Milton’s Satan was at his most celebrated during the Romantic era, and so it is only appropriate that we find in Romantic artwork the Miltonic arch-rebel’s pictorial apotheosis. By the close of the eighteenth century, Milton (sans his revolutionary republicanism) was seen alongside Shakespeare as a cultural pillar of Britain, and with the advent of major artistic institutions—most significantly the Royal Academy of Arts, founded in 1768 with the patronage of George III—there was ever greater emphasis on the creation of British artwork in what Sir Joshua Reynolds, the Royal Academy’s first President, called “the Grand Style.” Such sublime artwork, which was designed to equal that of the continental Old Masters, would not only elevate the prestige of the national identity, but that of the artists themselves. In this age of the artist as hero, British painters and draftsmen journeyed to Rome, the cultural epicenter of Europe, to study the masterpieces of classical antiquity and the Renaissance, finding inspiration for their own ambitious attempts at history painting—the most exalted artistic genre, depicting heightened narrative moments drawn from works of high culture, such as classical mythology and history, the Bible, Shakespeare, and, of course, Milton.

Like Shakespeare, Milton was of particular importance to the eighteenth-century British art world because he embodied an ideal of British creative liberty, having flaunted convention in his own work. (Paradise Lost, like the classical epics, does not rhyme.) And while Milton the cultural icon had been stripped of the political radicalism of Milton the man, Miltonic revolutionism permeates Paradise Lost’s blank verse structure, which the regicide-supporting Milton defended as “ancient liberty recover’d to Heroic Poem from the troublesome and modern bondage of Riming.” This political component was not lost on the artists of the revolutionary era of the 1790s, who rendered Milton’s Satan—the “Antagonist of Heav’n’s Almighty King” (X.387)—as a handsome and heroic arch-revolutionary, a Promethean figure who meets his cataclysmic fall from Heaven with dauntless defiance. The Romantic Satan reflects other social tensions as well, namely the anxiety over the growing mobility and status of women in society, and, it was feared, the attendant emasculation of men. “In an age of luxury,” the Swiss-born Henry Fuseli wrote, “women have taste, decide and dictate; for in an age of luxury woman aspires to the function of man, and man slides into the offices of woman. The epoch of eunuchs was ever the epoch of viragos.” Romantic history painting—not least Fuseli’s—was in part a response to this, producing hyper-masculine, superhuman heroes in an aggressive reassertion of threatened masculinity. These idealized male nudes had a paradoxical effect, however: the male form had become, like the female form, eroticized. (See Martin Myrone, Bodybuilding: Reforming Masculinities in British Art 1750–1810.) The Romantic vision of Milton’s Satan—sometimes visualized as wingless and therefore wholly human—highlights this paradox: while Satan is titanic in stature and the masculine musculature of his often nude athletic form is ennobled—a visual anticipation of French Decadent poet and essayist Charles Baudelaire’s assertion that “the most perfect type of male beauty is Satan as depicted by Milton”—there is more than a trace of the feminine in the fallen angel, as he is notably beautiful, his movement graceful. It has been observed, for instance, that Fuseli’s Satan appears to be a hermaphroditic union of the artist’s heroically conceived Death and sensually conceived Sin, and similar androgyny is discernible in almost all of the Romantic representations of the Miltonic Satan. (This is one of a number of parallels between Milton and his creation, as during his time at Christ’s College, Cambridge, Milton was known to his peers as “The Lady of Christ’s” on account of his effete features.)

All in all, Milton’s Satan was a perfect figure for British Romantic artists’ aspirations to the Grand Style: Paradise Lost was the greatest English epic poem; the fallen angel Satan, whom Milton heaped classical magnificence upon, was undeniably its grandest character; and the Hell-doomed arch-rebel was a means of expressing pictorially the sociopolitical turbulence of the day. For all of these reasons, what emerged from Romanticism’s Miltonic iconography was nothing less than the most idealized imagery of the fallen archangel—and, it must be said, the most accurate portrayal of the majestic rebel who curiously holds pride of place in Paradise Lost. “As to the Devil he owes everything to Milton,” observed Percy Bysshe Shelley in his unpublished Essay on the Devil and Devils (ca. 1819–20), for “Milton divested him of a sting, hoofs, and horns, clothed him with the sublime grandeur of a graceful but tremendous spirit—and restored him to the society.” Shelley’s assessment is astute, for Milton broke radically from Christian tradition with Paradise Lost’s exceedingly generous portrait of the fallen angel, and it was only Romantic artwork that came close to appreciating this. A telling example: a Guide to the Exhibition of the Royal Academy of 1797 remarked of Sir Thomas Lawrence’s Satan Summoning His Legions—arguably the most idealized of Romantic art’s Miltonic Satans—that it did not quite depict Milton’s Satan alluringly enough: “The figure of Satan is truly sublime…Perhaps somewhat less of distortion in the countenance of the arch fiend would have been more according to Milton’s description of him.”

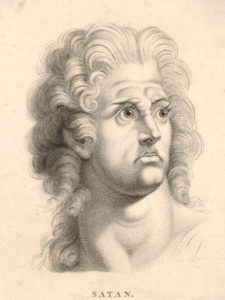

It is indeed difficult to overemphasize just how singularly sublime Milton’s Satan is presented in Paradise Lost. Traditionally, the luminous angel Lucifer became darkened and deformed in his descent from Heaven into Hell, but in the underworld of Paradise Lost, Milton’s Satan cuts a truly dazzling figure: firmly gripping his ponderous shield and mast-like spear (I.284–96) like a classical hero, the fallen archangel, with his “mighty Stature” (I.222), stands “above the rest / In shape and gesture proudly eminent / …like a Tow’r…” (I.589–91). Milton’s repeated reassurance that Satan’s “form had yet not lost / All her Original brightness, nor appear’d / Less than Arch-Angel ruin’d” (I.591–93) demonstrates that the poet’s “Prince of Darkness” (X.383) is not nearly as darkened as he might have been; indeed, Paradise Lost pictures Satan as the Sun obscured by a misty horizon or eclipsed by the Moon (I.592–99)—“Dark’n’d so, yet shone / Above them all th’ Arch-Angel…” (I.599–600). As the prestigious Miltonist John Leonard puts it, “Satan is a ‘disstarred’ Lucifer…He is not the prince of darkness, but the prince of twilight, a denizen of Heaven, splendid even in exile” (The Value of Milton, p. 75). This Miltonic makeover of Satan as fallen Lucifer is precisely what Romantic artists executed as they brought the princely rebel angel to life. The Romantic Satan is heroically human, his form—almost always angel-winged, if not wingless and fully humanized—titanic in stature, his face Apollonian in beauty, with due emphasis on Milton’s description of “Eyes / That sparkling blaz’d” beneath “Brows / Of dauntless courage, and considerate Pride…” (I.193–94, 602–3). As Romantic Satanic artwork discards traditional Christian iconography in favor of Milton’s poetry, long gone are the bestial horns and hoofs and general grotesquerie of medievalism; the Miltonic Satan of Romanticism is clothed in a splendor befitting a Grecian god.

The importance of the images of Satan which appear across Romanticism’s Miltonic iconography simply cannot be overstated. Those who never venture to read Paradise Lost’s more than ten thousand lines of verse (“None ever wished it longer,” Samuel Johnson famously remarked) or the Romantics’ extensive critique of Milton’s epic poem, to say nothing of their own Satanic poetry and prose, can still comprehend the Miltonic-Romantic legacy of Lucifer simply by surveying the abundant sketches, paintings, and engravings of Romantic illustrators of Milton. Gazing upon the Romantic Satan is the simplest way to understand just how illustrious Lucifer was during Romanticism—but to also understand that, as Shelley duly noted, the Devil is indebted not so much to the Romantics as to Milton, whose Paradise Lost invited—or rather insisted upon—such a reimagining.

Henry Fuseli (1741 – 1825)

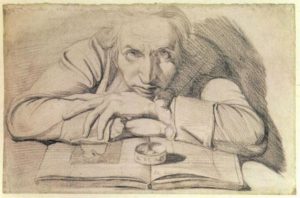

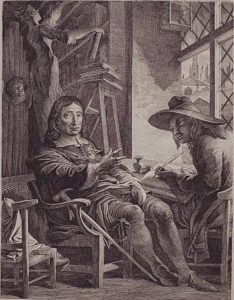

Fuseli was one of the great cultural enigmas of the Romantic era, responsible for some of the most recognizable imagery of Romanticism, such as the Gothic triumph with which he made his name: The Nightmare (1781). The Swiss-born Johann Heinrich Füssli, though belonging to a family of artists, was put on a seminary path by his father. During his time at the intellectual and cultural beacon that was Zurich’s Collegium Carolinum, however, Fuseli was introduced to Milton’s Paradise Lost by Johann Jakob Bodmer (1698–1783), the luminary who authored the German prose translation of the epic poem published in 1732, and thus instilled in Fuseli a lifelong fascination with Milton (as well as Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, and others). Fuseli became an ordained Zwinglian minister in 1761, but for his part in exposing a corrupt magistrate the following year, Fuseli was compelled to flee from his native Switzerland, whereat he embarked on a literary and, more importantly, an artistic journey for the remainder of his life. Fuseli wandered abroad for some time, most importantly in Rome, as suggested to him in London by Sir Joshua Reynolds, President of the Royal Academy. “Here is something for my self-regard,” Fuseli wrote to his close friend Johann Caspar Lavater (1741–1801) in 1768, “Reynolds tells me that I will be the greatest painter of the age, if I can only spend a few years in Rome.” His stay was to be eight years (1770–1778), after which Fuseli ultimately settled in London, where he would become involved in the Johnson Circle, the intellectual group presided over by radical publisher Joseph Johnson (1738–1809), which included the likes of anarchist author William Godwin (1756–1836), feminist pioneer Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797)—who aggressively pursued Fuseli until Mrs. Fuseli forbade her from their home—revolutionist Thomas Paine (1737–1809), and mystic poet and artist William Blake (1757–1827). Though a cultural outsider who scorned the British art establishment, Fuseli was nevertheless elected an Associate Member of the Royal Academy in 1788, full Academician in 1790, and was eventually appointed by the RA as Professor of Painting in 1799 (replacing James Barry, who had been expelled) and later Keeper in 1804. Thus, the artist who was widely seen as eccentric and even borderline mad was not only accepted into the establishment, but ultimately put in a position whereby he would influence a generation of British artists.

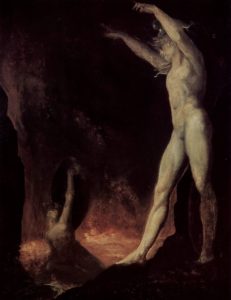

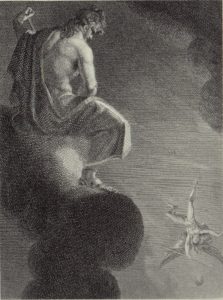

Fuseli, a painter of the proto-Romantic Sturm und Drang (“Storm and Stress”) movement, had an extraordinarily distinct style—pushed to an extreme in the competitive climate of Rome, overcrowded as it was by ambitious British artists vying for patronage—and the heroic figures of Fuseli’s wild artwork, which was at its best in the artist’s treatment of supernatural subjects, are all gigantically imagined: elongated limbs, exaggerated musculature, and violently melodramatic poses. The Satan of Milton’s Paradise Lost was the perfect figure for Fuseli’s art style, and so the ambitious painter and draftsman became Romanticism’s most prolific illustrator of the Miltonic Satan, proving profoundly influential on the depictions of Milton’s Satan sketched, painted, and engraved by the artist’s contemporaries. In the same year John Robert Cozens painted his Satan Summoning His Legions (1776)—the most notable forerunner to Romantic Satanic iconography—Fuseli was in Rome sketching scenes from Paradise Lost with a heroic and handsome Satan at their center, scenes which he would later flesh out into full-fledged paintings for his Milton Gallery (1799, 1800). Following his contributions to the Shakespeare Gallery (1789–1805)—the grand English endeavor for which the entrepreneurial John Boydell (1720–1804) assembled a panoply of Britain’s finest artists to create—Fuseli, with a Luciferian kind of ambition, sought to single-handedly create an accompanying Milton Gallery, an aspiration for which he spent nine years (1790–1799) painting some forty epic canvases to realize.

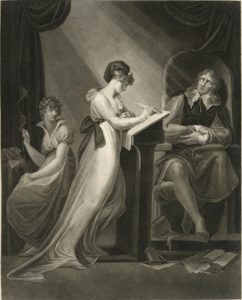

Fuseli’s Milton Gallery was originally intertwined with a Johnson project: a lavishly illustrated folio edition of Milton, which would be edited by William Cowper (1731–1800), illustrated by Fuseli (thirty illustrations in all), and published by Johnson. The project was abandoned by Johnson on account of the decline of Cowper’s mental health, and Fuseli moved on to his work on the Milton Gallery alone. Scenes from Paradise Lost made up the vast majority of paintings (twenty-seven, to be exact) for Fuseli’s ill-fated Milton Gallery, and the figure dominating these pieces was none other than Satan. “Our friend Fuseli is going on with more than usual spirit,” Wollstonecraft observed in a letter composed during the artist’s work on the Milton Gallery paintings, adding, “like Milton he seems quite at home in hell – his Devil will be the hero of the poetic series…” Indeed he was: Milton’s Satan emerges from Fuseli’s dramatic artwork as a wholly humanized and heroic figure, beautiful and brave. Fuseli’s Satan is imagined as a Homeric hero; the pose of the protagonists of Fuseli’s Satan calling up his Legions (1802) and an Achilles (1815) sketch is exactly the same, and a great deal is said by the most Homeric Milton Gallery painting: Odysseus between Scylla and Charybdis (1794–96). In Paradise Lost, Milton invokes this scene as an analogue to Satan’s arduous journey through the realm of Chaos, which Milton emphasizes is in fact far more arduous than that of Odysseus, as well as that of Jason and the Argonauts (II.1010–22); the same effect is accomplished by this painting’s place in the Milton Gallery, as Fuseli’s Miltonic Satan vastly outshines his Homeric Odysseus.

Fuseli undoubtedly conceived the character of Milton’s Satan as an embodiment of the unfettered human spirit, defiant in the face of despair. From his time as a student of theology in Zurich, Fuseli was a close friend of the aforementioned Lavater, who was a proponent of physiognomy—the quasi-science that holds character traits can be deduced from facial features—and Fuseli lent much assistance to Lavater’s Physiognomical Fragments, providing illustrations for the German edition (1775–78), the French edition (1781–87), and helping with the translation of the three-volume English edition (1789–98) published by Johnson. Fuseli’s physiognomical contribution representing “heroic pride” was a Head of Satan (see Peter Tomory, The Life and Art of Henry Fuseli, pl. 168), and while this overwrought image is by no means Fuseli’s best representation of Milton’s Satan, it serves as an explicit statement on how the artist saw the Hell-doomed anti-hero. “Fuseli, never one for not going to extremes,” writes cultural critic Marina Warner, “extends the Lavater system, and offers the whole body as a seismograph of the volcanic eruptions surging inside” (“Invented Plots: The Enchanted Puppets and Fairy Doubles of Henry Fuseli,” in Gothic Nightmares: Fuseli, Blake and the Romantic Imagination, ed. Martin Myrone, p. 26); the striding, bounding, and flying figure of Satan that bursts out of Fuseli’s Paradise Lost paintings magnifies the artist’s sense of his heroic pride tenfold. “Fuseli was trained in youth to be a Zwinglian minister,” observes British art historian Marcia R. Pointon, “yet in the pictures he painted for the Milton Gallery his rejection of God is total and complete.…Satan is the subject of the Milton Gallery, and not Milton’s Satan inhabiting the ordered, meticulously described cosmos of Paradise Lost, but Fuseli’s Satan, the independent, heroic, threatening symbol of the age, existing in a terrifying featureless void” (Milton & English Art, p. 95).

Despite Fuseli’s monomaniacal commitment, the Milton Gallery was a commercial failure. Opening in Pall Mall on the 20th of May in 1799, Fuseli was forced to close the gallery down by the 29th of August. The Milton Gallery was reopened on the 21st of March the following year, with several additional paintings by the artist and a special dinner hosted by the Royal Academy to promote the endeavor, but Fuseli was met with repeated failure, closing the gallery down for a second time on the 18th of July. Fuseli sold many of the Milton Gallery pieces to well-to-do friends to pay off the debts he had accumulated over the decade spent on this project, and a great deal of the paintings are regrettably lost to us. There are various explanations accounting for the lack of success of Fuseli’s Milton Gallery, but perhaps the largest contributing factor was its difficulty to digest for non-Milton scholars. Though he was driven to taking opium to calm his nerves over the project’s uncertain fate, Fuseli perhaps knew deep down that his was a commercial gallery not meant for the masses. Consider the following amusing but telling Milton Gallery anecdote related by Fuseli biographer John Knowles in his three-volume The Life and Writings of Henry Fuseli (1831): “On one occasion, a coarse-looking man left his party, and coming up to him, said, ‘Pray, Sir, what is that picture?’ Fuseli answered, ‘It is the bridging of Chaos: the subject from Milton.’—‘No wonder,’ said he, ‘I did not know it, for I never read Milton, but I will.’—‘I advise you not,’ said Fuseli, ‘for you will find it a d__d tough job’ ” (vol. 1, p. 236). While Fuseli may have wished to seize glory for himself by bringing to life Milton’s poetry—and specifically Milton’s sublime Satan—in a series of epic canvases, I believe the artist was ultimately drawn to the task regardless of its fate. After all, Fuseli returned to illustrating Paradise Lost only two years after the Milton Gallery flop, his paintings to be engraved for F. J. Du Roveray’s small-scale, two-volume edition of Paradise Lost in 1802. There was profound irony in Fuseli’s grand Miltonic ambitions and the resultant titanic Satan ultimately ending up reduced to this diminutive form—these six small engravings a far cry from the lavishly illustrated edition of Milton planned with Johnson more than a decade prior—but again it seems as though the artist felt fated to continue working on Miltonic subjects; indeed, near the end of his life, around 1819–21, Fuseli produced yet two more Paradise Lost illustrations, returning to the characters from the epic poem who first inflamed his imagination in Rome: Satan, Sin and Death.

To his nickname “Painter in ordinary to the Devil,” Fuseli responded warmly, “Aye! he has sat to me many times,” and in the end Fuseli’s Satan was to Romanticism’s Miltonic iconography what Milton’s Satan was to Romanticism as a whole. Fuseli’s work on the Milton Gallery spanned the 1790s, the decade that would see Romantic artists follow Fuseli’s lead and produce the most magnificent depictions of the Miltonic Satan. Undoubtedly, Fuseli, his Milton Gallery, and its Satan were tremendously inspirational to the artist’s contemporaries, namely Barry, Westall, Lawrence, and Blake. While the Milton Gallery may have been a doomed endeavor, its ambitious artist and his heroic Satan were successful—“Successful beyond hope” (PL, X.463), to borrow Satan’s phrase—in establishing Milton’s fallen archangel as a glorious figure of a heroic pride defiant of a dreadful fate, which is to say, a quintessentially Romantic figure.

Thomas Stothard (1755 – 1834)

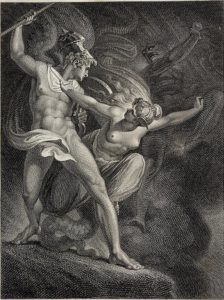

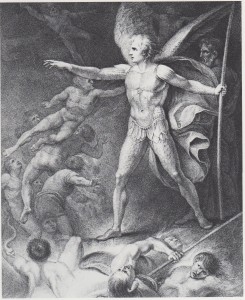

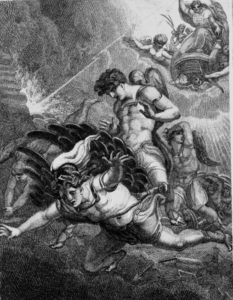

Stothard was an English painter, engraver, and book illustrator. He became a student of the Royal Academy in 1778, was elected an Associate Member in 1792, Royal Academician in 1794, and was later appointed the institution’s Librarian in 1812. Stothard’s Satan Summoning His Legions (ca. 1790) arrived just in time for the foundational years of Romantic Satanism, when English radicals such as Wollstonecraft and Godwin would begin expressing the idea of Milton’s heroic and sublime Satan as a vehicle for challenging oppressive sociopolitical orthodoxies. The only similar work preceding Stothard’s Satan Summoning His Legions was Fuseli’s Satan Starts at the Touch of Ithuriel’s Spear (1779), which Fuseli first sketched in 1776 during his extended stay in Rome and exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1780. Stothard’s Satan, unlike Fuseli’s, is clothed, and while other artists who chose to clothe Satan opted for essentially Roman attire—muscle cuirass and flowing skirt, which Stothard adopts only in his treatment of Pandemonium, wherein a wingless Satan appears as a grand orator—the Satan of Stothard’s designs dons glittering, full-body, scaly armor. Satan Summoning His Legions is the most significant of Stothard’s Paradise Lost illustrations, and while Stothard clearly differentiates the Devil, who dominates almost the entire canvas, from his surrounding associates, Stothard’s Satan is not outsized in the way Lucifer would be pictured by Fuseli, Barry, Westall, and Lawrence. Nevertheless, the significance of Stothard’s Satanic designs is that the Devil appears as a handsome and heroic figure—a fallen angel who even retains his angelic wings. These, of course, are features which would predominate Romantic Satanic artwork.

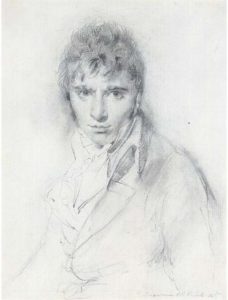

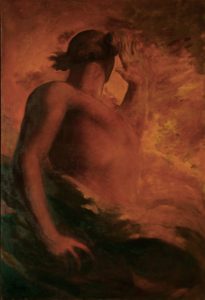

James Barry (1741 – 1806)

Barry was an Irish-born history painter whose view of his life’s work can only be described as mythic. To Barry, the execution of historical subjects was a matter of national significance: “History painting and sculpture should be the main views of every people desirous of gaining honour by the arts,” Barry argued in An Inquiry into the Real and Imaginary Obstructions to the Acquisition of the Arts in England (1775), “tests by which the national character will be tried in after ages, and by which it has been, and is now, tried by the natives of other countries.” This sentiment exalted the artist to heroic heights, and Barry embraced the artist-as-hero role, with all of its dogged endurance of suffering, which his own obstinate and pugnacious personality courted. While he was characterized by a profound persecution complex, to Barry this came with the territory, for the artist saw that men of genius throughout mythology and history incited the resentment and opposition of lesser men; greatness therefore demanded great suffering, and there was no amount of pain and strife Barry was not willing to endure in his pursuit of personal and cultural greatness—as illustrated by the many self-portraits he executed throughout his career, which document the decline of his well-being.

Barry was convinced he was destined to become a great artist from youth, insisting that his father permit him to pursue such a career, and the aspiring artist proved to be a prodigy. Barry’s masterful artwork much impressed Edmund Burke (1729–1797), who authored the text on the sublime, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757), and Barry earned not only Burke’s respect but his patronage, with which the artist was able to spend the years 1765–1771 on the Continent, not least spending four years (1766–1770) in Rome studying the artistic genius of the classical world and the Renaissance Old Masters. Returning to London in 1771, Barry enjoyed a meteoric rise, exhibiting fifteen works at the Royal Academy by 1776. In 1777, Barry was commissioned to paint The Progress of Human Culture, a cycle of six massive canvases for the Great Room of the Royal Society of Arts, which he completed in 1783. For this magnum opus, Barry chose to receive little compensation—and therefore live austerely—on the condition that he be given complete creative control, which gives one a sense of the artist’s commitment to his work. An Associate Member of the Royal Academy by 1772 and elected full Academician shortly thereafter the following year, Barry would later be appointed Professor of Painting to the RA in 1782. However, in 1799 Barry earned the distinction of becoming the only artist (at least until 2005) to be expelled from the Royal Academy, principally for his public criticism of the institution and its members (A Letter to the Dilettanti Society, 1798), but his “democratical opinions” and republican sympathies were almost certainly contributing factors. Barry spent the remainder of his life in increasing isolation, paranoia, destitution, and austerity, reaching his artist’s martyrdom in 1806.

Like many of his contemporaries, Barry viewed his own personal and political tribulations through the lens of Milton: the creative genius beset by envious enemies, who retains a singular dignity in the face of crushing opposition and despondency. Barry likewise harbored profound admiration for Milton the poet, expressing in his Inquiry that Milton “was the first man of genius who was able to make any poetical use (that was not more ridiculous than sublime) of the great personages and imagery of our religion…” For example, whereas Dante, Raphael, and Michelangelo “have painted Satan, according to the old woman’s conception of him, with horns and claws,” Barry observed, “Milton’s touches of character are of a nobler and more spiritual kind.” That is precisely how Barry brought Satan to life in his series of Milton illustrations, which were incited by the Miltonic aspirations of his peers spanning the 1790s, namely Fuseli’s Milton Gallery, which the Swiss-born artist began work on in 1790 and opened nine years later, albeit to public indifference. While British patriotism was a strong impetus for illustrating Milton in the late eighteenth century—as it was for illustrating Shakespeare (the Milton Gallery was Fuseli’s single-handed attempt at emulating Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery)—“at a time of an exciting political revolution on the Continent,” Barry scholar William L. Pressly observes, “Milton’s portrayal of Satan as a spirited rebel against an overpowering hierarchy gave this work an added luster,” and this is reflected in Barry’s Satanic designs: “…the Satan that one encounters in Barry’s work is the hero who embodies the spirit of undaunted revolt” (The Life and Art of James Barry, pp. 152, 154).

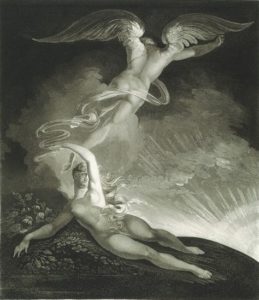

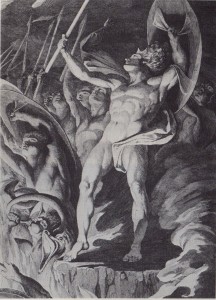

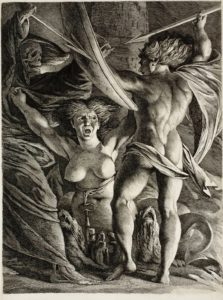

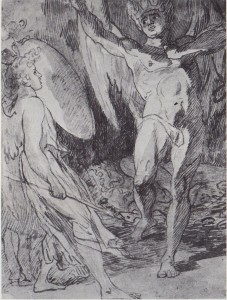

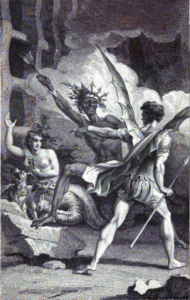

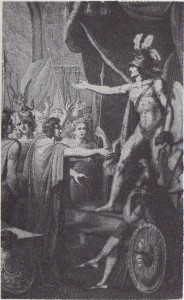

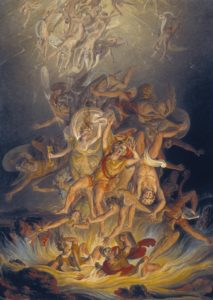

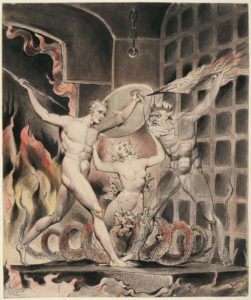

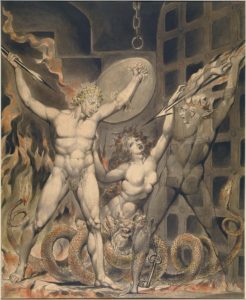

Barry’s Satan, like Fuseli’s, is pictured as a heroic male nude, and Barry has Satan dominate each image to the point of threatening to burst out of the frame, which necessitated the figure of the fallen angel appearing with only a small number of accompanying characters—with one exception: Barry’s grand Satan and His Legions Hurling Defiance toward the Vault of Heaven. This incredible image depicts the scene in Paradise Lost from which its title is derived (I.663–69), but Barry combines this moment with that of the fallen cherub Azazel unfurling the glittering imperial ensign (I.531–43), along with Milton’s powerful description of the preeminent Satan before the rebel hosts he has reassembled from their cataclysmic fall, the ruined yet proudly towering archangel outshining them all by the vestiges of his heavenly radiance (I.589–615)—the moment Burke held up as an expression of the sublime par excellence in his Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. Yet Barry here captures not only Milton’s conception of the awesomeness of Satan’s heroic defiance in Hell, but the intense pathos of his loss as well, as Barry’s Satan gazes upward toward the portion of the sulfurous sky not yet covered by the plumes of infernal smoke, “the lost Arch-Angel” (I.243) about to be permanently severed from the Heaven wherefrom he has been banished. We can likewise discern the “miserable pain” (II.752) of Satan as the Devil’s daughter bursts flaming out of his head in The Birth of Sin, as well as Satan pining the loss of his celestial luster even as he boasts his supremacy to Eden’s angelic guards Ithuriel and Zephon (IV.819–49) in The Detection of Satan by Ithuriel.

Barry’s Satan may be considered Fuselian with his titanic grandeur and heroically handsome features, yet Barry’s Satan is perhaps even more magnificent than Fuseli’s, Barry for instance having exchanged the archangel’s ornate helmet for a diadem as a means of expressing the character’s “Monarchal pride” (II.428). In Paradise Lost, Satan’s shadowy (grand)son Death dons the “likeness of a Kingly Crown” (II.673), but “Barry transfers the crown to Satan,” Pressly notes. “While the poet underscores Death’s ultimate supremacy, the artist is more interested in reinforcing Satan’s majesty” (James Barry: The Artist as Hero, p. 109). The more significant difference, of course, is that Barry’s diademed Devil appears amongst his Heaven-defying troops as a brother-in-arms in Satan and His Legions, whereas in all of Fuseli’s designs the focus is on the majestic Satan so much so that the character becomes rather isolated, which detracts from his noble leadership, as exhibited in Paradise Lost. All in all, Barry’s is a remarkably idealized image, and Pressly asserts that it gives one reason to believe the Roman Catholic Barry was, as Blake said of Milton, “of the Devil’s party without knowing it”: “On one level the artist as a second creator who is attempting to rival God himself runs the risk of provoking the Deity, a most powerful enemy indeed. The greater the artist, the greater the danger that he will be punished for his bold effrontery. Barry never consciously admitted his demiurgic ambition, but in a work such as [this]…, one can sense his deep sympathy for Satan, who stubbornly competes with the Almighty” (James Barry: The Artist as Hero, p. 29). Undeniably, Barry’s illustrations of Milton’s Satan completely reversed what he had achieved in his take on The Fall of Satan (1777), which depicts an armored archangel Michael, gripping a shield and chain in one hand and a thunderbolt in the other, trampling a powerless and faceless Satan underfoot; Barry’s Hell-doomed but Heaven-defiant Miltonic Satan not only equals but far surpasses the artist’s triumphant Michael.

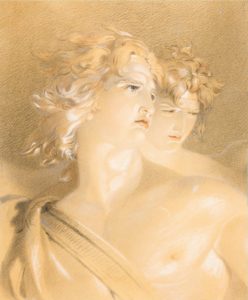

There is admittedly an inconsistency in Barry’s Satanic designs, for while the Satan of his Satan, Sin and Death is similar (though stockier) to that of Satan and His Legions—a wingless fallen angel with a stoic countenance beneath a crowned brow and long, streaming locks of hair—Barry’s bearded rebel angel of Satan at the Abode of Chaos and Old Night appears more aged, and the cherubic-faced figure of The Detection of Satan by Ithuriel and even The Birth of Sin appears more youthful. Incidentally, these are the illustrations in which Barry’s Satan is given wings, which appear angelic.

Barry’s series of Milton designs was a project the artist unfortunately left unfinished on account of several personal setbacks, not least his expulsion from the Royal Academy and the dispiriting completion of Fuseli’s Milton Gallery in the same year. Nevertheless, what Barry managed to produce was a magnificent representation of the Satanic sublime, the artist’s august vision of Milton’s Satan capturing the spirit of Promethean energy and grandeur—and volcanic political insurgence—the Romantic Satanists were drawn to.

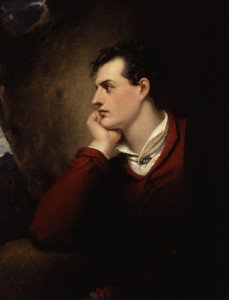

Richard Westall (1765 – 1836)

Westall began his artistic career in 1779 as an apprentice to a silver engraver in London. He started studying at the Royal Academy Schools in 1785, becoming an Associate of the RA in 1792 and full Academician in 1794. Westall would later become the drawing master of the young Princess Victoria, England’s future Queen, and the artist’s only pupil. Westall executed many fine watercolor paintings and portraits—not least one of the most famous portraits of Lord Byron—and even contributed a number of pieces to Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery. Westall was a most accomplished book illustrator, and he contributed a series of illustrations to John and Josiah Boydell’s three-volume edition of Milton, The Poetical Works of John Milton (1794–97). The Satan who emerges from Westall’s vision of Milton’s Paradise Lost is an angelic-winged heroic male nude with a lean, athletic figure and a firm countenance, beneath short, wild curls drooping down over his stoic, tiaraed brow. While William Hazlitt remarked that his figures “look as if cut from wood,” Westall’s Satan exudes tremendous explosive energy a la Fuseli.

Westall’s take on Milton’s Satan is extremely focused on the fallen angel, and this is especially the case with Satan Alarmed—Dilated Stood. Illustrators of Milton typically chose to depict the moment when Satan is discovered by Eden’s patrolling angels Ithuriel and Zephon, the former’s sanctified spear forcing Satan, who had assumed the form of a toad beside the sleeping Eve’s ear, to spring up into his own shape (IV.799–821). Westall chose to illustrate a later moment, when Satan, in the custody of these two, prepares to face off in battle against the archangel Gabriel and his whole angelic squadron, the hellish hero Satan described by Milton “Like Teneriff or Atlas unremov’d: / His stature reacht the Sky, and on his Crest / Sat horror Plum’d…” (IV.987–89). Westall is unique not only for his choice of this later moment, but for choosing to focus solely on the sublime Satan, who, with his towering proud form and dignified visage, appears like a Romantic emblem: the banished rebel—alone against the world—as hero.

Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769 – 1830)

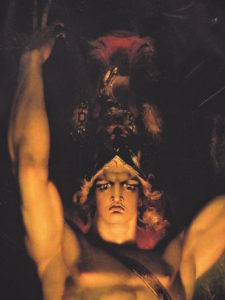

Lawrence was the portraitist of the Regency, producing scores of idealized portraits of English high society, and later commissioned by the Prince Regent (later George IV) to travel across Europe to paint portraits of all of the major figures involved in the downfall of Napoleon (who, incidentally, was seen by both detractors and admirers as the Miltonic Satan made flesh). A true child prodigy, the self-taught Lawrence became an Associate Member of the Royal Academy by 1791, the youngest artist ever elected Royal Academician by 1794, and ultimately the institution’s fourth President in 1820. Lawrence harbored a lifelong love of Milton, reciting passages from Paradise Lost by age five, and the artist felt he accomplished his best work when he set out to portray Satan in all his splendidly ruined, Miltonic magnificence. “It was the endemic element of drama in Lawrence’s nature that was stirred by the fall of Lucifer,” observes English art historian Michael Levey, and there was of course such “glamorous daring implicit in the sinful pride of Lucifer” (Sir Thomas Lawrence, pp. 130, 134). The artist’s monumental take on Milton’s Satan was to be Satan Summoning His Legions, one of a handful of attempts by Lawrence to try his hand at history painting, the result of which is not only epic in subject but in scale: the towering figures of Satan and Beëlzebub dominate the massive canvas (14 feet tall and 9 feet wide), their titanic forms dramatically illuminated by the flames of Hell below. “Colossal, fiendish pride was the mood he aimed at,” notes Levey (Sir Thomas Lawrence 1769–1830, p. 18), and Satan Summoning His Legions achieves nothing if not that; indeed, the intensity of Satan’s expression reminds one of Romantic radical William Hazlitt’s encomium on Milton’s heroically unbowed Satan: “Satan is the most heroic subject that ever was chosen for a poem.…His ambition was the greatest, and his punishment was the greatest; but not so his despair, for his fortitude was as great as his sufferings.…[T]he fierceness of tormenting flames is qualified and made innoxious by the greater fierceness of his pride…” (“On Shakespeare and Milton,” Lectures on the English Poets, 1818).

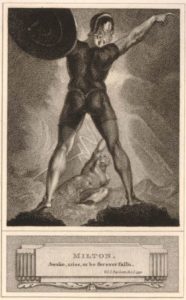

The form of Lawrence’s Satan is based upon that of pugilist John “Gentleman” Jackson (1769–1845), his face that of Shakespearean actor John Philip Kemble (1757–1823). Lawrence’s Satan, with the exception of his ornate helmet and the baldric across his chest, supporting the sword at his hip, is fully nude, his legs astride, his arms—as well as his angelic wings, which are more discernible in the preparatory study—raised in melodramatic flourish. The figure is extremely Fuselian—so much so, in fact, that Fuseli accused Lawrence of copying his vision of Milton’s Satan. (Lawrence would reply by claiming he based his Satan on Fuseli himself—on a pose Lawrence claimed Fuseli struck when overlooking the Bristol Channel, enraptured by its grandness.) Lawrence’s Satan has a youthfully fair countenance and golden bright hair, but the most prominent feature of this princely rebel angel’s flawless face is its piercing eyes, which glare down upon spectators as though they are among Satan’s fallen troops as he commands, “Awake, arise, or be for ever fall’n” (I.330).

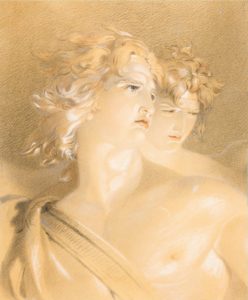

Around the same time Lawrence was working on Satan Summoning His Legions, the artist also executed Satan as the Fallen Angel, a two-thirds profile sketch of Satan with nape-long, windswept hair, the fallen angel staring off into the infernal distance with glistening eyes, his Apollonian countenance reflecting greater valor than his second-in-command, Beëlzebub, who stands behind him. Lawrence had first sketched portraits of Paradise Lost’s characters in 1785, and his sketch of Milton’s Satan, the artist noted, was rendered not with “horror” but “majesty and bearing”; the same, of course, can be said of Satan as the Fallen Angel. Short of the thunder-scarred visage Milton imagines Satan bearing (I.600–01), Lawrence’s most idealized depictions of the Devil fit Milton’s poetic portrait of Satan quite perfectly.

Satan Summoning His Legions was not particularly well received, its reception mixed at best, and the most famous comment about Lawrence’s Satanic historical subject was claimed by the pseudonymous satirist Anthony Pasquin (John Williams, 1761–1818), who dismissed it as “convey[ing] the idea of a mad German sugar-baker dancing in a conflagration of his own treacle.” All the same, throughout his life Lawrence felt Satan Summoning His Legions to be his very best piece of work, and “was convinced that in Satan he had achieved something no other painter of the time could have – not even Reynolds,” observes Levey (Sir Thomas Lawrence, p. 130). With his Milton designs, this reluctant portrait painter (Lawrence once summarized himself as “Genius…infected by Romance, and wasted by Indolence and Languor”) effectively became the Devil’s portraitist, and the artist maintained, “I would rather paint Satan, bursting into tears, when collecting his ruined angels, than Achilles, radiant in his heavenly arms … rushing on devoted Troy!” While Lawrence’s depictions of Milton’s Satan are few, they are arguably the most impressive of all of Romanticism’s Miltonic iconography.

Richard Corbould (1757 – 1831)

Corbould was primarily a portrait and landscape painter, as well as a book illustrator. His contributions to the Royal Academy spanned the years 1777–1811. Corbould provided illustrations to be engraved for a two-volume edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost published by J. Parsons in 1796, which present a significant shift in Romantic representations of Milton’s Satan, not least his being brought down to size. Corbould’s is a rather youthful Satan—a diabolical Adonis, with smooth facial features and short, curling locks. Corbould chose to clothe Satan once again in the classical attire of muscle cuirass and skirt, but he decided against both the angelic-winged and wingless look in favor of a bat-winged fallen angel, and in this he anticipates Doré’s depictions of Milton’s Satan in the mid-nineteenth century. Corbould’s portrayal of a near-nude Satan in his return to Pandemonium is less successful, but it may perhaps be intended to illustrate the character’s gradual descent as he makes his way through Milton’s poem, which again is an anticipation of Doré’s visual interpretation of Paradise Lost.

Edward Dayes (1763–1804)

Dayes was a watercolor painter and printmaker, who studied under the mezzotint engraver William Pether (1738–1821). Starting his studies at the Royal Academy Schools in 1780, by 1786 Dayes began exhibiting at the RA, which he would continue to do until his death (by his own hand) in 1804. While he was principally a painter of landscapes, near the end of the 1790s Dayes began depicting a number of religious subjects, including The Fall of the Rebel Angels, which views the empyrean expulsion through a Miltonic lens. Dayes depicts Satan’s classically outfitted army plummeting down from a celestial void and plunging into a hellish sandpit, the rebel chief holding his clenched fist up toward the Heaven he has been banished from as he falls. A fine detail of Dayes’ Fall of the Rebel Angels is the inclusion of Sin, the daughter born full-grown from Satan’s head, who, as she explains in Milton’s poem, was not only included “in the general fall” (II.773) of the angels, but was given the key to the gates of Hell (II.774–77), which she firmly grips here. Milton’s Sin further explains that she reflected the prelapsarian Lucifer’s “perfect image” (II.764), and Satan and Sin here certainly share a likeness of youthful fairness, with their rosy cheeks and golden locks. The Fall of the Rebel Angels is a unique depiction, and Dayes’ image of a hapless crowd of falling figures very much anticipates Doré’s vision of Milton’s Paradise Lost in the mid-nineteenth century.

Edward Francis Burney (1760 – 1848)

Burney, who belonged to quite the cultural pedigree, began studying at the Royal Academy Schools in 1776, and with encouragement from the institution’s President, Sir Joshua Reynolds, exhibited at the RA between 1780 and 1803. Primarily a book illustrator, in 1799 Burney was commissioned to create a series of illustrations for C. Whittingham’s edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost, published in 1800. While Burney’s heavy-limbed Satan in extreme gestures may seem somewhat comical, Burney’s choice of angelic beauty (the youthfully fair face, long ringlets of hair, and feathery wings) and classical accoutrements (the ornate helmet, muscle cuirass, skirt, ponderous shield, and massive spear) mark these Milton designs as sympathetic portrayals of the fallen angel so familiar to Romanticism.

William Blake (1757 – 1827)

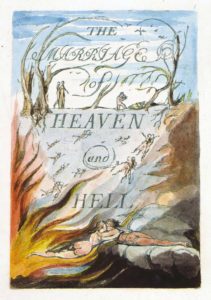

Blake is one of the most iconic figures of Romanticism, though the unique artwork and poetry of this genius went unappreciated—and largely unknown—during his own lifetime. As a youth, Blake’s artistic interests were encouraged by his father, who enrolled Blake in the drawing school of Henry Pars (1734–1806) at the age of ten. Four years later, Blake began an apprenticeship with the engraver James Basire (1730–1802), which lasted seven years. Blake began attending the Royal Academy Schools in 1779 and started exhibiting his own works at the RA the following year, but his involvement with the institution was short-lived. True creativity, Blake felt, was the product of innate genius, which could not—or at least should not—be institutionalized. Blake was crushed by the untimely death of his brother Robert at age 24, but this deep personal crisis also proved inspirational on a creative level, as Blake developed his idiosyncratic method of “relief etching”—or, as Blake called it, “illuminated printing”—which the artist claimed was imparted to him by a vision of his deceased brother. Whereas traditional engraving (intaglio) consisted of etching a design into a copper or steel plate, Blake’s unique etching style would achieve the reverse: a design would be executed on a plate in an acid-resistant medium, the plate then exposed to acid, producing the design in relief, which was then painted, or “illuminated,” by hand. This idiosyncratic method provided Blake with complete creative control over his designs—as well as helped preserve his obscurity—and Blake executed several of his illustrated works this way, not least The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790–93), a cornerstone of Romantic Satanism, and responsible for perhaps the most well-known line about Milton: “Note. The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devils party without knowing it” (pl. 6).

Blake was very much a marginalized figure, for while Blake’s friend and fellow Johnson Circle member Fuseli was seen as eccentric and even borderline mad, Blake was dismissed as a complete madman. (At the very least, Blake was the thin line separating genius from insanity.) Blake was a mystic, claiming to have witnessed visions throughout life, and the Bible—specifically the biblical prophets and their own fantastical visions—remained extremely important to him. A child of Dissenters, Blake would later be drawn for a time to the works of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772), Swedish scientist, theologian, and mystic. Blake even became involved in a local Swedenborgian Church of the New Jerusalem, but ultimately parted ways, largely on account of Swedenborg’s orthodox morality. Blake subscribed to the Romantic view of Jesus as noble rebel, stressing in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell—in part a satire of Swedenborg’s Heaven and Hell (1758)—that Jesus dismissed Jehovah’s laws (see John 8:2–11; Matthew 9:14–17, 12:1–8, 27:11–14), writing, “I tell you, no virtue can exist without breaking these ten commandments: Jesus was all virtue, and acted from impulse: not from rules” (pls. 23–24). In any event, the spiritual realm was always an important part of Blake’s repertoire. A central component of Romanticism was its resistance to the cold rationalism of the Enlightenment, and Blake, who is perhaps the most vivid expression of the Romantic preoccupation with fiery imagination and creativity, felt that religion provided people with much needed spirituality. “Man must & will have Some Religion,” Blake wrote in Jerusalem (1804), and “if he has not the Religion of Jesus, he will have the Religion of Satan…” (pl. 52).

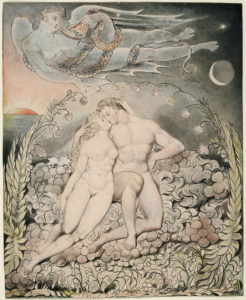

Poets were like the prophets of old, and Blake harbored intense admiration for that “true Poet,” Milton, even claiming to have had a vision of the man in his youth: “…Milton lovd me in childhood & shewd me his face,” Blake wrote to a friend in 1800. So profound was Blake’s fascination with Milton that he wrote an epic poem entitled Milton (1804–10), which Blake considered inspired writing and “the Grandest Poem that this World Contains.” Blake’s “attitude to Milton was always tinged with disapproval for the puritanical, moralistic side of Milton’s work,” notes British art historian Marcia R. Pointon, “but this disapproval was far outweighed by admiration for the creator of Lucifer and for the hedonist who described Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden” (Milton & English Art, p. 136). Indeed, legend has it that Blake and his wife would recite Paradise Lost stark naked in their garden in imitation of Adam and Eve.

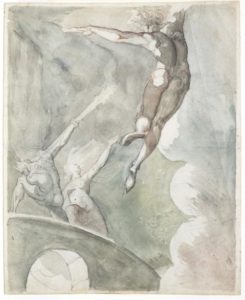

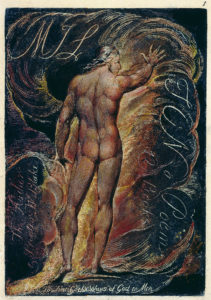

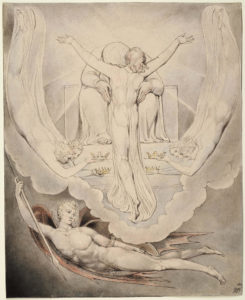

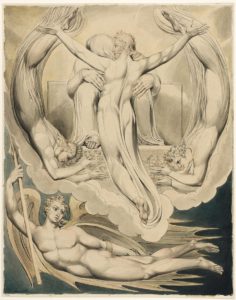

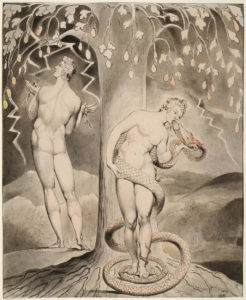

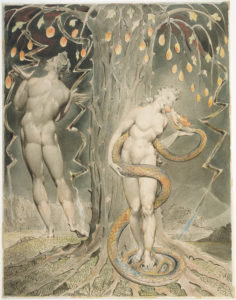

While most of Romanticism’s Miltonic iconography was produced during the 1790s, Blake’s illustrations for Paradise Lost would only arrive late in the first decade of the nineteenth century. There were, however, a number of early attempts, the first of which was Blake’s Satan Approaching the Court of Chaos (ca. 1782–85), which shows the influence of Fuseli, particularly his early Miltonic designs executed in Rome in 1776 (Satan and Death Separated by Sin and Satan Starts from the Touch of Ithuriel’s Spear) and in London around 1781–82 (Satan Departing from the Court of Chaos). Blake would try his hand at illustrating Milton’s Satan again with Satan Exulting over Eve (1795) and Satan calling up his Legions (ca. 1800–05), the second of which begins to approach what would become his vision of Paradise Lost’s underworld, albeit rendered in a far more infernal and gloomy manner. Blake’s Satan in His Original Glory: “Thou Wast Perfect Till Iniquity was Found in Thee” (ca. 1805) marks the iconographical shift in the visionary’s image of Satan. The reference is to Ezekiel 28, traditionally taken as a veiled reference to the fall of the heavenly luminous and bejeweled archangel (cherub in Ezekiel), but it is safe to assume Blake had Milton’s prelapsarian Lucifer in mind when he conceived this regal rebel angel. In 1807, Blake was finally commissioned to create a series of watercolor illustrations for Milton’s Paradise Lost by Rev. Joseph Thomas, and Blake would be commissioned to illustrate Milton twice more: by Thomas Butts in 1808 and by John Linnell in 1822, with the Butts designs emerging as the superior set of the three.

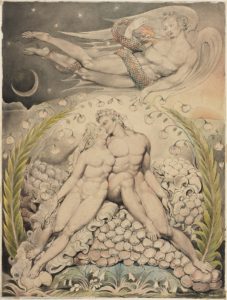

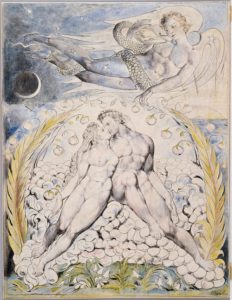

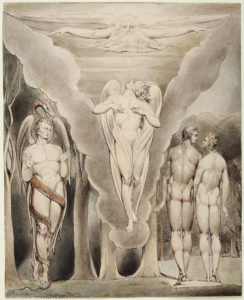

The Satan of Blake’s Paradise Lost designs is reminiscent of the humanized and heroized Satan who appears across Romanticism’s Miltonic iconography, but Blake’s illustrations are nonetheless remarkably unique. “Blake’s drawings were never originally intended for a book,” observe Robert Woof, Howard J. M. Hanley, and Stephen Hebron. “Consequently, he was allowed a freedom in his designs in that he did not have the constraints of the printed page or have to meet the demands of a publisher” (Paradise Lost: The Poem and its Illustrators, p. 23). Blake’s figures, with their taut anatomy, haunting pallor, and dramatic poses, resemble marble sculptures, and with regards to Satan, Blake—more than any other illustrator of Milton—visualizes the character’s tumultuous mélange of defiance and despair, which Paradise Lost emphasizes throughout. Consider for example Blake’s depiction of the winged Satan hovering over the bower of Adam and Eve, deeply pained by the sight of their embrace, and reaching out with longing as he holds in his other hand (as Adam and Eve cradle each other’s heads) the serpent he will later possess to execute the temptation and ruin the innocence of these mortals. This is not a literal representation of the scene, for in Paradise Lost Satan spies on Adam and Eve in the form of a cormorant atop the Tree of Life (IV.194ff.) and first considers the serpent five books later (IX.82–96), but it is the spirit of the scene Blake captures: the fallen angel’s hellish pain and envy of Adam and Eve’s paradisiacal bliss (IV.358–65, 505–11), Satan’s body entangled by the coiling serpent serving as a reminder that the Devil is “to [him]self enthrall’d” (VI.181).

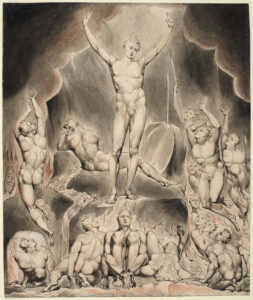

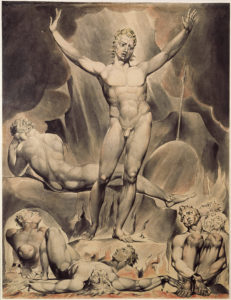

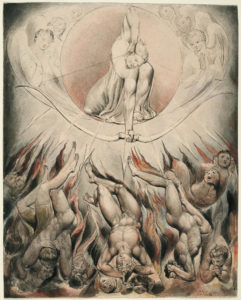

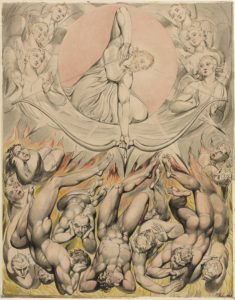

Within his infernal prison, Blake’s Satan is deprived of his wings, but he is surrounded by his fellow fallen angels, whose inclusion is the most important addition to Blake’s designs. Satan summoning his legions was the most favored scene among Romantic artists, and while their Miltonic Satans were undeniably depicted in an astonishingly alluring manner, so focused were they on the Heaven-defiant Devil’s heroic splendor that, with very few exceptions—most significantly Barry’s Satan and His Legions Hurling Defiance toward the Vault of Heaven—Satan’s subordinates went largely overlooked. Romantic iconography’s focus on Milton’s Satan therefore missed an important aspect of the character, which is emphasized throughout Paradise Lost: the deep sense of commitment both Satan and his fallen brethren share. Milton’s Satan is not some petty tyrant whose troops are to him without worth; Satan’s fellow rebel angels are his “Companions dear” (VI.419), and in Hell Satan sheds tears for the “Millions of Spirits” who fell from Heaven “For his revolt,” yet even in damnation stand faithfully before their leader (I.604–20). Milton’s Satan is certainly an imposing figure before his infernal hosts (I.331–38, II.466–75) and speaks openly about why he need not fear rebellion from them (II.21–35), but Satan’s followers do not feel oppressed but rather uplifted by their “great Commander” (I.358): recollecting “his wonted pride,” Satan “gently rais’d / Thir fainting courage, and dispell’d thir fears” (I.527, 529–30). What’s more, when Milton’s soliloquizing Satan engages in a thought experiment on atonement at one point in the poem, one of the reasons he rejects the possibility of repentant submission is his “dread of shame / Among the Spirits beneath…” (IV.82–83). No Romantic artist comes close to Blake in terms of capturing the spirit of this rebellious brotherhood in his vision of Satan summoning his Hell-doomed legions. In fact, the only other illustrator of Milton altogether to achieve this effect would be the French Gustave Doré in the mid-nineteenth century. As Blake would ultimately become one of English Romanticism’s most iconic figures, despite the tragic obscurity and poverty he was subject to in his own lifetime, Blake’s Milton illustrations, in terms of popularity at least, were to become second only to Doré’s.

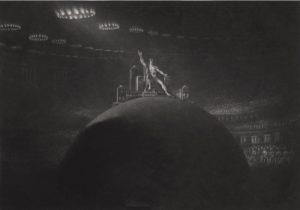

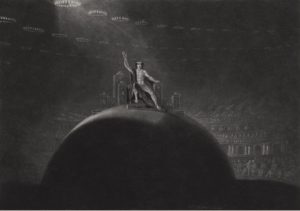

John Martin (1789 – 1854)

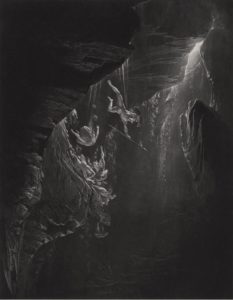

Martin was a painter of sublime landscapes depicting fantastical scenes of cataclysmic destruction, which were tremendously influential on early-twentieth-century epic cinema. So central was the motif of the apocalyptic to Martin’s artwork that when York Minster was set fire to in 1829, the sublime scene conjured up the works of Martin for a woman watching the conflagration. (Ironically enough, unbeknownst to her, the perpetrator was Martin’s older brother Jonathan, who would thereafter be known as “Mad Martin.”) Martin would become a master of mezzotint, the engraving style allowing for extremes of dark and light, working from the former rather than the latter. It was in this style that Martin executed two sets of illustrations for the Septimus Prowett (1797–1867) edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost of 1827. “The greatest literary sublimities were to be found in those parts of Paradise Lost which feature Lucifer as the heroic over-reacher and trace his fall into hell,” observes English cultural historian Barbara C. Morden, and so “with the Paradise Lost engravings Martin was inspired to extend his own brand of sublimity through the mastery of mezzotint” (John Martin: Apocalypse Now!, p. 61).

Martin’s Satan—a heroic male nude equipped with shield, spear, ornate helmet, and crown—is similar to the Romantic representations of Milton’s Satan which came before, but the fallen archangel of Martin’s mezzotints is nevertheless unique. Martin’s Satan is more often than not winged, and (with the angelic exceptions) his membranous wings resemble not so much bat wings as fish fins. Martin’s most successful execution of Milton’s Satan is undeniably Satan’s encounter with Eden’s guardian angels Ithuriel and Zephon: Martin captures aspects of the fallen angel which eluded other Romantic artists, such as Satan’s titanic size—achieved here by way of the minute figures of the sleeping Adam and Eve at the feet of the opposing angels—as well as Satan’s darkened form, which is made more apparent by the radiance of his celestial counterparts. This captures a very significant aspect of the scene, as Satan scorns Ithuriel and Zephon for their failure to recognize Heaven’s former preeminent angelic prince, yet inwardly pines his loss of his erstwhile undiminished brightness (IV.819–49). With the exception of Martin’s take on Satan’s encounter with Sin and Death, the remainder of Martin’s designs render Satan and the accompanying figures in diminutive form, completely dwarfed by the massive environments they inhabit. Later in life, Martin would become involved in creating engineering designs, most significantly for London’s sewer systems, and these ideas appear to have colored the artist’s vision of Paradise Lost’s cavernous underworld. Martin’s Miltonic designs—wherein the rebel angel who sought to scale the heavens and unseat the Almighty Himself is significantly diminished in size in his hellish prison—capture the pathos of this remarkable Romantic era, which celebrated Milton’s Satan and exalted the fallen angel to his pictorial apex, drawing to a close.

Romanticism’s Miltonic iconography presents us with the most idealized imagery of the Devil in the history of Christendom. Curiously, unlike Romanticism’s Satanic poetry and prose, the era’s Satanic artwork was not particularly controversial. A vast majority of the artists included here were Royal Academicians or at least exhibited at the Royal Academy. Why was this art establishment, upon which hung the proud British identity and its grand claims to cultural greatness, permitted to be so sympathetic to Satan?

Of course, there was always the explanation that these Romantic artists of the Satanic were merely portraying what Milton’s poetry so dynamically describes; yet that is not dissimilar to the excuse radical Romantic poets resorted to. Lord Byron, who alongside Percy Bysshe Shelley was infamously demonized as part of a “Satanic School…characterised by a Satanic spirit of pride and audacious impiety” by Poet Laureate Robert Southey in 1821, defended his own Promethean portrayal of Lucifer in Cain: A Mystery (1821) by invoking the precedent of Milton: “I have made Lucifer say no more in his defence than was absolutely necessary,—not half so much as Milton makes his Satan do.” Byron would go on to insist, “If ‘Cain’ be blasphemous, ‘Paradise Lost’ is blasphemous; and the words of the Oxford gentleman, ‘Evil, be thou my good!’ [IV.110] are from that very poem, from the mouth of Satan,—and is there any thing more in that of Lucifer, in the Mystery? ‘Cain’ is nothing more than a drama, not a piece of argument.” These disclaimers—which, it must be said, were rather disingenuous, if strategically so—were ineffectual, and both Byron and Shelley had been driven out of England for their irreverent and irreligious attitudes and conduct, which their detractors believed resulted in their misguided sympathies for the Miltonic Satan. This simply was not the case with Romantic artists, who treated Milton’s Satan no less sympathetically in their historical paintings.

It is also worth noting that while some of the British Romantic artists certainly harbored republican sympathies or were inspired by the outbreak of the French Revolution—and courted suspicion accordingly—this was not the case across the board. Why then did all of these painters and draftsmen delight in depicting the Miltonic arch-rebel in such a heroic light, and why was the pictorial restoration of Lucifer’s luster received without protest within the royally sanctioned British art establishment? The answer appears to lie in the ambiguity of artwork: while the Romantic Satanists clearly emulated the Miltonic mutiny of the angels in their poetry and prose, which channeled the spirit of Milton’s “Apostate Angel” (I.125) and put his celestial revolt to earthly use as a sociopolitical countermyth, the intent of Romanticism’s Miltonic iconography was far more ambiguous. Romantic Satanic artwork may be the simplest means of registering the extent of the fallen angel’s elevation during this revolutionary period, but at the time images of elevated evil could also serve to demonize the luminous ideals of those who dared to dream of shaking up society. John Hutton asserts that “the rebellious image of the heroicized Satan was quickly reduced in the dominant artistic discourse to a mere motif,” and just as Milton’s God “Out of [Satan’s] evil seek[s] to bring forth good” (I.163), those opposed to social change could simply turn the image of the Devil as idealized arch-revolutionary to counterrevolutionary ends:

To the extent, in fact, that the icon of the heroic Satan found an enduring niche in dominant culture, it worked ultimately to reinforce authority. It was asserted that (just as in France) figures and ideas beautiful on the surface were actually forces for evil. …Satan no longer had to be hideous, with hoofs, horns, or a snout. Instead, he served as symbol for the seductive beauty of the sin of pride. In an environment in which the very idea of political (much less social) equality was condemned as a heresy of the first order—albeit one disturbingly attractive to the poor and middle classes—it could be seen as altogether appropriate to focus on the false pride of Satan, who dared to claim for the angels equality with God, and on the seeming beauty of rebellion. (“ ‘Lovers of Wild Rebellion’: The Image of Satan in British Art of the Revolutionary Era,” in Blake, Politics, and History, ed. Jackie DiSalvo, G. A. Rosso, and Christopher Z. Hobson, pp. 162–63)

Milton’s rebellious republicanism notwithstanding, one can argue that something similar is at play in Paradise Lost itself, and indeed the poem’s sublime Satan has been explained away by some Milton critics as the poet’s honest effort to portray a convincing Tempter, whose prideful disobedience excites and attracts even as it destroys. After all, as Milton’s Adam observes, “Subtle he needs must be, who could seduce / Angels” (IX.307–8), and the Bible itself warned of the Devil’s deceptive ability to transform himself “into an angel of light” (2 Corinthians 11:14). Romantic art’s alluring Lucifer could serve to demonstrate visually such Satanic falsity: the Devil’s handsome and heroic features as a mere a façade, a perfect representation of seductive but ultimately destructive resistance to the status quo.

The same effect can be traced in the case of Romanticism’s feminist pioneer Mary Wollstonecraft, whose treatise A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) proposed a rebellious rereading of Milton’s Paradise Lost, within which woman is reimagined as a sublimely Satanic revolutionary of sorts. Christendom had subjugated women on the basis of Eve—who was designed to be Adam’s “help meet” (Genesis 2:18)—succumbing to the Serpent of Eden’s temptation to eat the forbidden fruit of the tree of knowledge, drawing Adam to fall with her into Satan’s seduction to “be as gods” (Genesis 3:5). Just as Lucifer caused the fall of the angels by aspiring above his sphere and pursuing his proud ambition to “be like the most High” (Isaiah 14:14), the Church Fathers held, so too had Eve caused the Fall of Man on account of her failure to know her place. “Let the woman learn in silence with all subjection,” advised St. Paul. “But I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man, but to be in silence. For Adam was first formed, then Eve. And Adam was not deceived, but the woman being deceived was in the transgression” (1 Timothy 2:11–14). Eve was placed under the rule of Adam as punishment for her transgressive act (Genesis 3:16), and her daughters were in turn to inherit this subjection to their husbands. Wollstonecraft turned the Judeo-Christian demonization of women on its head, asserting in her Vindication that “instead of envying the lovely pair [Milton’s Adam and Eve], I have, with conscious dignity, or Satanic pride, turned to hell for sublimer objects,” and throughout the work she aligns defiant woman with Milton’s sublime Satan. Wollstonecraft’s detractors, however, capitalized on this to demonstrate that such resistance to divinely ordained patriarchy was just as perverted as they claimed. (See Steven Blakemore, “Rebellious Reading: The Doubleness of Wollstonecraft’s Subversion of Paradise Lost.”) Wollstonecraftian feminism and the liberal ideals of the French Revolution were on the winning side of history, however, and so placing these under the aegis of the fallen angel so as to demonize them would of course backfire, ultimately serving more to humanize and heroicize Satan, lending credence to the Romantic notion of Lucifer as liberator. The same can be said of Romanticism’s apotheosis of Milton’s Satan in the visual arts: whatever the intentions of the forces of reaction in allowing for this, Lucifer appears to have had last laugh.

If in the case of Romantic art the fallen angel had broken his fetters, this phenomenon was but a mirror image of painting’s sister art, poetry: Milton himself had employed the tactic of elevating the evil angel to Satanize the virtues he signifies in Paradise Lost, but as three and a half centuries of Milton criticism have shown, it is not at all apparent that the poet achieved his desired end by doing so. The grandly luminous Lucifer brought to life in Romanticism’s Miltonic iconography is, it is worth noting once again, the closest artists have ever come to a proper portrayal of Milton’s Satan, which is to say, Milton himself conceded to Satan much of the same magnificence as the turn-of-the-nineteenth-century British art world. “Milton was too magnanimous and open an antagonist to support his argument by the bye-tricks of a hump and cloven foot,” observed the great Romantic critic and essayist William Hazlitt in his Lectures on the English Poets (1818). “He relied on the justice of his cause, and did not scruple to give the devil his due.” Yet the fact of the matter is that Milton had given his Devil far more than his due—or, as Hazlitt put it, “carried his liberality too far, and injured the cause he professed to espouse by making him the chief person in his poem,” for indeed “the interest of the poem arises from the daring ambition and fierce passions of Satan.…The two first books alone are like two massy pillars of solid gold.” Books I and II of Paradise Lost—the infernal books—are so strong and so beautiful because of the heroic Satan who dominates the action therein. Milton’s Satan is a classical commander, his rebel troops likened to heroic Greeks and Romans (I.549–55, 667–69), and “thir mighty Chief” (I.566) calls to mind the greatest heroes of classical epic: Satan resembles Homer’s Achilles in his indomitable pride and insatiable wrath; Homer’s Odysseus in his wiles, silver-tongued rhetoric, penchant for disguises, and temerity as a voyager; and Virgil’s Aeneas in his charismatic leadership and his quest to found a new empire for his exiled compatriots. In fact, Milton’s Satan is more heroic than these heroes of old, as Hazlitt observes with obvious relish: “The Achilles of Homer is not more distinct; the Titans were not more vast; Prometheus chained to his rock was not a more terrific example of suffering and of crime.”

The point about Satan’s transgressive Prometheanism is important, for Milton’s Satan is not only a supreme representation of conquest but culture. The Satan of Paradise Lost is Promethean not only in his noble defiance of divine tyranny and his heroic endurance of eternal agony, but for his classical humanism as well. In the ancient Greek tragedian Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound, “every art of mankind comes from Prometheus” (505), but in the Miltonic cosmology they come from Hell: Paradise Lost’s fallen angels, in a scene unfortunately never undertaken by any illustrator of Milton, engage in Olympian games, mining, music, philosophy, and exploration (II.528–628)—all activities worthy of the catalogue of gifts the rock-bound Prometheus of Aeschylus boasts he has bestowed upon the erstwhile unenlightened human race (442–505). Satan is to Milton “Rebel to all Law” (X.83), yet the poet presents this cosmic criminal as the fountainhead of culture, which again is reflected in his own radiant beauty, described magnificently by Hazlitt: “Wherever the figure of Satan is introduced…it is illustrated with the most striking and appropriate images: so that we see it always before us, gigantic, irregular, portentous, uneasy, and disturbed—but dazzling in its faded splendour, the clouded ruins of a god.”

Throughout Paradise Lost, Milton goes well out of his way to render his “Hell-doom’d” (II.697) hero Satan a ruined god, heaping abundant majesty upon the exiled arch-rebel. For example, the industrious fallen angels erect a splendiferous palace that Milton, demonizing the classical pantheon, calls “Pandæmonium, the high Capitol / Of Satan and his Peers” (I.756–57). This “City and proud seat / Of Lucifer” (X.424–25), however, is described by Milton as a marvelous sight far outshining all sublime structures throughout human history (I.710–30), within which Satan is seated atop an incomparably splendid throne (II.1–10). It has been argued by the late literary scholar Roland Mushat Frye that this is yet one more example of Milton, in marked contrast to the medieval mockeries of the Devil as a bestial monster, paradoxically exalting the fallen angel to debase him:

If that throne outshines everything on earth, it outshines far more all that can be found in the traditional infernos of art.…As a general rule, the artists used a visually debased throne as yet another means for ridiculing Satan, whereas Milton employed a gorgeous throne so as to expose Satan by exalting him. Milton heightens, enhances, and dignifies both his demons and their Hell, allowing them to glorify themselves according to their own image; but at the same time, by a beautifully sustained irony, he manages to unmask them through the uninhibited pretentiousness of their attempts at self-elevation. (Milton’s Imagery and the Visual Arts: Iconographic Tradition in the Epic Poems, p. 138)

The Puritan poet Milton and his “fit audience…though few” (VII.31) may remain unimpressed by Satanic splendor, yet to provide his Hell-doomed Devil with such awe-inspiring eminence—despite Milton insisting it is a “bad eminence” (II.6)—was to place his Christian epic poem in an extremely precarious position. To render Satan unsurpassably sublime so as to not only depict a convincing Tempter but to demonize or at least eclipse classical heroism, which to Milton paled in comparison to “the better fortitude / Of Patience and Heroic Martyrdom” (IX.31–32) that constitutes Christian virtue, was to play with truly hellish fire.

It has been observed that Milton’s Satan is descended from a long line of Renaissance Devils (see Stella Purce Revard, The War in Heaven: Paradise Lost and the Tradition of Satan’s Rebellion), all of which were catalogued by Watson Kirkconnell in his 1952 tome The Celestial Cycle. While these Renaissance works may anticipate Milton’s Paradise Lost, most significantly by conceding to their Satans a certain degree of proto-Miltonic majesty—the most striking example of which is the Dutch playwright Joost van den Vondel’s Lucifer (1654)—Paradise Lost’s Prince of Darkness outshines all of them. For instance, however generous Milton’s Renaissance predecessors might have been when depicting Lucifer’s heavenly revolt, they were unquestionably far more unforgiving when visualizing his infernal fall, as they all uphold the medieval tradition of defacing the fallen angels by transforming them into malformed monstrosities. In Paradise Lost, Satan the heavenly rebel angel is described as “Sun-bright” (VI.100), and yet Satan the hellish fallen angel—the so-called “Prince of Darkness” (X.383)—is still likened to the Sun, though as obscured by a misty horizon or eclipsed by the Moon (I.592–99). In short, Milton’s Satan remains in possession of a considerable degree of his “Original brightness” (I.592), as does the fallen “Satanic Host” (VI.392), which Milton likens to a lightning-scorched but nonetheless stately forest (I.612–15). The fallen rebel angels, despite their diminished glory, bear “Godlike shapes and forms / Excelling human, Princely Dignities” (I.358–59), and no one is as princely and godlike as Satan himself, who “above the rest / In shape and gesture proudly eminent / Stood like a Tow’r” (I.589–91), his preeminence signified by his surprising resplendence: “Dark’n’d so, yet shone / Above them all th’ Arch-Angel…” (I.599–600). The only trace of genuine deformity in Milton’s Satan is that “his face / Deep scars of Thunder had intrencht” (I.600–01), and yet the effect produced by these battle scars is not unlike that of Satan’s massive shield’s resemblance to the spotty Moon (I.284–91) or his own resemblance to “a weather-beaten Vessel” with “Shrouds and Tackle torn” (II.1043–44) as he boldly ventures through Chaos on “indefatigable wings” (II.408); Satan’s thunder-scarred visage serves to make him seem more heroic, merely magnifying the impressiveness of his “Brows / Of dauntless courage, and considerate Pride…” (I.602–3).

Of course, at the end of Satan’s journey in Paradise Lost, he and his coconspirators are ultimately brought horrifyingly low by Milton: upon returning to Pandæmonium to inform his compatriots of his earthly triumph, Satan finds himself transformed into “A monstrous Serpent on his Belly prone” (X.514) at the conclusion of his exultant speech, Satan’s supporters suffering the same ignominy, “all transform’d / Alike, to Serpents all as accessories / To his bold Riot…” (X.519–21). Satan’s final scene was certainly overlooked by Romantic artists—and in fact by all but one Miltonic illustrator, Gustave Doré—and William Wordsworth, who presided over the initiation of English Romanticism, even bemoaned this denouement in his annotations to Paradise Lost (ca. 1798): “Here we bid farewell to the first character perhaps ever exhibited in Poetry. And it is not a little to be lamented that, he leaves us in a situation so degraded in comparison with the grandeur of his introduction.” Truth be told, this divine judgment of the devils is not nearly as demeaning as it might have been, for Milton emphasizes that theirs is merely a temporary punishment, an “annual humbling certain number’d days, / To dash thir pride, and joy for Man seduc’t” (X.576–77), and this ignominious metamorphosis concludes with Milton restoring his writhing rebel angels: “…thir lost shape, permitted, they resum’d…” (X.574). What’s most striking about Satan’s degradation scene is not so much that it occurs as that it ends—and is ended so swiftly, as though disciplining his Devil thus were perfunctory for Milton.

If we are to look beyond the poem, however, an honest assessment of the overall effect Milton’s Christian epic has had on the figure of the fallen angel makes it difficult to deny that in Paradise Lost the Pyrrhic victory belongs not to Milton’s Satan but to Milton’s God—and to Milton himself. In the poem, Satan is released from his infernal fetters by the Almighty, who “Left him at large to his own dark designs, / That with reiterated crimes he might / Heap on himself damnation” (I.213–15), as well as reap greater glory for the Godhead, as Satan’s “spite still serves / His glory to augment” (II.385–86). Milton appears to have enjoyed a similar relationship with his poetic creature: the Puritan poet released his Satan upon the world to achieve his own ends—to “justify the ways of God to men” (I.26)—but, like a true Frankenstein monster, Satan appears to have escaped the will of his creator. While “maistring Heav’n’s Supreme” (IX.125) is an impossibility for Satan within the narrative, Milton’s Satan does appear to have been successful in mastering his true creator, Milton. “The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell,” Blake famously theorized in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790–93), “is because he was a true Poet and of the Devils party without knowing it” (pl. 6). Paradise Lost’s sublime Satan essentially sprang forth uncontrollably from Milton’s mind, just as Sin burst unbidden out of Satan’s head (II.749–58), and Milton likewise “Becam’st enamor’d” (II.765) with the creature of his imagination. This Romantic reading of Milton’s poem does not appear to be a misguided assessment or a mischievous misinterpretation; no, it appears rather to be just as accurate as Romantic art’s visualizations of the Satanic sublime.

“Satan is the most heroic subject that ever was chosen for a poem,” Hazlitt pronounced in his aforementioned Lectures, “and the execution is as perfect as the design is lofty.” The very same can be said of the Miltonic iconography of Romanticism, whose artists of the Satanic were definitely of the Devil’s party, whether or not they knew it. Romanticism’s “reimagined figure of Milton’s Satan embodied for the age the apotheosis of human desire and power,” explains Peter A. Schock in the sole book-length study of the Romantic Satanism phenomenon, and so “Milton’s Satan assumes in the Romantic era a prominence seen never before or since…” (Romantic Satanism: Myth and the Historical Moment in Blake, Shelley, and Byron, p. 3). Nowhere is this more apparent than in Romanticism’s Miltonic iconography, which served to make prophetic Satan’s declaration from the depths of Hell in Paradise Lost: that he, “rising, will appear / More glorious and more dread than from no fall…” (II.15–16).