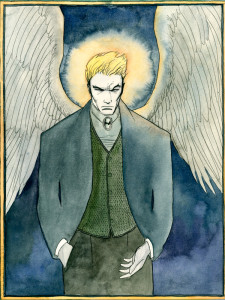

While I believe Vertigo’s Lucifer (1999 – 2006) to be the place to find the Miltonic-Romantic Satan’s successor and even superior in certain respects, Mike Carey’s anti-hero angel is, to be fair, undeniably flawed in ways distinctly different from his Miltonic and Byronic predecessors.

The pride of Carey’s Lucifer is rather narcissistic and anti-social in nature. (When his L.A. piano bar Lux is eventually burned to ash, Lucifer rebuilds it “as a cathedral without doors – a monument to his own arrogance and self-love.”1) Lucifer’s utter self-absorption precludes him from forming any significant ties to other living beings. In a 2002 interview with Comic Book Resources, Carey summed Lucifer up as “the ultimate solipsist – the guy who’d burn the world down to light his cigarette,” elaborating:

He’s not cruel, particularly – although he’s capable of cruelty – he’s just so focused on his own goals and his own needs that nobody else exists for him.…I don’t see Lucifer as evil, really: I see him as amoral…He makes his decisions purely by his own criteria, and he doesn’t care one way or the other how other people are hurt or helped by his actions.

While this sounds strikingly similar to the Romantic radical William Hazlitt’s observation that Milton’s Satan “is not the principle of malignity, or of the abstract love of evil—but of the abstract love of power, of pride, of self-will personified, to which last principle all other good and evil, and even his own, are subordinate,”2 even at his most morally culpable moments Milton’s Satan is not so icily detached as Carey’s Lucifer.

Milton’s Satan is sympathetic even as he plots his crime against humanity, shedding tears for the human couple whose ruin he must precipitate to avenge himself and his fallen brethren on God and divide the Deity’s Empire by conquering the “new World” (Paradise Lost, IV.388–92). More moving are the tears Satan sheds for the “Millions of Spirits” who fell from Heaven “For his revolt,” yet even in damnation stand faithfully before their leader (I.604–20). Milton’s Satan is certainly an imposing figure before his infernal hosts (I.331–38, II.466–75) and speaks openly about why he need not fear rebellion from them (II.21–35), but Satan’s followers do not feel oppressed but rather uplifted by their “great Commander” (I.358): recollecting “his wonted pride,” Satan “gently rais’d / Thir fainting courage, and dispell’d thir fears” (I.527, 529–30). When Milton’s soliloquizing Satan engages in a thought experiment on atonement at one point in the poem, one of the reasons he rejects the possibility of repentant submission is his “dread of shame / Among the Spirits beneath…” (IV.82–83).

A deep sense of commitment to his brothers-in-arms—his “Companions dear” (VI.419)—is one of Satan’s more endearing qualities in Paradise Lost. Despite the Miltonic magnificence of the Lucifer of Cain: A Mystery (1821), what Lord Byron’s portrait of the Prince of Pride lacks is this profound sense of loyalty to his subordinates. Byron’s Lucifer asserts himself as a “Master of spirits” (I.i.99), but his relationship with these subordinate spirits is unknowable, limited as the play is to Lucifer’s education of Cain. Carey’s Lucifer is not so ambiguous, openly expressing concern only for himself—only for his relentless quest for absolute freedom. When accused of being “an arrogant, ungrateful son of a bitch on a permanent power trip” by the character Jill Presto, Carey’s Devil pleads guilty: “Ha! Excellent. Accurate on all counts. But don’t push your luck. My good humor could evaporate at any moment.”3

When publicly declaring his rebellion in the heavenly Silver City, Carey’s Lucifer issues an open invitation, but he is quite clear that he is indifferent as to whether or not anyone marches behind him: “Angels of the host! I renounce my name and my birthright. I am Samael no longer. Now I am only what I was made to be — the Lucifer. The bearer of the light and the fire. And those of you who seek their own paths — may, if you care to, begin by following mine.”4 As Lucifer turns his back on Heaven, he inevitably attracts followers (“For a star draws many things in its wake, whether it will or no.”5), but Carey is emphatic that Lucifer “didn’t look back. He didn’t seem to care.”6 Lucifer’s superhuman struggle for self-determination is commendable, but his lack of care for his followers is rather callous, and it is undeniably a step backward from the Satan of the Miltonic-Romantic tradition.

On the other hand, like his Miltonic and Byronic forebears, the sublimity and grandeur of Carey’s Lucifer largely eclipses his behavioral imperfections, his titanic magnificence compelling readers to significantly overlook his deep flaws. There are certainly positive aspects to what Carey calls Lucifer’s “touchy pride and perverse integrity,”7 which are unique unto him. Lucifer is a Machiavellian manipulator, to be sure, but it is “a point of pride” for him to never lie outright,8 which necessitates his always keeping his word and never leaving a debt unresolved, however far he must go out of his way.9 This ambivalent virtue of brutal honesty is best outlined by the character David Easterman, who observes:

They used to call the Devil the Father of Lies. But for someone whose sin is meant to be pride, you’d think that lying would leave something of a sour taste. Too easy. Too sleazy. Too much of a coward’s tool. So my theory is that when the Devil wants to get something out of you, he doesn’t lie at all. He tells you the exact, literal truth. And he lets you find your own way to Hell.10

Pride is both the fatal flaw and the saving grace of Carey’s Lucifer, as was the case for Milton’s Satan.

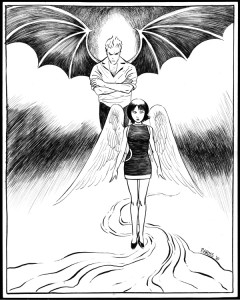

In addition to his own private morality or personal code of conduct, Carey’s Lucifer also exhibits on occasion what we might cautiously call affection. The exception to his narcissism is Mazikeen, his faithful, fiercely devoted, right-hand warrior-woman, for whom Lucifer harbors something resembling love. When in flashback we are shown Mazikeen—daughter of Lilith and future leader of the Lilim army—come before Lucifer in Hell, requesting entry into his service, the enthroned Lucifer is characteristically aloof: “Serve me if you will. I’ll never thank you for it. Your coming and your going will never impinge on my attention.”11 Nevertheless, throughout the series Lucifer is genuinely affectionate toward his friend and lover, and although he ultimately breaks Mazikeen’s hardened heart at the end of the series by resolving to exit into the void alone, Lucifer bestows upon her his “name” and “nature,” making her “the Lightbringer.”12

The self-obsessed, sociopathic Lucifer giving his very essence—his “Luciferhood”—over to his lover is a redeeming feature of the colossally arrogant angel. It is perhaps only rivaled by the respect Lucifer chooses to pay the young Elaine Belloc. When she assumes the position of God and accepts responsibility for the accompanying cosmic duties which Lucifer refused, the Morningstar tellingly states to Elaine, “For what it’s worth, I think you’ll be an improvement on the old regime.”13 His implication is that things might have turned out differently were she his God, rather than Yahweh, which is just about the best possible compliment Lucifer—the quintessential rebel—could grant a person.

In deliberately portraying Lucifer as thoroughly ambivalent, Carey took a rather Byronic approach to the arch-rebel. (It was certainly not Milton’s intention to portray his Satan as “the most heroic subject that ever was chosen for a poem…”14) In Cain, Lucifer presents himself to Adam’s firstborn son as something of a Promethean patron, claiming to “know the thoughts / Of dust, and feel for it, and with you” (I.i.100–01), as he tells Cain, but Byron’s Lucifer repeatedly belittles Cain for his mortality (I.i.123–24, 221–28, 242–46; II.i.50–60; II.ii.67–74, 95–105, 269–74, 401–24). One can certainly argue that this puts Cain in the distraught mindset that culminates in the murder of his brother Abel (II.ii.337–55, 380–88), regardless of whether or not Lucifer intended thus. Carey’s Lucifer is similarly ambivalent, compelling readers to admire his uncompromising independence, but flabbergasting them with reminders of his disdainful indifference and, on occasion, his displays of callous cruelty. Carey confesses, however, that his Lucifer ended up being far more sympathetic than even he anticipated, conceding that the “softening of the satanic hard line wasn’t something that was in the initial plan.”15 The uncanny ability of Carey’s Lucifer to confound and defy expectations is what truly secures his place in the Miltonic-Romantic-Satanic tradition.

Notes

1. Mike Carey, Lucifer: Exodus (New York: DC Comics, 2005), p. 6.↩

2. William Hazlitt, Lectures on the English Poets (1818), “Lecture III: On Shakespeare and Milton,” in The Romantics on Milton: Formal Essays and Critical Asides, ed. Joseph Anthony Wittreich, Jr. (Cleveland: The Press of Case Western Reserve University, 1970), p. 384.↩

3. Mike Carey, Lucifer: Children and Monsters (New York: DC Comics, 2001), p. 91.↩

4. Mike Carey, Lucifer: The Wolf Beneath the Tree (New York: DC Comics, 2005), p. 42.↩

5. Ibid., p. 43.↩

6. Ibid., p. 42.↩

7. Mike Carey, “Afterword: The Devil’s Business,” in Lucifer: Evensong (New York: DC Comics, 2007), p. 214.↩

8. Carey, Lucifer: Children and Monsters, p. 201.↩

9. See, for example, Carey, Lucifer: Children and Monsters, p. 140; Lucifer: A Dalliance with the Damned (New York: DC Comics, 2002), p. 66; Lucifer: The Divine Comedy (New York: DC Comics, 2003), pp. 43, 158; Lucifer: Inferno (New York: DC Comics, 2004), p. 17; Lucifer: Evensong, p. 41.↩

10. Carey, Lucifer: Children and Monsters, pp. 135–36.↩

11. Carey, Lucifer: Evensong, p. 139.↩

12. Ibid., pp. 68–72.↩

13. Mike Carey, Lucifer: Morningstar (New York: DC Comics, 2006), p. 188.↩

14. Hazlitt, p. 384.↩

15. Carey, “Afterword: The Devil’s Business,” p. 214.↩