Milton’s Paradise Lost as an SNES (Super Nintendo Entertainment System) RPG (Role-Playing Game)—that is what the music video for English electronic duo Delta Heavy’s “White Flag” delivers. The Super Nintendo-style video for “White Flag”—a track off of Paradise Lost, Delta Heavy’s debut album of 2016—was directed by Najeeb Tarazi, who had previously worked as a technical director on Pixar blockbusters Toy Story 3 and Monsters University. Tarazi’s vision for the “White Flag” video was inverting the Miltonic treatment of the fall of Lucifer: “ ‘White Flag’ is about letting your guard down in love…I wanted to try turning the myth of Paradise Lost on its head and tell a story where Satan apologizes after his defeat and seeks a path of love. In reply to Satan’s apology, God brutally punishes Satan again.”

Milton’s Paradise Lost as an SNES (Super Nintendo Entertainment System) RPG (Role-Playing Game)—that is what the music video for English electronic duo Delta Heavy’s “White Flag” delivers. The Super Nintendo-style video for “White Flag”—a track off of Paradise Lost, Delta Heavy’s debut album of 2016—was directed by Najeeb Tarazi, who had previously worked as a technical director on Pixar blockbusters Toy Story 3 and Monsters University. Tarazi’s vision for the “White Flag” video was inverting the Miltonic treatment of the fall of Lucifer: “ ‘White Flag’ is about letting your guard down in love…I wanted to try turning the myth of Paradise Lost on its head and tell a story where Satan apologizes after his defeat and seeks a path of love. In reply to Satan’s apology, God brutally punishes Satan again.”

The video for “White Flag” starts with an unmistakably SNES-style title screen, and once the unseen “player” starts the pretend Super Nintendo game, we open to a cherubic (albeit bat-winged) Satan—with curly golden locks and a toga—lying prostrate on Hell’s lake of fire, just as we first see Milton’s Satan in Paradise Lost. In this video(game), Satan soon awakens and takes flight across the lake of fire, which is littered with his fellow fallen angels. Magma erupts like rising pillars toward the sulfurous sky, wherefrom more angels haplessly descend like meteorites. Before long, Satan gracefully lands in front of the gates of Hell (a simple sign replacing Sin and Death in this version), and he is soon approached by his second-in-command, Beëlzebub, who is here imagined as a cartoonish, somewhat Lovecraftian “Lord of the Flies.” This buzzing Beëlzebub speaks to Satan in the simple dialogue familiar to SNES games: “SATAN! Only you can save us. Defeat GOD.” With that, Satan “Springs upward like a Pyramid of fire” (PL, II.1013) through the smoke-clouds of Hell and starts his journey through the cosmos (in this case, skipping over the difficult course through Chaos).

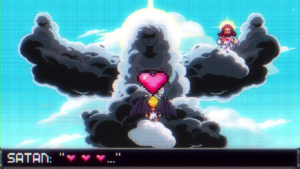

Satan darts past the Earth and, with fierce determination in his bright red eyes, heads toward a cosmic chasm, through which Satan enters into Heaven (the steps of which Satan stops at in Paradise Lost [III.498–543]). Satan confidently wings his way up to a cloud, and though he wields a spear, Satan passively takes the blows as he is stormed by a swiping flight of hostile cherubs. The video gives the impression that, as an RPG, the player is given options: “FIGHT,” “RUN,” “APOLOGIZE.” As Almighty God—uniquely portrayed as a cloudy matriarch—descends from up above, Satan chooses to apologize, but he is met with further hostility by the archangel Michael and the Son of God, with amusing messages to the “player”: “GOD summons MICHAEL!” and “JESUS casts LIGHTNING II!” Satan retaliates with only a bright pink cartoon heart that appears above his head. God and His/Her Son disappear, however, and the heart hovering over Satan’s head is replaced by a question mark. As the song’s beat drops, Satan is repeatedly shanked by a titanic hand thrusting down from above, the apologetic angel screaming out in unimaginable pain. Satan collapses onto his cloud, and is soon unceremoniously dumped out of Heaven by two cherubs.

Satan darts past the Earth and, with fierce determination in his bright red eyes, heads toward a cosmic chasm, through which Satan enters into Heaven (the steps of which Satan stops at in Paradise Lost [III.498–543]). Satan confidently wings his way up to a cloud, and though he wields a spear, Satan passively takes the blows as he is stormed by a swiping flight of hostile cherubs. The video gives the impression that, as an RPG, the player is given options: “FIGHT,” “RUN,” “APOLOGIZE.” As Almighty God—uniquely portrayed as a cloudy matriarch—descends from up above, Satan chooses to apologize, but he is met with further hostility by the archangel Michael and the Son of God, with amusing messages to the “player”: “GOD summons MICHAEL!” and “JESUS casts LIGHTNING II!” Satan retaliates with only a bright pink cartoon heart that appears above his head. God and His/Her Son disappear, however, and the heart hovering over Satan’s head is replaced by a question mark. As the song’s beat drops, Satan is repeatedly shanked by a titanic hand thrusting down from above, the apologetic angel screaming out in unimaginable pain. Satan collapses onto his cloud, and is soon unceremoniously dumped out of Heaven by two cherubs.

Falling back through the chasm into the cosmos, the unconscious Satan tumbles through the stars like a piece of fruit falling through the branches of a tree. Back in Hell, Beëlzebub pokes through Hell’s clouds to see Satan streaking through the starry sky like a comet. A wide shot of the Earth then shows Satan’s descent through a shaft of light. Now in the Garden of Eden, we see Satan crash-land face-down—not unlike how he started on Hell’s lake of fire—and while the only option the “player” now seems to have is to “DIE,” two shadowy figures (surely Ben Hall and Simon James of Delta Heavy) from behind the bushes toss Satan an apple, the fallen angel transforming into a sort of “Super-Satan,” with red skin, bulging muscles, flaming hair, and horns. Turning his determined gaze heavenward, Satan re-ascends back through the shaft of light. Back in Heaven, Satan—hell-bent on gaining God’s forgiveness—clinches the Son in his arms, transforming back into (fallen) angel form, and the Son’s face appears just as pained as Satan’s when he felt the wrath of God moments earlier. This time, a cataract descends from God’s cloudy throne through the chasm and out into the cosmos. In the Garden of Eden, the rainfall makes the infamous apple drop down onto the Eden serpent’s head—symbolic, perhaps, of this revision excising that portion of the story, Satan having turned over a new leaf. As flowers begin to sprout up amidst the arid soil of Hell, courtesy of the heavenly rainfall, Satan lands back in front of Beëlzebub, no dialogue exchanged between the two. The video then ends with a shot of the Milky Way, with a cartoon heart at its center, as the “game” announces to the “player,” “GAME OVER.”

The “White Flag” video starts and ends like a Super Nintendo game, but while this 16-bit reimagining of Milton’s Paradise Lost shares a very similar opening to the poem, the ending is entirely different. While, of course, Tarazi nods to the tradition of Satan’s salvation and reconciliation with the Almighty—more popular with the French Romantics1—the conclusion to this video is a bit more ambiguous. In the end, Satan and Beëlzebub still appear fallen (Beëlzebub undeniably so). If this were a Super Nintendo game, this could be explained away by an inability to create any more sprites given the limited memory of the 16-bit system. This is not an SNES game, however; so what might the significance of the ending be? In Paradise Lost, when Satan sets foot on Earth and observes the glory of the Sun, which brings back the bitter memory of his former state, forever forfeited by his rebellion (IV.9–41), Satan contemplates the thought of repentance, ultimately rejecting the idea because he knows his pride would compel him to challenge the Almighty all over again (IV.79–102). God, Satan concludes, as “punisher” is “as far / From granting…as I from begging peace” (IV.103–04), and so “All hope [is] excluded…” (IV.105). The Christian tradition has always identified an element of pride in such despair, however, as people who believes themselves irredeemable essentially state that not even God Himself can save them, which is a curious assertion of superiority to the Almighty. Tarazi seems to turn this on its head, showing a Satan strong enough to force Almighty God to forgive him after a futile attempt at apologizing. After all, Tarazi’s explanation of his vision for the video makes no hint of God actually accepting Satan’s apology: “…Satan apologizes after his defeat and seeks a path of love. In reply to Satan’s apology, God brutally punishes Satan again.”

The God Tarazi describes is reminiscent of the Romantic view of God as omnipotent tyrant, and in turn Tarazi’s Satan, imagined as a fallen but forgiving angel, resembles Shelley’s Prometheus in Prometheus Unbound (1820). Whereas Byron’s vision of the Titan in his poem “Prometheus” (1816) was one of noble defiance of despair—much like the Lucifer of his Cain (1821), who “Prefer[s] an independency of torture / To the smooth agonies of adulation” (I.i.385–86)—Shelley envisioned a Prometheus who repents of his hatred for his oppressor, Jupiter. It is this Promethean power of universal love that leads to the tyrant’s overthrow and the ushering in of Shelley’s vision of a cosmic utopia.

While clearly not the arch-rebel of the Miltonic-Byronic tradition, the Satan of the video for Delta Heavy’s “White Flag” seems closer to Shelley’s scenario of the loving prisoner overcoming the coldhearted torturer than a reconciliation of God and the Devil. In short, Satan is triumphant, but he triumphs because he overcomes his hatred for the cruel God, thereby introducing love rather than chaos into the cosmos. Therefore, this cartoonish, Super Nintendo Satan, ironically enough, makes for an interesting fusion of the Romantic Satan and Prometheus.

Notes

1. See Maximilian Rudwin, The Devil in Legend and Literature (LaSalle, IL: Open Court Publishing Company, [1931] 1959), Ch. XXII, “The Salvation of Satan in Modern Poetry,” pp. 280–308; Jeffrey Burton Russell, Mephistopheles: the Devil in the Modern World (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, [1986] 1990), pp. 194–200; Ruben van Luijk, Children of Lucifer: The Origins of Modern Religious Satanism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 74–76, 105–08.↩