In Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), Satan conforms conceptually to Frank S. Kastor’s analytical breakdown of Christianity’s arch-villain: “a trimorph, or three related but distinguishable personages: a highly placed Archangel, the grisly Prince of Hell, and the deceitful, serpentine Tempter.”1 Kastor’s dissection identifies three distinctive roles (the Apostate Angel, the Prince of Hell, the Tempter) performed in three distinctive environments (Heaven, Hell, Earth) and distinguished by three distinctive names (Lucifer, Satan, the Devil).2 Milton’s Satan fulfills these three “roles,” to be sure, but he is distinctly different from his Renaissance forebears, which is in part due to Milton’s storytelling.

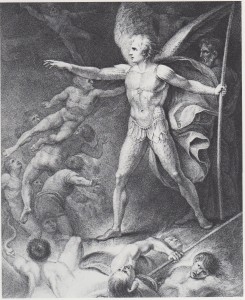

The closest literary relative of Milton’s Satan is the titular angel of Joost van den Vondel’s tragedy Lucifer (1654), so-called because it follows the descent of the Light-Bearer from Heaven, where he cuts a dazzling figure in image and in action, into Hell, where he is humbled—fallen in every sense of the word. Milton’s Paradise Lost, on the other hand, begins in epic fashion in media res (“in the midst of things”), Satan already fallen into Hell. But Milton wanted to portray Satan as superhumanly seductive at the opening of his poem in Books I and II, where he dominates the action, so as to make the reader feel the extent of the power of “the proud / Aspirer” (VI.89–90) whom a third of the heavenly host marched behind into perdition. As a result, Milton wound up producing, as John M. Steadman observes in his essay on “The Idea of Satan as the Hero of Paradise Lost,” Satan the Prince of Hell intermingled with Lucifer the aspiring archangel:

The Satan of the first books of Paradise Lost is, in a sense, a transitional figure between the aspiring rebel against God and the sly seducer of mankind. Milton has left him much of his original brightness and his original archangelic form; and in character and rhetoric, as well as in external shape, he bears a closer resemblance to the hybristic Lucifer of the celestial war than to the Mafia figure he will subsequently become.3

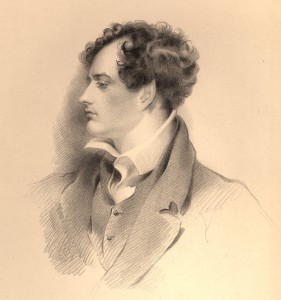

Milton’s “Apostate Angel” (I.125) vastly outshined all prior Satanic models, and Romantic Satanists very much admired the peerless rebel prince introduced in Books I and II of Paradise Lost. William Hazlitt wrote that Paradise Lost’s “two first books alone are like two massy pillars of solid gold,” his idolization of the poem of course the result of its compelling arch-rebel: “In a word, the interest of the poem arises from the daring ambition and fierce passions of Satan.…Satan is the most heroic subject that ever was chosen for a poem; and the execution is as perfect as the design is lofty.”4 Lord Byron asserted in a similar vein that “the two first books of it are the very finest poetry that has ever been produced in this world.”5

The Romantics felt the Satanic Lucifer/Luciferian Satan of Books I and II of Paradise Lost eclipsed the rest of the poem, where the Prince of Hell transitions into his role of Tempter and proceeds “To wreck on innocent frail man his loss / Of that first Battle, and his flight to Hell,” finally becoming “the Devil” (IV.11–12, 502). This gives credence to the position John Carey takes in his essay on “Milton’s Satan”: “The ambivalence of Milton’s Satan stems partly from his trimorphic conception; pro-Satanists tend to emphasize his first two roles, anti-Satanists his third.”6 Perhaps what made Byron most merit the position of “master-Satanist”7 of the Satanic School was his radical choice to take the Miltonic tradition a step further and idealize the Tempter role of the diabolical triptych.

The Lucifer of Byron’s Cain: A Mystery (1821) is clearly cast in the mold of Milton’s Satan, but wrested from the Christian cosmology of Paradise Lost and recast as a rather Promethean figure, however haughty he might be. “I tempt none,” insists the Byronic Lucifer, “Save with the truth” (I.i.196–97). It is certainly a step beyond Shelley, who in the Preface to Prometheus Unbound (1820) deemed Milton’s fallen light-bringer the near-equal of the fire-bringer, Prometheus, but conceded that the fellow God-defying hero Satan fell short of the Promethean ideal.8

Byron’s Promethean purification of the Miltonic Satan involved restoring to the fallen angel Lucifer status—not merely in name but in function. Yet Byron infused the illustrious angelic name he returned to the Devil with Satanic irreverence, for it is not divine radiance that the Lucifer of Byron’s Cain brings, but the enlightenment of a self-assertively godless existence—a true Promethean state indeed. Despite the ambiguity of his disdainfully patrician disposition, Cain’s Lucifer enlightens the Byronic title character by illuminating a path of defiant, liberating godlessness, his parting words of wisdom to Cain transforming the so-called “Fall of Man” into the most profound moment in human history. With overt allusions to “the mind is its own place” speech Milton’s Satan delivers on the burning marl of Hell (I.242–70), Byron’s Lucifer urges Adam’s firstborn son to cast off the tyrannous yoke of divine authority and embrace what the cursed apple of Eden has paradoxically blessed the human race with:

One good gift has the fatal apple given—

Your reason:—let it not be over-sway’d

By tyrannous threats to force you into faith

’Gainst all external sense and inward feeling:

Think and endure,—and form an inner world

In your own bosom—where the outward fails;

So shall you nearer be the spiritual

Nature, and war triumphant with your own. (II.ii.459–66)

Although Cain is no sooner prepared to bend the knee to his father’s Devil than his God (I.i.310–18), and although he pities Lucifer for his loveless aloofness (II.ii.338), Cain admires the rebel angel as a Promethean patron—“A foe to the Most High,” but a “friend to man” (III.i.169). Byron scholar Jerome J. McGann concurs insofar as he finds in Lucifer’s grand concluding speech “a commitment to intellectual freedom that has never been surpassed in English verse.”9

Byron’s Lucifer, in his fierce opposition to Heaven’s “indissoluble tyrant!” (I.i.153), bears a notable resemblance to Milton’s Satan, and Byron openly acknowledges his debt in Cain’s Preface. As Miltonic as Byron’s Lucifer may be, however, he is a rehabilitated Devil in several significant respects.10 The insistence of Byron in the Preface to Cain and of Lucifer in the play itself that the Devil and the Eden serpent are not one and the same both undermines the Christian account of the Fall and exonerates Lucifer from the malevolence towards Man maintained in the Miltonic model. Byron’s restoration of the name Lucifer is emblematic of this rehabilitation, as Peter A. Schock notes in his study of Romantic Satanism: “This defamiliarizing effect is compounded by the use of the angelic name derived from Isaiah [14:12], distancing Lucifer from the New Testament tradition of demonology.”11

The Luciferian Lord Byron’s preference for the Devil’s prelapsarian name was no whitewash. Milton’s Satan, at the end of his journey in Paradise Lost, prides himself on his name “Satan (for I glory in the name, / Antagonist of Heav’n’s Almighty King)” (X.386–87), but if synonymous with the Miltonic Satan’s moniker is his “unconquerable Will” and “courage never to submit or yield” to the God who “Sole reigning holds the Tyranny of Heav’n” (I.106, 108, 124), the Lucifer of Cain is certainly no less Satanic: “I have a victor—true; but no superior. / Homage he has from all—but none from me…” (II.ii.429–30). Byron’s choice of Lucifer over Satan in fact exacerbates rather than evades the element of blasphemous defiance; its implications are far more radical than the impious effort to break Lucifer free from Christian/Miltonic tradition: Lucifer, Byron suggests, is more of a light-bearer in his fallen rather than his unfallen state. In falling from Heaven, the Byronic Lucifer does not lose his honorific, as in Paradise Lost (I.82; V.658–59), but gains it. It is a sentiment captured rather splendidly by the Devil of Glen Duncan’s novel, I, Lucifer: “Ironic of course that after the Fall they stopped referring to me as Lucifer, the Bearer of Light…Ironic that they stripped me of my angelic name at the very moment I began to be worthy of it.”12

Romanticism shed new light on Milton’s Satan, and Romantic Satanism re-envisioned the arch-rebel in a flattering light, so it was perhaps inevitable that Satan would once again become Lucifer. The Latin Lucifer is quite simply far more mellifluous, more elegant, more magisterial than the Hebrew Satan, and therefore an entirely more appropriate moniker for the regal rebel angel out of the Miltonic-Romantic tradition, who lent himself to that refined radicalism of Romantic Satanism. I believe Lord Byron’s Cain to be the apex of Romantic Satanism, and I find it entirely appropriate that when the Miltonic-Romantic Devil reached his zenith, he reclaimed his native name, Lucifer.

Notes

1. Frank S. Kastor, Milton and the Literary Satan (Amsterdam: Rodopi N.V., 1974), p. 15.↩

2. See ibid., pp. 15–16.↩

3. John M. Steadman, “The Idea of Satan as the Hero of Paradise Lost,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 120, No. 4, Symposium on John Milton (Aug. 13, 1976), p. 272.↩

4. William Hazlitt, Lectures on the English Poets (1818), “Lecture III: On Shakespeare and Milton,” in The Romantics on Milton: Formal Essays and Critical Asides, ed. Joseph Anthony Wittreich, Jr. (Cleveland: The Press of Case Western Reserve University, 1970), p. 384.↩

5. Quoted in Martin Garrett, The Palgrave Literary Dictionary of Byron (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), p. 194.↩

6. John Carey, “Milton’s Satan,” in The Cambridge Companion to Milton, ed. Dennis Danielson (New York [2d rev. ed. 1989]: Cambridge University Press, 1999), p. 162.↩

7. Clara Tuite, Lord Byron and Scandalous Celebrity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 233.↩

8. Percy Bysshe Shelley, Preface to Prometheus Unbound, in Shelley’s Poetry and Prose, ed. Donald H. Reiman and Neil Fraistat (New York [2d rev. ed. 1977]: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2002), pp. 206–07: “The only imaginary being resembling in any degree Prometheus, is Satan; and Prometheus is, in my judgement, a more poetical character than Satan because, in addition to courage and majesty and firm and patient opposition to omnipotent force, he is susceptible of being described as exempt from the taints of ambition, envy, revenge, and a desire for personal aggrandisement, which in the Hero of Paradise Lost, interfere with the interest.”↩

9. Jerome J. McGann, ed. Lord Byron: the Major Works (New York: Oxford University Press Inc., [1986] 2008), p. 1072n.↩

10. Milton’s Satan evades the angelic guards of Eden and hides inside the serpent, the slimy vessel within which he laments he must lowly descend for conquest of the world (IX.157–71), whereas Byron’s Lucifer boasts to Cain that he acts within sight of Eden’s angels (I.i.554–56) and derides the notion that a superior spiritual being free to roam the cosmos would covet what little the material world has to offer, let alone in the shape of a material creature (I.i.216–17, 228, 237–45); Milton’s Satan misinterprets the biblical protevangelium (X.494–501), whereas Byron’s Lucifer is an acute scriptural commentator, informing Cain of the immortality of the soul (I.i.103–19, II.i.90–92) and the future incarnation of the Son of God (I.i.163–66, 540–42), theological concepts which Cain, as an Old Testament character, is unaware of; Milton’s Satan boasts of having “by fraud…seduc’d [Man] / From his Creator” (X.485–86), whereas Byron’s Lucifer indignantly insists, “I tempt none, / Save with the truth…” (I.i.196–97).↩

11. Peter A. Schock, Romantic Satanism: Myth and the Historical Moment in Blake, Shelley, and Byron (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), p. 104.↩

12. Glen Duncan, I, Lucifer (New York: Grove Press, 2002), p. 12.↩