bleak and oppressive Christian upbringing with diabolical defiance, fancying himself “the Great Beast 666” and taking perverse pleasure in being pilloried in the press as “the wickedest man in the world.” Crowley may have touched on Miltonic-Romantic territory with his “Hymn to Lucifer”—the poem wherein “sun-souled Lucifer” is presented as Eden’s enlightener (“The Key of Joy is disobedience”16)—but the ambitious magician aspired to move beyond simply blaspheming Christianity and enter into a more magical (or “magickal”) context. This landed Crowley—at least for a time—in Egyptian territory. The Book of the Law (1904), Crowley claimed, was dictated to the evil Englishman during his Cairo honeymoon by an entity called Aiwass—a messenger of the ancient Egyptian deity Horus—and this inspired writing was to serve as the foundational text for Crowley’s new religion of Thelema. Aquino’s deliberate emulation of these aspects of “Crowleyanity” are unmistakable, and indeed Aquino presented Thelema, Satanism, and Setianism as a continuum: the ancient Egyptian god Set, Aquino claimed, revealed himself to Crowley as his “Opposite Self” (i.e., Horus), then to LaVey as Satan—a bastardization of Set, the Setians maintain—and finally to Aquino as his true self, Set.17 Whatever is to be made of this bizarre narrative, one thing is certain: there is no room for the Miltonic-Romantic Lucifer within it.

Whether Aquino overshot or undershot Romanticism, what the history of Satanism has in the curious case of Michael Aquino and the Temple of Set is a squandered opportunity to return Satanism to its Miltonic-Romantic roots. In the end, perhaps it was for the best. I have argued that Romantic Satanism was far more impressive than organized Satanism, and not despite but because the Romantic Satanists did not construct some formal Satanic religion with stringent hierarchies and rigid rituals. Romantic Satanism emerged in a remarkably organic fashion: the Romantic Satanists did not work in tandem, and in some cases they were not even familiar with one another, but what their works collectively produced was the most significant rehabilitation of the figure of the fallen angel in the history of Christendom. In this respect, the Romantic Satanists spearheaded the most significant challenge to the status quo in Western history, and the fruits of their labor proved to be cultural treasures. The Satanic literature and artwork of the Romantic era remains of far greater value than anything organized Satanism has produced over its half-century span, with all its continued ritualistic paeans to infernal entities, whether they are believed to be merely symbolic or sentient.

Whether Aquino overshot or undershot Romanticism, what the history of Satanism has in the curious case of Michael Aquino and the Temple of Set is a squandered opportunity to return Satanism to its Miltonic-Romantic roots. In the end, perhaps it was for the best. I have argued that Romantic Satanism was far more impressive than organized Satanism, and not despite but because the Romantic Satanists did not construct some formal Satanic religion with stringent hierarchies and rigid rituals. Romantic Satanism emerged in a remarkably organic fashion: the Romantic Satanists did not work in tandem, and in some cases they were not even familiar with one another, but what their works collectively produced was the most significant rehabilitation of the figure of the fallen angel in the history of Christendom. In this respect, the Romantic Satanists spearheaded the most significant challenge to the status quo in Western history, and the fruits of their labor proved to be cultural treasures. The Satanic literature and artwork of the Romantic era remains of far greater value than anything organized Satanism has produced over its half-century span, with all its continued ritualistic paeans to infernal entities, whether they are believed to be merely symbolic or sentient.

Ironically enough, immersing oneself in the poetry and prose of Milton, Byron, Shelley, Blake and others in this tradition is “occult” insofar as the term means “hidden”; in other words, a thorough understanding of this rich Miltonic-Romantic tradition is fit for an “elite” of sorts insofar as Milton’s Paradise Lost and the Romantic writings inspired by that fascinating seventeenth-century epic poem are profoundly challenging to the modern reader and altogether escape the attention of the average person today. Embracing this kind of challenge strikes me as far more worthwhile and rewarding than reciting Enochian, invoking long dead Egyptian deities, accumulating esoteric degrees, or amassing shelf loads of mass-market occult bric-a-brac. The philosophical substance to LaVeyan Satanism was arguably always overshadowed by LaVey’s skills as a showman in the ritual chamber,18 but Aquino’s infatuation with esotericism unquestionably pushed Satanism’s occult element to its absolute—and, I would argue, embarrassing—extreme. (LaVey was not wrong to sneer at Aquino for accusing him of authoritarianism while simultaneously claiming supernatural authority from a diabolical deity.19) As ironic as it might have been for the man who in the midst of warfare was inspired by reading Milton’s Paradise Lost as a Satanic epic—like the Romantic Satanists before him—to extinguish rather than cultivate Satanism’s Miltonic-Romantic spark, the occult-obsessed Aquino ultimately helped illustrate the greater value of the literary, artistic, cultural tradition of Miltonic-Romantic Satanism.

Notes

1. Michael A. Aquino, The Church of Satan: Volume I: Text & Plates ([8th ed. 1983] San Francisco: N.p., 2013), p. 73.↩

2. Michael A. Aquino, The Church of Satan: Volume II: Appendices ([8th ed. 1983] San Francisco: N.p., 2013), p. 44.↩

3. See Gavin Baddeley, Lucifer Rising: Sin, Devil Worship & Rock ‘n’ Roll (London: Plexus Publishing Limited, [1999] 2006), pp. 102–03; Chris Mathews, Modern Satanism: Anatomy of a Radical Subculture (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2009), pp. 83–84; Ruben van Luijk, Children of Lucifer: The Origins of Modern Religious Satanism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 347–48.↩

4. See Aquino, Volume II, p. 360.↩

5. Aquino, quoted in van Luijk, pp. 351–52.↩

6. Asbjørn Dyrendal, James R. Lewis, and Jesper Aa. Petersen, The Invention of Satanism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), p. 98.↩

7. See Anton Szandor LaVey, “Hoisted by His Own Patois,” in Aquino, Volume II, pp. 374–75.↩

8. See, for example, Blanche Barton, The Secret Life of a Satanist: The Authorized Biography of Anton LaVey (Los Angeles: Feral House, [1990] 1992), Ch. 17, “Curses and Coincidences,” pp. 195–98. It’s also worth noting that the original Church of Satan evolved out of LaVey’s “Magic Circle,” the group which met at LaVey’s San Francisco home for lectures on various taboo topics.↩

9. Anton Szandor LaVey, “The Church of Satan, Cosmic Joy Buzzer,” in The Devil’s Notebook, intro. Adam Parfrey (Los Angeles: Feral House, 1992), p. 29.↩

10. See Aquino, Volume II, pp. 418–25.↩

11. LaVey, quoted in Barton, p. 125.↩

12. See van Luijk, p. 363.↩

13. There is an interesting parallel with the Paradise Lost and Gods of Egypt films. Alex Proyas entered the director’s chair for Paradise Lost in the fall of 2010, and after the plug was pulled on the project just before production was set to start in early 2012, the film Proyas moved on to was Gods of Egypt. The ill-fated Paradise Lost project and the Gods of Egypt film, which was released in early 2016, overlapped with one another, both on a narrative level—an epic battle between two supernatural beings (Michael and Lucifer vs. Horus and Set) with a patriarchal deity looking on overhead (God vs. Ra), this cosmic conflict grounded by the story of two imperiled mortal lovers (Adam and Eve vs. Bek and Zaya)—and on a technical level (an aesthetic of ancient mythology filtered through science fiction), for which numerous crew members who worked on Paradise Lost with Proyas joined the director for Gods of Egypt. There are a whole host of reasons for Gods of Egypt bombing at the box office, but we can be reasonably sure that if the Paradise Lost film were released—even if it suffered from some of the same shortcomings as Gods of Egypt—it would have been more of an event on account of its greater relevance in this cultural context.↩

14. Van Luijk, p. 353.↩

15. See Baddeley, pp. 23–32; Mathews, pp. 36–38; van Luijk, pp. 306–11.↩

16. Aleister Crowley, “Hymn to Lucifer,” in Flowers From Hell: A Satanic Reader, ed. Nikolas Schreck (Washington, D.C.: Creation Books, 2001), p. 263.↩

17. See Mathews, pp. 84–85; van Luijk, p. 352.↩

18. The Satanic Bible (New York: Avon Books, [1969] 2005) would be a case in point: LaVey’s wit is evident in the various essays contained in “The Book of Lucifer” section, but these worldly observations are completely overwhelmed by The Satanic Bible’s extended coverage of Satanic ritual, which dominates a vast majority of the brief book’s pages. The Black Pope’s Satanic Bible may be the foundational text of modern Satanism, but LaVey’s published essay collections—The Devil’s Notebook and the posthumous Satan Speaks! (Los Angeles: Feral House, 1998)—are, it must be said, more worthwhile reads.↩

19. See LaVey, “Hoisted by His Own Patois,” p. 374.↩