“The feather of Liberty falls

From the wing of Rebellion…”

— Victor Hugo, La Fin de Satan (1854–62; 1886)

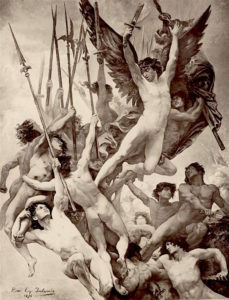

Romantic Satanism was a predominantly English phenomenon, but it did have a significant French manifestation. English Romantic Satanism, however, was far more Miltonic, suffused with the passion and pride which motivated Milton’s Satan in his rebellious individualism and heroic endurance of suffering. The French Romantic Satanists preferred to imagine reconciliation between the damned angel and the Deity,1 whereas in the hands of the English Romantics, Lucifer always remained a rebel defiant to the very end, following his Miltonic predecessor in proudly preferring “an independency of torture / To the smooth agonies of adulation…” (Lord Byron, Cain [1821], I.i.385–86). These different forms of Romantic Satanism reflect the zeitgeist of the separate nations wherein this movement manifested: the French Romantics saw their nation torn asunder by the Revolution and its aftermath; the English Romantics saw their radicalism stamped out by an oppressive establishment that feared the revolutionary spirit crossing the Channel, leaving them seething with a frustrated rebelliousness much akin to that of Milton’s Satan. While I have much more of an affinity for English Romantic Satanism, French Romantic Satanism birthed a rather beautiful symbol which truly encapsulates the significance of Romantic Satanism: the fallen rebel angel Lucifer’s feather of Liberty.

In Victor Hugo’s La Fin de Satan (The End of Satan, 1854–62; 1886), a feather from the archangel Lucifer’s wing falls from Heaven down to our world and becomes Liberty, Lucifer’s angelic daughter—a more positive offspring than Sin, the daughter born Athena-like from Satan’s head in Paradise Lost (II.747–58). Most significantly, Hugo’s Luciferian angel Liberty descends to Earth at the time of the fall of the Bastille in 1789, which launched the epochal French Revolution and ushered in the modern world, thus illustrating just how intertwined Romantic Satanism was with the revolutionary politics of the time.2 For Hugo, the angel of Liberty not only instigates earthly uprisings but enacts the cosmic reconciliation between God and Satan; it is God Himself who brings Lucifer’s feather to life as Liberty, Hugo’s Deity announcing to His damned, despairing angel:

Come; your prison will be pulled down and hell abolished!

Come, the angel Liberty is your daughter and mine:

This sublime parentage unites us.

The archangel is reborn and the demon dies;

I efface the baleful darkness, and none of it is left.

Satan is dead; be born again, heavenly Lucifer!

Come, rise up from the shadows with dawn on your brow.3

All of the shifts Romantic Satanism induced are recalled here: the Devil transforming from angel of evil to father of freedom; the fallen angel repossessing his angelic luminosity and beauty; Satan regaining his native name, Lucifer. The important difference, of course, is that for Hugo these shifts come about through the Devil reconciling with the Deity, whereas English Romantic Satanism restored such luster to Lucifer in all of his defiant magnificence amidst damnation. The latter is more significant because it captures the uniqueness of Romantic Satanism: it was not about the end of Satan but the celebration of Satan; the fallen archangel was idealized not in spite of but because of his rebellion against Almighty God.

While the concept of a cosmic reconciliation between God and Satan is once again wholly at odds with the adversarial “Satanic spirit of pride and audacious impiety”4 at the heart of English Romantic Satanism and its Satanic School, it is nevertheless difficult to resist the poetic power of French Romantic Satanism’s intertwining Man’s revolutionary struggle for freedom with Lucifer’s revolt—so much so that the earthly urge for emancipation is inspired by a token of the heavenly Lucifer’s very being. Hugo’s La Fin de Satan gives the French Revolution a mythical treatment and a poetical sacredness, but its religious air is sacrilegious, its sacredness Satanic. It turns the eagerness of the forces of reaction to demonize the French Revolution on its head by deliberately aligning the Revolution with the Devil, but imagining this as a blessing rather than a curse.

Lucifer’s feather of Liberty is far more appropriate as a symbol for Romantic Satanism than any of the icons which have become familiar representations of Satanism proper: the inverted pentagram, with or without the Baphomet goat head; the inverted crucifix; the 666 “mark of the beast”; etc. The significance of the symbol of Lucifer’s Liberty feather is threefold: 1), it stresses that most important component of the Lucifer myth: the apostate angel’s revolutionary struggle for freedom; 2), it underlines the Romantic refashioning of this liberty-loving Lucifer as beautiful rather than bestial; 3), it designates the luminous rebel angel’s celestial revolt as the inspiration for terrestrial Man’s quest for self-determination. I cannot imagine a more apposite symbol for the phenomenon of Romantic Satanism—and for The Satanic Scholar, the proud preserver of this grand tradition—than Lucifer’s feather of Liberty.

Lucifer’s feather of Liberty is far more appropriate as a symbol for Romantic Satanism than any of the icons which have become familiar representations of Satanism proper: the inverted pentagram, with or without the Baphomet goat head; the inverted crucifix; the 666 “mark of the beast”; etc. The significance of the symbol of Lucifer’s Liberty feather is threefold: 1), it stresses that most important component of the Lucifer myth: the apostate angel’s revolutionary struggle for freedom; 2), it underlines the Romantic refashioning of this liberty-loving Lucifer as beautiful rather than bestial; 3), it designates the luminous rebel angel’s celestial revolt as the inspiration for terrestrial Man’s quest for self-determination. I cannot imagine a more apposite symbol for the phenomenon of Romantic Satanism—and for The Satanic Scholar, the proud preserver of this grand tradition—than Lucifer’s feather of Liberty.

Notes

1. See Maximilian Rudwin, The Devil in Legend and Literature (LaSalle, IL: Open Court Publishing Company, [1931] 1959), Ch. XXII, “The Salvation of Satan in Modern Poetry,” pp. 280–308; Jeffrey Burton Russell, Mephistopheles: The Devil in the Modern World (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, [1986] 1990), pp. 194–200; Ruben van Luijk, Children of Lucifer: The Origins of Modern Religious Satanism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 74–76, 105–08.↩

2. See Russell, pp. 196–200; Ruben van Luijk, “Sex, Science, and Liberty: The Resurrection of Satan in Nineteenth-Century (Counter) Culture,” in The Devil’s Party: Satanism in Modernity, ed. Per Faxneld and Jesper Aa. Petersen (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 45; van Luijk, Children of Lucifer, pp. 81–82, 107–08.↩

3. Victor Hugo, La Fin de Satan, quoted in Russell, p. 200.↩

4. First-generation Romantic radical turned reactionary Poet Laureate Robert Southey’s characterization of Romanticism’s “Satanic School” in his Preface to A Vision of Judgement (1821). Quoted in C. L. Cline, “Byron and Southey: A Suppressed Rejoinder,” Keats-Shelley Journal, Vol. 3 (Winter, 1954), p. 30.↩