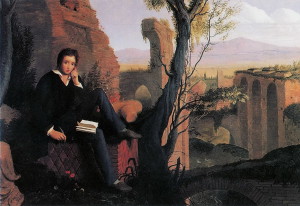

Alongside Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley also possessed a penchant for the Satanic1—arguably more so than “the Satanic Lord.”2 In his study of Romantic Satanism, Peter A. Schock determines “Shelley – not Byron – to be the driving force in the development of the Satanist writing of this group,” for as devilish as Byron’s persona and poetry were, “In adopting the stance of the diabolical provocateur, Byron was led by the precedent of Shelley.”3 It is certainly true that Shelley anticipated Byronic Satanism with his amplification of his own rebellious characteristics through adoption of a devilish persona—less pessimistically than Byron, it must be said—and his employment of grandly Satanic characters in his poetry.

Shelley, the youthful radical expelled from Oxford University for refusal to deny authorship and distribution of a pamphlet on The Necessity of Atheism (1811), entertained fantasies of himself as an ennobled Satanic opponent of the Christian Deity he demonized: “Oh how I wish I were the Antichrist, that it were mine to crush the Demon, to hurl him back to his native Hell never to rise again – I expect to gratify some of this insatiable feeling in Poetry.”4 Shelley echoes Milton’s Satan and his rebel angels, who refer to God with epithets typically reserved for the Devil, such as “enemy” (I.188, II.137) and “foe” (I.122, 179; II.78, 152, 202, 210, 463, 769). Shelley thus exhibits the true nature of Romantic Satanism, which is getting caught up in “Satan’s cult of himself”5 insofar as Romantic Satanists deliberately sided with the Miltonic Satan, accepting Satan’s own lofty image of himself. The Satanic Shelley followed the precedent set by his mentor and eventual father-in-law, William Godwin, whose analysis of Milton’s Satan in his radical Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793) more or less took Satan at his word: “But why did he rebel against his maker? It was, as he himself informs us, because he saw no sufficient reason, for that extreme inequality of rank and power, which the creator assumed.”6

The would-be Antichrist Shelley’s insatiably deicidal desires were certainly gratified in his poetry. In Queen Mab (1813), Shelley invoked the mythic “Wandering Jew” Ahasuerus, transforming the doubting Semite into an idealized Satanic blasphemer, who channels the spirit of Milton’s Satan in his defiance of the tyranny of Heaven (VII.173–201). In the Preface to Prometheus Unbound (1820), Shelley went so far as to deem Satan the near-equal of that ultimate Romantic symbol of boundless human potential imprisoned within the bonds of divine oppression, Prometheus: “The only imaginary being resembling in any degree Prometheus, is Satan.…the Hero of Paradise Lost…”7

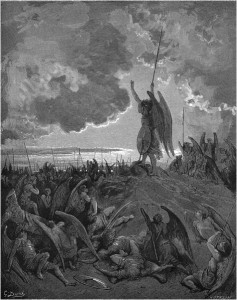

Shelley employed Satanism not only as a means of dramatically expressing his contempt for Christianity, but also for a more positive expression: admiration for the unfettered humanity he so longed for. The dramatic finish to Shelley’s Declaration of Rights (1812)—a clarion call for Man to assert his proper worth and rise from lowliness and degeneracy to loftiness and dignity—reads, “Awake!—arise!—or be forever fallen,”8 which is the concluding line of the fiery speech with which Milton’s Satan rouses his fallen compatriots from the burning lake of Hell (I.330). Shelley thus casts himself as Milton’s Satan, whose “heart / Distends with pride” at the sight of his fallen but reassembled brethren, who are promised, “this Infernal Pit shall never hold / Celestial Spirits in Bondage…” (I.571–72, 657–58). In the closing diatribe of A Declaration of Rights, the pride in Man’s innate dignity and lofty potential Shelley expresses is intermingled with scorn for his current state of abjection, Shelley thus attempting to awaken Man in the same way that Milton’s Satan summons his fallen legions (I.315–23). Shelley adopted the persona of the Miltonic Satan, who believes himself a noble liberator, whose supporters were “freed / From servitude inglorious” (IX.140–41) by him, a “faithful Leader” (IV.933) at whose resumed command “Celestial Virtues rising, will appear / More glorious and more dread than from no fall…” (II.15–16).

Shelley’s acceptance of Satan’s self-image and his willingness to incorporate the idealized Satanic spirit into his own self-dramatization verifies Southey’s claim that the members of the Satanic School were essentially among Satan’s number. Despite the lack of belief of Byron and Shelley—more prominently pronounced in the latter—it is easy to imagine them enlisted in the rebel archangel’s “Satanic Host” (VI.392), beneath “Th’ Imperial Ensign” passionately “Hurling defiance toward the Vault of Heav’n” (I. 536, 669).

Notes

1. See Ann Wroe, Being Shelley: The Poet’s Search for Himself (New York: Vintage Books, [2007] 2008), pp. 319–22.

↩

2. Mario Praz, The Romantic Agony, trans. Angus Davidson (Cleveland and New York: The World Publishing Company, [1933] 1963), p. 81.↩

3. Peter A. Schock, Romantic Satanism: Myth and the Historical Moment in Blake, Shelley, and Byron (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), pp. 7, 8.↩

4. Quoted in Schock, p. 80.↩

5. Schock, p. 39.↩

6. Quoted in Schock, p. 1; my emphasis.↩

7. Percy Bysshe Shelley, Preface to Prometheus Unbound, in Shelley’s Poetry and Prose, ed. Donald H. Reiman and Neil Fraistat (New York [2d rev. ed. 1977]: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2002), pp. 206–07.↩

8. Percy Bysshe Shelley, A Declaration of Rights, in Shelley’s Prose: or the Trumpet of a Prophecy, ed. David Lee Clark, pref. Harold Bloom (New York: New Amsterdam Books, 1988), p. 72.↩