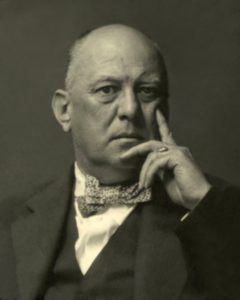

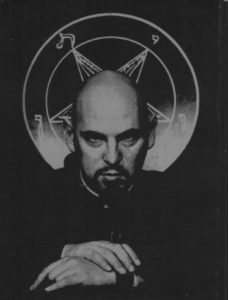

Church of Satan founder Anton LaVey established within the Satanism he codified an aesthetic of goatish ghoulishness, as opposed to the Miltonic majesty associated with Romanticism’s Satanic iconography. Many Satanic organizations competing with LaVey’s have come and gone over the years, and yet somehow exploiting the magnificent imagery of Satan produced by the Miltonic-Romantic tradition has not proven to be the interest of any of them. Modern, organized Satanism would seem stuck in the aesthetic set by LaVeyan Satanism and, ironically enough, dictated by popular culture.

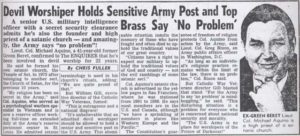

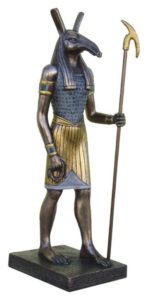

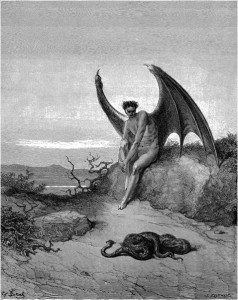

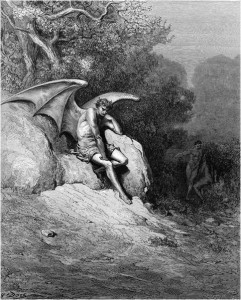

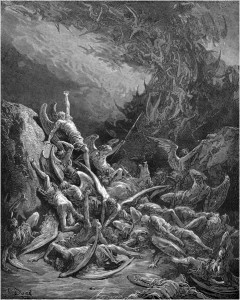

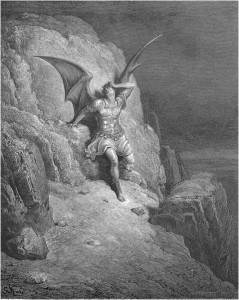

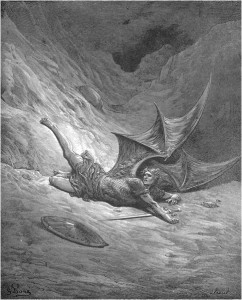

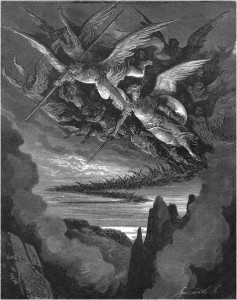

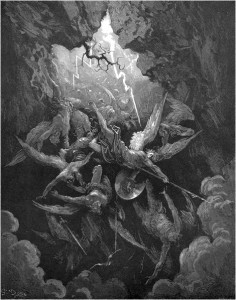

LaVeyan Satanism’s first significant breakaway organization came in 1975 in the form of The Temple of Set, established by “the Black Pope” LaVey’s onetime trusted lieutenant, Michael A. Aquino. According to Aquino, LaVey’s carnivalesque presentation of Satanic philosophy and lifestyle was a major contributing factor in his dramatic departure from the Church of Satan. For example, Aquino relates in his mammoth, two-volume Church of Satan tome that one of his clashes with LaVey was over the cover image of the organization’s official bulletin, The Cloven Hoof: Aquino, the publication’s editor, preferred “a bat-winged, Miltonian Satan hurling bolts of fire across the page to form the blazing words ‘Cloven Hoof,’ ” but LaVey decided upon “a magnificently hideous Baphomet goat-dæmon, whose most inescapable feature was a hairy, erect phallus.”1 It is an amusing anecdote, but despite Aquino’s preferred iconography of a “Miltonian Satan” (Gustave Doré illustrations for Paradise Lost adorn both volumes of Aquino’s Church of Satan)—as well as his Romantic reading of Paradise Lost as “one of the most exalted statements of Satanism ever written”2 and his assertion that its “Miltonian Lucifer is, in fact, our Satanic man”3—Aquino was not above defending the Church of Satan’s goatish aesthetic,4 and, more importantly, when he parted ways with LaVey and took a number of disgruntled Church of Satan members with him in the summer of ’75, what Aquino opted for was not Miltonian but Egyptian. Founding a Temple of Set, Aquino would exchange Satan for Set, the local-chapter “grottoes” for “pylons,” and street-smart selfishness for Xeper (“becoming”).

The Miltonic-Romantic tradition’s significance to modern Satanism does not look promising if it was overlooked by the most Miltonic-minded high-profile Satanist. Indeed, the various rival Satanic organizations over the span of the half-century organized Satanism has enjoyed either closely mimicked LaVey’s synthesis of Satanic aesthetics (as well as ideology) or followed Aquino’s lead and opted for a style so disassociated from the Western conception of the Devil that they would never gain the prominence of a church “consecrated” in the name of the infernal figure the West is most familiar with.

New Satanic Organization, Same Old Goatish Satan

Today, the Church of Satan’s most significant competition has come in the form of The Satanic Temple, which has gained increasing infamy since its 2012 inception on account of its members’ sociopolitical engagement, which the Church of Satan has always refrained from. LaVey imagined Satanism as an extremely personal endeavor—not a cause demanding contributions but a system for living life to the fullest for radical individualists with macabre sensibilities. While LaVey was a firm believer in the separation of church and state, he did not feel it was appropriate for his organization to take any official political positions; rather, Satanists should work out on an individual basis which political positions and parties best suit their self-interests. The Satanic Temple, by contrast, is overtly political, its Satanic philosophy intertwined with progressive politics, and its members encouraged to engage in political activism to actualize its vision of a more secular society. “No tolerance for religious beliefs secularized and incorporated into law and order issues,” insisted LaVey in his “Pentagonal Revisionism: A Five-Point Program,”5 but The Satanic Temple feels simply stating a belief in secularism is insufficient; self-declared Satanists should instead dedicate their energies to transforming society along these lines. The Satanic Temple endeavors to accomplish this by engaging in high-profile activism—summarily dismissed by the Church of Satan as the embarrassing political stunts of “Satanic Social Justice Warriors”—intended to combat religious encroachment upon what was intended to be, or at least what should be, a secular society, principally by drawing attention to breaches of the wall separating church and state. Many of these battles focused on the placement of religious icons on state grounds or in public spaces, The Satanic Temple chooses to enter the fray by demanding equal representation and, as a result, poisons the well, so to speak, as these battles tend to end in religionists withdrawing altogether from promoting their beliefs in the public sphere if it means sharing the same space with Satan. This, The Satanic Temple’s members refer to as “Lucien’s Law,” after Lucien Greaves, cofounder of the organization.6

But what concerns us here is aesthetics. The Satanic Temple, like the Church of Satan, claims to follow in the Miltonic-Romantic tradition. “Ours is the literary Satan best exemplified by Milton and the Romantic Satanists,” the organization’s website explicitly states, yet, again like the Church of Satan, it offers up very little in terms of visual links to that Miltonic-Romantic tradition. In fact, while members of The Satanic Temple may be eager to distinguish its philosophy from that of LaVeyan Satanism—specifically the latter’s coldhearted Social Darwinism—its imagery is practically indistinguishable from the Church of Satan’s. The Satanic Temple offers up more goats, more horns, more skulls, and more Halloween-style imagery in general. (Like the campy Coop Devil embraced by the Church of Satan, The Satanic Temple also offers a more satirical Satan in the form of the mascot for its “After School Satan” clubs, but such deliberately tongue-in-cheek icons are exceptions; the symbolism of both Satanic organizations is predominantly dark and sinister, intended to shock and scare the strait-laced.)

These younger Satanists of The Satanic Temple maintain that such iconography is inherently Satanic with or without the legacy of LaVey, and thus could be used at liberty, as the Church of Satan cannot claim a copyright on it. That’s fair enough, but could does not necessarily mean should, and it does appear to be the case that The Satanic Temple’s exploitation of the gloomy aesthetic it shares with the Church of Satan clashes with the far different message it wishes to put out. Frightful feral imagery is not incongruent with the cold, often brutal devil-take-the-hindmost philosophy endorsed by LaVeyan Satanism7 and its celebration of a bestial Satan that “represents man as just another animal,”8 whereas The Satanic Temple’s use of the same imagery seems counterintuitive to its stress on a less animalistic and more humanitarian strain of Satanism, what with its tenets such as “strive to act with compassion and empathy towards all creatures,” the “struggle for justice is an ongoing and necessary pursuit,” and “the freedoms of others should be respected…” Is it not jarring for tenets such as these to be set against a pitch-black background and flanked by goat-headed skeletons? Such a Halloween-every-day ethos is surely harmless and good fun—as attested to by the great popularity of shows like The Addams Family and The Munsters, or Halloween itself having increasingly grown from a peculiar autumn holiday to a year-round lifestyle for many otherwise conventional people—but for an organization that claims such respectable literary, artistic, and cultural roots, and that claims to be channeling this profound energy into real-world political action, the harmless horror sensibility seems rather out of place.

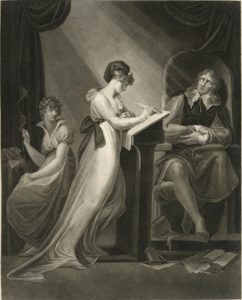

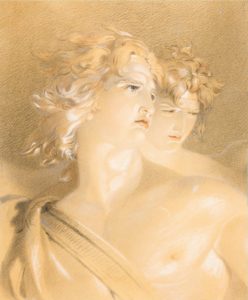

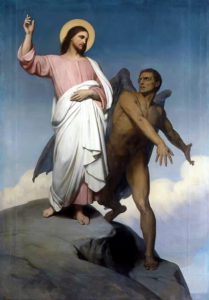

Romantic Satanism, despite its tragic and melancholic elements, was fundamentally humanistic, its titanic Lucifer an emblem of humanity’s lofty drive for transcendence, which differentiates us from our fellow beasts of the field (or so at least the Romantics believed9). This sentiment was expressed in the Romantic Satan’s appearance, which was within the era’s Miltonic iconography wholly humanized and heroicized—the arch-rebel as “an image of apotheosis,” in the words of Peter A. Schock, “an emblem of an aspiring, rebelling, rising human god who insists that he is self-created.”10 “Though we could take from the imagery of those such as William Blake or Gustave Doré exemplifying the beauty of purity of the fallen angel,” Satanic Temple spokesperson Stu de Haan explained to me,

we prefer to use the more well-known and arbitrarily offensive imagery exemplified by the media and pop culture…Fully aware of the trite offense these images may provoke, this is a statement that our “freedom to offend” is in the nature of our very existence; an existence that strives to demonstrate that the heckler’s veto has no bearing on our beliefs or our rights.

This preference for more offensive imagery playing upon pop cultural stereotypes is most apparent in the icon that crystallized The Satanic Temple’s goatish aesthetic: a nine-foot, two-ton monument of Baphomet, which the organization sought to situate outside of the Oklahoma State Capitol in contrast to its Ten Commandments monument—a campaign which, in accordance with Lucien’s Law, was terminated upon the Supreme Court of Oklahoma’s decision to remove the Ten Commandments. (At time of writing, The Satanic Temple is planning to relocate its Baphomet monument to the Arkansas State Capitol, where the Devil is once again intended to contrast the Decalogue.)

The Satanic Temple’s monumental Baphomet is fairly close to the Éliphas Lévi “Sabbatic Goat” design, save for the removal of the female breasts (a move made so as to evade being barred on account of accusations of obscenity) and the humanoid goat figure being flanked not by waning and waxing moons but by two children—a Caucasian girl and an African-American boy, which, while apparently an incidental choice on the part of the artist, would seem to evoke progressive politics’ hobbyhorses of sexism and racism. Also, it was at least at one point planned for the back of the Baphomet monument to be inscribed with the following Luciferian lines from Lord Byron’s Cain (1821):

Then who was the demon? He

Who would not let ye live, or he who would

Have made ye live for ever in the joy

And power of knowledge? (I.i.207–10)

It is a quintessentially Romantic sentiment—and a commendable connection to Romantic Satanism—but it is difficult indeed to imagine such magnificent verse being put in the mouth of the beastly Baphomet. As with the Church of Satan, there is an obvious aesthetic disconnect between the Miltonic-Romantic heritage that The Satanic Temple ostensibly lays claim to and the goatish gloom with which it promotes itself. While there are undeniably many who will never understand Satanism regardless of how carefully and thoroughly the concept may be explained to them, Satanists perhaps can’t complain too much if their message of Satan-as-hero fails to register with people who are presented with imagery which, contrary to Romanticism’s Miltonic iconography, fails to connote that idea.

I discussed the matter of Satanic aesthetics with the Church of Satan’s self-styled “Irreverend” Gavin Baddeley, who observed, “Satanism has this ghoulish, abrasive, quite cartoonish imagery which has very little overlap with the Romantic/Miltonic ideal…I think that aspect of it has been underplayed…[but] I think it’s a difficult sell, to a certain extent, because when people want Satanism they want…explosions and goats.” Baddeley went on to explain that presenting Satanism to the media is especially tricky because there is a preconceived notion of what Satanism looks like—based upon popular culture in general and horror movies in particular—which a presenter of Satanism must, at least to a degree, placate. “If I suggested we get out some Greco-Roman statues, they wouldn’t buy it.…[If] you deal with the media and you try and present them something which isn’t what they’ve already decided they want, then you’ve got an uphill struggle that usually leads nowhere.” Baddeley would know best, as he is the foremost authority on Satanism in the UK, but this is a rather striking issue, if it is the case: Satanism is meant to be a radically individualistic creed that breaks away from Western culture’s Judeo-Christian confines and is adversarial to conformity broadly speaking, yet for Satanism to survive Satanists must exploit imagery which has been largely crafted and instilled in the popular consciousness by the Christian Church and mass media. Ultimately, then, Satanism in relation to society is not so much autonomous as symbiotic. Baddeley suggested that before Satanism could truly make use of Romanticism’s rich Miltonic iconography or any kind of imagery inspired by it, an aesthetical evolution within Satanism that places greater emphasis on its literary and cultural roots would have to take place first. That may be so, but such an evolution occurring any time soon—if at all—appears dubious. Indeed, The Satanic Temple’s headquarters in Salem, Massachusetts doubles as an art gallery, and among its many pieces is Baphomet in baby form, which apparently is meant to symbolize the Satanic rebirth the organization feels its members are at the forefront of. Baby Baphomet would seem to imply, however, that this supposed Satanic renaissance is simply to recycle the same old goatish and ghoulish aesthetic of the Satanism of yore.

It is curious indeed that The Satanic Temple, in its efforts to distinguish itself from LaVey and the Church of Satan, has not endeavored more to evolve Satanism in terms of imagery and aesthetics. Mark Porter, the artist employed by The Satanic Temple to construct the massive Baphomet monument, was trained in classical sculpture, and one imagines Porter would have warmed to the opportunity to create a Satan in the spirit of Romantic interpretations of the fallen archangel, the dynamic figure rendered as a handsome classical hero, as per Milton’s Paradise Lost. In addition to the many examples provided by Romantic history painting, there are also sculptural precedents of such a Satan, such as Joseph Geefs’ L’ange du Mal (The Angel of Evil, 1842), Guillaume Geefs’ Le Génie du Mal (The Genius of Evil, 1848), Costantino Corti’s Lucifero (1867), and last but certainly not least, Ricardo Bellver’s El Ángel Caído (The Fallen Angel, 1877). These nineteenth-century Satanic sculptures, which were clearly inspired by the Miltonic-Romantic tradition (Bellver’s is based upon Milton’s first description of the Hell-doomed Devil in Paradise Lost), imagine Satan more as Grecian god than goat, and the result is magnificent, whether the fallen angel sports the wings of an angel or of a bat. Modern Satanism falls far short of such Miltonic majesty. While The Satanic Temple holds that its aesthetic sense is not static and has the potential to evolve, it is difficult to imagine the organization being able to move beyond the gloomy goatish imagery it has promoted up to the present moment in its generous press coverage. (In late 2015, CNN dedicated an hour-long documentary to The Satanic Temple and the unveiling of its Baphomet monument, which is the most mainstream and unbiased attention organized Satanism has ever received since The History Channel’s five-minute coverage of the Church of Satan in its two-hour program on Hell and the Devil about a decade prior.)

The Return of the Miltonic-Romantic Rebel Angel

Whatever we might think of the prospect of public Satanic monuments—likely a misguided idea with a great deal of unintended consequences, in this writer’s opinion—are we really to believe a statue of Satan less goatish and more godlike would be less worthwhile? If anything, such a display may possibly generate greater controversy and garner more attention, as it would surely draw censure for depicting the Devil in a human and heroic light, largely unexposed as the general public is to the Miltonic-Romantic tradition’s reinterpretation of the fallen angel. Is Romanticism’s Miltonic imagery less relevant now than it was around the turn of the nineteenth century? The opposite appears to be the case. People are as drawn to myths of the superhuman as ever, whether it’s Greco-Roman demigods or Marvel and DC superheroes on the silver screen. (The present popularity of the Norse demigod Thor—or, more appropriately, his diabolical foe Loki—highlights the blurring of these categories.) We are undoubtedly living in the age of the superhero, as attested to by the ongoing tsunami of comic-book films, made with monstrous budgets and megastars in the lead roles, and raking in absurd amounts of money as they not only incite an almost religious investment among the fan base but manage to maintain the continued interest of filmgoers at large; in this cultural context the Romantic iconography of a superhuman Satan would seem more appropriate than ever.

Many have recognized a comic book element to Milton’s Paradise Lost. “Readers have always thrilled to Milton’s heroic superheroes and indestructible arch-villains,” writes Edward M. Cifelli in his Introduction to a 2000 Signet Classics edition of Paradise Lost, explaining that Milton’s are “characters who may remind younger readers of comic books, movies, television shows, and computer games.”11 Renditions of these Miltonic characters in the visual arts have drawn similar commentary. Take, for example, the work of the Swiss-born Romantic painter and draftsman Henry Fuseli, the most prolific illustrator of the Miltonic Satan, which earned him the unofficial moniker “Painter in Ordinary to the Devil.” Milton’s Satan lent himself to Fuseli’s extraordinarily distinct art style, fitting in perfectly with the artist’s gigantically imagined heroes with elongated limbs and exaggerated musculature, depicted in violent and gravity-defiant melodramatic poses. In the 2006 Tate Britain exhibition entitled “Gothic Nightmares: Fuseli, Blake and the Romantic Imagination” (Feb. 15 – May 1, 2006), the Satanic artwork of Fuseli, as well as that of Blake and Barry, was tellingly included in the “Superheroes” room of the exhibit/chapter of the exhibition catalogue.12 Martin Myrone, curator of the “Gothic Nightmares” exhibition and Tate Britain’s lead curator of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century British art, notes that Fuseli’s “vividly stylised images of ghosts and fairies, muscle-bound superheroes, fainting maidens and voracious viragos are obvious prototypes for the figures in today’s comic-books, action movies and computer games.”13 Myrone reinforces his point with a reference to Fuseli’s Satan Starts from the Touch of Ithuriel’s Spear (1776), one of the artist’s Roman sketches which he would later flesh out into a full-fledged painting (1779) that would be exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1780 and later featured in Fuseli’s own Milton Gallery (1799, 1800), which was abundant with similar sublime canvases depicting Paradise Lost’s superhumanly heroic and handsome Satan.

While Fuseli’s Milton Gallery, despite the artist’s monomaniacal commitment to the project over the span of a decade (1790–1800), may have been a dismal failure commercially, Fuseli would find his audience two centuries later, as an exhibition held in Stuttgart, Germany gathering together a great many of the Miltonic works executed throughout Fuseli’s astounding career drew some 20,000 attendees from around the world. Miltonists Wendy Furman-Adams and Virginia James Tufte, who attended the “Johann Heinrich Füssli: Das Verlorene Paradies” exhibition (Sep. 27, 1997 – Jan. 11, 1998), explain in “The Choreography of Passion: Henry Fuseli’s Milton Gallery, 1799/1998” that “in an already weak market, the Milton Gallery paintings simply failed to sell. Blake, however, was among the Gallery’s handful of defenders and prophesied that ‘two centuries’ of ‘advance in civilization’ would bring the world to a fitting appreciation of his friend’s sublime achievement. Those two centuries, indeed, brought the Milton Gallery to Stuttgart.”14 Two decades have passed since Satan stole the show at the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, and today’s comic-book culture seems uniquely prepared to receive such a Fuselian fallen angel—a Satan more Michelangelesque than grotesque. It should come as no surprise that the most significant modern-day manifestation of such a Satan derived from the Miltonic-Romantic tradition’s archangelic arch-rebel has come in the form of a comic book, Vertigo’s Lucifer (1999–2006; 2015–2017). Likewise, the Paradise Lost film, before its plug was pulled and the project was consigned to development hell indefinitely, was unsurprisingly being promoted at the San Diego Comic-Con. (Admittedly, the defunct film’s concept art for the infernal regions—which is more in the spirit of a Silent Hill videogame than the poetry of Paradise Lost—indicated that the filmmakers were likely to gravitate toward popular Satanic stereotypes much more than Milton’s majestic vision.)

The time seems right for the masses to be exposed to a less bestial and a more sublime, superhuman Satan—a true Satanic renaissance that would surely incite great intrigue. In terms of such elevated imagery, organized Satanism—whether in the form of LaVey’s Church of Satan, Aquino’s Temple of Set, Greaves and company’s Satanic Temple, or any other nominally infernal entity yet to come—is quite simply missing the mark. Given its goat-obsessed aesthetic, modern Satanism frankly appears unlikely to ever be a force for such a glorified Satan, as strange as that may seem. Far more worthwhile than anything the occult has to offer on the subject of Satan is the eighteenth-century cult of Milton and its influence on modern-day treatments of the legend of Lucifer. Just as the literary, artistic, cultural tradition of Romantic Satanism has heaped far more magnificence upon the Devil than the proceedings of organized diabolism, today’s eruptions of neo-Romantic Satanism within the arts are proving to be far more significant in terms of perpetuating the Prince of Darkness derived from the rich Miltonic-Romantic tradition. As with Milton and the Romantics, it would appear belonging to the Devil’s party is far more important than knowing it.

Notes

I recently had the pleasure of sitting down with my old friend Adam and his partner Greg of Nerds with Words, a fun podcast that welcomes diverse individuals for free-flowing conversation that always ventures down the rabbit hole. We engaged in an in-depth discussion of The Satanic Scholar, exploring the origins of the site and its aims of preserving the Miltonic-Romantic legacy of Lucifer and drawing attention to signs of this radical tradition’s echoes and influences today. Along the way were various tangents, a number of non sequiturs, and lots of laughs. You can download the episode on

I recently had the pleasure of sitting down with my old friend Adam and his partner Greg of Nerds with Words, a fun podcast that welcomes diverse individuals for free-flowing conversation that always ventures down the rabbit hole. We engaged in an in-depth discussion of The Satanic Scholar, exploring the origins of the site and its aims of preserving the Miltonic-Romantic legacy of Lucifer and drawing attention to signs of this radical tradition’s echoes and influences today. Along the way were various tangents, a number of non sequiturs, and lots of laughs. You can download the episode on