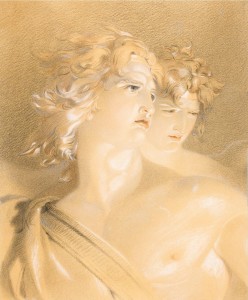

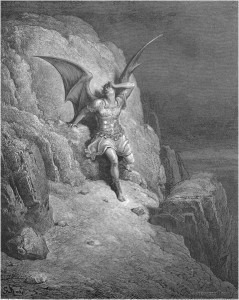

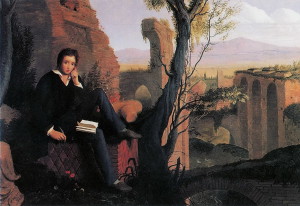

Lucifer on Fox is a loose television adaptation of the Vertigo comic of the same name, Mike Carey’s spinoff series from Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman. While the show shares certain similarities with the Lucifer comic, it is also distinguished by significant differences. As I’ve written extensively about, Carey’s Lucifer is the Miltonic-Romantic Satan’s true heir, but how will the TV incarnation of this character measure up? Let’s explore the possibilities by dissecting the main characters introduced in the Pilot episode, starting with the star of the show—the Morningstar, Lucifer.

Lucifer Morningstar

“I’m like walking heroin—very habit-forming, it never ends well.”

I will reserve extensive analysis of Tom Ellis’ Lucifer for another blog, limiting my commentary here to his character’s general arc in the Pilot. Episode 1 of Lucifer establishes that the fallen angel, bored as the Lord of Hell, which he has ruled over since God—his Father—cast him out from Heaven, decided to take a vacation to Los Angeles. Lucifer, the owner of Lux—here upgraded (or downgraded) from the élite piano bar of the comics to an iniquitously salacious nightclub—has been enjoying a playboy lifestyle, much to the chagrin of both his demonic friend and fellow traveler Mazikeen (here nicknamed Maze) and Amenadiel, the angelic emissary who has been made responsible for getting Lucifer to return to Hell—one way or another. Lucifer is paid a visit by Delilah, a former employee turned pop superstar on something of a downward spiral, and just as Lucifer lifts her spirits, she is promptly gunned down in front of Lux. Lucifer, hell-bent on getting to the bottom of who wanted Delilah dead and subjecting the perpetrator to punishment, crosses paths with Detective Chloe Decker, and the remainder of the episode is given over to the police procedural/buddy cop formula—distinguished by its radical element of the Devil, of course. Along the way, the most significant question raised is the extent to which the Devil remains devilish as he rights wrongs and develops foreign human feelings, which worries Maze, Amenadiel, and Lucifer himself, whose soul-searching in the end brings him to the doorstep of Delilah’s erstwhile therapist, Dr. Linda Martin, to deal with his crisis of conscience.

Detective Chloe Decker

“Attractive female cop struggling to be taken seriously in a man’s man’s world…”

Chloe Decker, the show’s female lead, is introduced as an overcompensating tough female detective with a pesky past that haunts her career, and by the end of the show she becomes not only Lucifer’s partner in crime-fighting but his potential (inevitable?) love interest. Curiously, Chloe is utterly immune to Lucifer’s ability to draw out the naked truth from people, which leads to all sorts of supernatural speculation. (“Did my Father send you?” asks Lucifer.) Particularly interesting is Chloe’s adorable little daughter Trixie, who takes a liking to Lucifer. Might we have a potential Elaine Belloc in the character of Trixie?

Dr. Linda Martin

“I do yoga—hot yoga.”

Chloe and Lucifer come across Linda once Lucifer discovers that Dr. Martin was Delilah’s therapist. Unlike Chloe, Linda is irresistibly drawn to Lucifer, and their lustful exchange before a bemused/disgusted Chloe undeniably makes for the episode’s funniest scene. As comical as this hot-and-bothered therapist may be, she brings an interesting element of depth to the show: just as Linda cannot resist spewing her secrets to Lucifer, she can read Lucifer like no one else can. Lucifer notes to Chloe that while he appeals to “the dark, mischievous hearts” in all women, Chloe is for some reason unbeknownst to him “oddly immune,” and while Lucifer describes her asserted repulsion towards him as “fascinating,” Dr. Martin cannot help but comment that she can tell this deeply disturbs Lucifer. Lucifer’s look betrays his vulnerability, but he ultimately seizes this opportunity to get to grips with his current predicament.

At the end of the episode, Lucifer broods over his burgeoning human emotions—which worry Amenadiel and outrage Maze—and he returns to Linda to discuss “an existential dilemma or two,” laying out a deal which is sure to run throughout the show: in return for Satanic sexual favors she is clearly longing for, Linda will have to take on Lucifer as her patient. This may seem rather unlike the Lucifer of the comics, who is presented as very much self-possessed, but we should keep in mind the one major exception: in the extended treatment of his prelapsarian state, leading up to the heavenly rebellion, Lucifer is shown visiting Lilith—Adam’s first wife and mother of Mazikeen—for someone to discuss his existential angst with.1 If Lucifer in the show will engage in similar discussions about his father issues with Dr. Martin, it could make for both comical and insightful storytelling.

Maze

“…I didn’t leave Hell to be a bartender.”

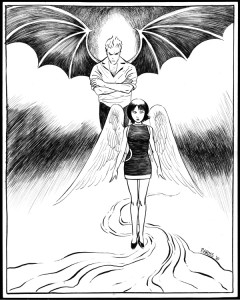

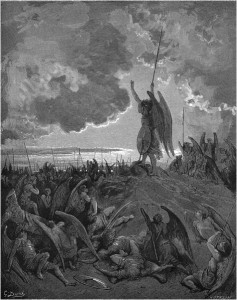

Mazikeen or Maze is presented as Lux’s disenchanted demon bartender. Having expected more from joining Lucifer in his sabbatical, Maze is forthrightly disappointed by the sight of the Lord of Hell whiling away his time indulging in debauched womanizing. More significantly, Maze is deeply disturbed by humanity rubbing off on Lucifer. At the end of the episode, Maze, across from Lucifer, brooding over his growing crisis of conscience, almost desperately barks at her master, “Stop caring. You’re the Devil.” Incidentally, as this incarnation of Mazikeen is rather annoyed over Lucifer not only living a lifestyle she finds beneath his devilish dignity but becoming all-too-human, she wants what Amenadiel wants: Lucifer’s return to Hell. The common ground Lucifer’s angel-brother and right-hand demon-woman share may lead to some spectacular supernatural conflict. In the Lucifer comic, Mazikeen does for a time break with Lucifer and even lead her Lilim army into war against the Morningstar, so a feud between Lucifer and Maze on the show may be in order at some point.

Maze appears briefly in Lucifer‘s Pilot episode, but her character’s significance is sure to grow. Even in the Lucifer comic Mazikeen is at the outset a much smaller character than the hugely significant persona she becomes, evolving from Lucifer’s cowled assistant, whose hidden half-face made her dialogue difficult to discern, into Lucifer’s trusted warrior-woman and true love—a character of such significance, in fact, that she ultimately inherits Lucifer’s mantle, anointed the new Lightbringer by her Lord.2 There was a perfect Mazikeen line from the Pilot script (presumably directed at Chloe) that didn’t make it into the show, but is worth noting: “He’s been my lord and master for over ten billion years. There’s nothing I wouldn’t do for him. I would tear from limb to limb anyone who dares disrespect him. Mind my words.” That sounds just like the Mazikeen from the comic, and it is certainly to be hoped that in dialogue and in action we get to see more of this side of her as the season progresses.

Amenadiel

“I’m not sure I like what I see…”

Amenadiel is here Lucifer’s angelic arch-rival—as he is in the comics, at least until the Morningstar bests Amenadiel in a duel—but here he is also more of a brother figure in a sibling rivalry of cosmic proportions (reserved for Lucifer and Michael in the comic). I mention Amenadiel last because the implications his character raises are rather nefarious. When he first visits Lucifer, Amenadiel implores his brother to return to the Underworld before all Hell breaks loose, but the sentiments he expresses in his second appearance at the end of the episode are far less benign than getting demons and damned souls under control. Amenadiel reveals that he is displeased with Lucifer’s uncharacteristic restraint and mercy, insisting that they must maintain “balance.” In other words, Amenadiel expects Lucifer to go on being the Devil, returning to his assigned role of the Evil One. This seems to imply that the side of Good is not necessarily so good, which is certainly the case in the comics, and it gives force to Lucifer’s earlier question: “Now, do you think I’m the Devil because I’m inherently evil or just because dear old Dad decided I was?”

In Paradise Lost, Milton’s Satan and his rebel angels refer to God with epithets typically reserved for the Devil, such as “enemy” (I.188, II.137) and “foe” (I.122, 179; II.78, 152, 202, 210, 463, 769), and this carried over into Romantic criticism of the poem, Milton’s God cast in a demonic light and the rebel Satan made more sympathetic by comparison. As the Vertigo Lucifer comics truly carry on the Miltonic-Romantic-Satanic tradition, they carry over this ambivalence. The angelic host is fanatically devoted to maintaining the power and influence of the government of Heaven, and Yahweh’s angels are essentially just as indifferent to human life as Lucifer is. Amenadiel himself is rather diabolical in both appearance and motive, even taking the form of a serpent to lead the human prototypes of Lucifer’s own cosmos into temptation.3 As far as the portrayal of Amenadiel in the TV series, it remains to be seen how serpentine he will become (he is certainly less caricatured visually), but I believe the Pilot episode has laid the foundation for that.

Lucifer showrunner Joe Henderson expressed his utmost appreciation for Neil Gaiman’s vocal support for Fox’s effort to bring his character to the small screen. Henderson found particularly apt Gaiman’s observation that creating characters for a company as tremendous as DC Comics is like creating toys in a sandbox, which get left in the sandbox for others to play with. It’s all good and well that Fox is picking up the toys created by Gaiman in The Sandman and played with by Carey in Lucifer, but there is certainly cause for concern over whether or not Fox will place the toys back in the sandbox intact. I understand that translating a sympathetic Satan into the mainstream medium of television necessitates alterations to the source material, but there are certain fundamental things about the Lucifer comic which must be preserved. Mazikeen and Amenadiel are close enough to their comic counterparts, but Lucifer is rather different. Again, I will comment more on this anon, but suffice it to say there is cause for cautious optimism.

To stay on the air, Lucifer is obliged to walk the precipitous tightrope of both exciting sympathy for the Devil whilst evading overly offending the religious. It was perhaps to be expected that the TV-adaptation of Lucifer would simply have to make its titular anti-hero more human than he is in the comic, but the potential pitfall is that Lucifer will be made all-too-human. The Lucifer of the comics is beyond good and evil, whereas the Lucifer of the show grapples with the emerging feelings of goodness within him. Yet oscillating between virtue and vice is a rather Romantic/Byronic dilemma, and so this Lucifer may fall into the Miltonic-Romantic tradition in his own way, however different from his comic incarnation he might be. I will say this: Tom Ellis’ performance of a Lucifer strutting across the L.A. scene announcing “My name is Lucifer Morningstar” and boasting “I’m immortal” is, if nothing else, exceedingly entertaining to watch. I expect this version of Lucifer to be different from the comic version, but I am hopeful that the show will do the Devil justice. Let’s just hope that we don’t all end up as disappointed and angry with Lucifer as Maze…

Notes

1. See Mike Carey, Lucifer: The Wolf Beneath the Tree (New York: DC Comics, 2005), pp. 16, 18, 43.↩

2. See Mike Carey, Lucifer: Evensong (New York: DC Comics, 2007), pp. 68–72.↩

3. See Mike Carey, Lucifer: A Dalliance with the Damned (New York: DC Comics, 2002), pp. 54–67.↩