“The Satanic Scholar” struck me as an appropriate moniker for the resource dedicated to preserving the tradition established by the Satanic School of English Romanticism. Truth be told, I hold the name/title Lucifer in much higher regard than Satan, though I am obliged to more often invoke the latter, which abounds in the field of Miltonic-Romantic Satanism: e.g., “Milton’s Satan,” “Romantic Satanism,” “the Satanic School,” (Miltonic) “Satanists” and “anti-Satanists.” Be that as it may, this grand tradition—despite the frequency with which the name Satan appears in it—restored not only the fallen angel’s celestial luster, but also his luminous name, which I find both aesthetically and philosophically fitting.

The tradition of the Devil having possessed the name Lucifer (Latin for “Light-Bearer”) before falling from Heaven and being rechristened Satan (Hebrew for “Adversary”) was the product of the early Christian Church, when the concept of the Devil was in its infancy. Lucifer signified the prestigious celestial status the fallen angel once possessed and forever lost1—an interesting addition to the cosmic cautionary tale. The name Lucifer originates from the fourteenth chapter of the Old Testament Book of Isaiah, which the Church Fathers absorbed into the Satanic biography beginning to take shape to further flesh out the character of the Devil, who was to play a major role in Christian theology.

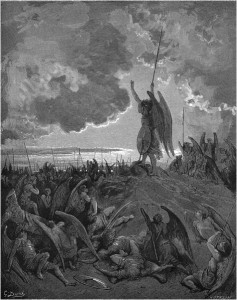

Patristic exegesis of Isaiah 14 concretized the Devil’s prelapsarian name and the sin of prideful ambition to godhead that led him to forfeit it. “How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning!” thunders the biblical prophet Isaiah, “For thou hast said in thine heart…I will exalt my throne above the stars of God.…I will be like the most High. Yet thou shalt be brought down to hell, to the sides of the pit” (Isaiah 14:12–15). The extravagant imagery employed by Isaiah to overstress the overriding pride and commensurate downfall of “the king of Babylon” (Isaiah 14:4) led patristic writers to conclude that the king himself, rather than the vivid language used to describe his spectacular fall from the seat of power, was figurative—a mortal means to describe the Devil’s supernatural fall from grace. For the Church Fathers, Isaiah’s diatribe revealed that Satan became Satan because he aspired above his station, Lucifer the angelic rebel having established himself as simia Dei,2 arrogating divine attributes in his blasphemous ambition to “be like the most High” (Isaiah 14:14).3

Lucifer, as invoked in Isaiah 14:12, is Latin for “light-bearer,” and the original Hebrew reads Helel ben Shahar, “Day Star, son of the Dawn.” It is a reference to Venus, the Morning Star, which is the light-bringer, appearing to herald the light of the rising Sun. Day Star transitioned into Lucifer in Latin translations of the Bible, such as St. Jerome’s fourth-century Latin Vulgate Bible. All English translations of the Bible familiar to Milton4 maintained Lucifer as a proper name, and Milton stuck to this tradition in Paradise Lost,5 retelling the traditional story he inherited as best it could be told. “Lucifer… / (So call him, brighter once amidst the Host / Of Angels, than that Star the Stars among)…” (VII.131–33), relates the archangel Raphael, who alternately emphasizes that—like all fallen angels, who’ve had their names “blotted out and ras’d / By thir Rebellion, from the Books of Life” (I.362–63)—the ruined archangel was stripped of his honorific: “Satan, so call him now, his former name / Is heard no more in Heav’n” (V.658–59).

Traditionally, Lucifer was the highest angel in Heaven, second only to God Himself,6 and despite the qualification Milton places upon Lucifer’s heavenly rank—“he of the first, / If not the first Arch-Angel”7 (V.659–60)—the angelic aristocrat’s celestial status is attested to by Milton’s emphasis on splendor denoting rank in the hierarchy of Heaven. Milton affirms that “God is Light” (III.3; cf. 1 John 1:5), as well as the “Fountain of Light” (III.375), God’s angelic sons the “Progeny of Light” who are by the Almighty “Crown’d…with Glory” (V.600, 839). The title of Light-Bearer thus signifies just how “great in Power, / In favor and preëminence” (V.660–61) the prelapsarian Lucifer was—a point emphasized by Raphael/Milton:

…great indeed

His name, and high was his degree in Heav’n;

His count’nance, as the Morning Star that guides

The starry flock… (V.706–09)

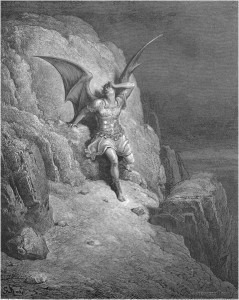

In spite of how illustriously highborn he was in Heaven, “great Lucifer” (V.760), who “sdein’d subjection, and thought one step higher / Would set [him] highest” (IV.50–51), finds himself cast down into “utter darkness… / As far remov’d from God and light of Heav’n / As from the Center thrice to th’ utmost Pole” (I.72–74). Heaven’s erstwhile Morningstar is outcast and reduced to “the Prince of Darkness” (X.383).

The supernal splendor Lucifer once enjoyed intensifies his loss, for though the fallen archangel nobly refuses to “repent or change, / Though chang’d in outward luster” (I.96–97), exchanging the lost glory of his person for the glory of his will,8 he is obviously chagrined by his “faded splendor wan” (IV.870), particularly in the presence of divine radiance. Milton’s fallen Lucifer, “And thence in Heav’n call’d Satan” (I.82), laments his loss of luster in his apostrophe to the Sun atop Mt. Niphates:

…O Sun…how I hate thy beams

That bring to my remembrance from what state

I fell, how glorious once above thy Sphere;

Till Pride and worse Ambition threw me down

Warring in Heav’n against Heav’n’s matchless King… (IV.37–41)

As close as Milton ostensibly stuck to tradition in his portrayal of Lucifer/Satan, he undeniably took radical departures. In Paradise Lost, Milton’s Satan is Lucifer in all but name.

Notes

1. See Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, [1977] 1987), pp. 195–97; The Prince of Darkness: Radical Evil and the Power of Good in History (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, [1988] 1992), pp. 43–44; Neil Forsyth, The Old Enemy: Satan and the Combat Myth (Princeton: Princeton University Press, [1987] 1989), pp. 134–36; The Satanic Epic (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), pp. 51–54, 80–81; Luther Link, The Devil: A Mask without a Face (London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 1995), pp. 22–23; T. J. Wray and Gregory Mobley, The Birth of Satan: Tracing the Devil’s Biblical Roots (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), pp. 108–10.↩

2. See Maximilian Rudwin, The Devil in Legend and Literature (LaSalle, IL: Open Court Publishing Company, [1931] 1959), Ch. XII, “Diabolus Simia Dei,” pp. 120–29.↩

3. See Russell, The Devil, pp. 195–97; Satan: The Early Christian Tradition (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, [1981] 1987), pp. 130–33; The Prince of Darkness, pp. 78–80; Stella Purce Revard, The War in Heaven: Paradise Lost and the Tradition of Satan’s Rebellion (Ithaca, NY and London: Cornell University Press, 1980), pp. 32–35, 47–49; Forsyth, The Old Enemy, pp. 134–39, 370–71; The Satanic Epic, pp. 44–45, 51–54, 80–81; Link, pp. 22–27; Wray and Mobley, pp. 108–12; Henry Ansgar Kelly, Satan: A Biography (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), pp. 191–99.↩

4. See Matthew Stallard, ed. Paradise Lost: The Biblically Annotated Edition (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2011), p. xxix.↩

5. Some critics insist that Milton did not intend his references to Lucifer in Paradise Lost to be understood as Satan’s angelic name in Heaven, but rather as a means of denoting Satan’s erstwhile splendor, for his heavenly abode is referred to as “The Palace of great Lucifer, (so call / That Structure in the Dialect of men / Interpreted)” (V.760–62), his hellish abode “Pandæmonium, City and proud seat / Of Lucifer, so by allusion call’d, / Of that bright Star to Satan paragon’d” (X.424–26). Despite this, I believe it is safe to assume that Milton was conforming to Christian tradition with regards to the change of names from Lucifer to Satan. In his outlines for Adam Unparadiz’d—the verse drama Paradise Lost was originally planned to be—Milton refers to the Devil as Lucifer rather than Satan. See Barbara K. Lewalski, ed. Paradise Lost (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2007), “Appendix: Sketches for Dramas on the Fall, from the Trinity Manuscript,” pp. 341–43. Additionally, Milton referred to Lucifer at various points in his political polemics, in part to add emphasis to his message against men imitating the sin which led to Lucifer’s loss of his illustrious name: prideful aspiring above one’s sphere. See Frank S. Kastor, Milton and the Literary Satan (Amsterdam: Rodopi N.V., 1974), p. 49.↩

6. See Jeffrey Burton Russell, Lucifer: the Devil in the Middle Ages (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, [1984] 1986), pp. 173–74.↩

7. In the traditional Christian hierarchy of angels—seraphim, cherubim, thrones, dominions, virtues, powers, principalities, archangels, angels—Milton’s Satan would be placed second to last in the nine orders. However, although Milton invokes these traditional angelic ranks at various points in Paradise Lost, he does not keep their traditional order. Milton’s archangels are so-called because they are entrusted with tasks of great significance: the archangel Uriel is “Regent of the Sun” (III.690); the archangel Gabriel is “Chief of th’ Angelic Guards” (IV.550) in Eden; the archangel Raphael is placed in charge of educating Adam and Eve about Satan and the danger they are in (V.221–45); the archangel Michael is “of Celestial Armies Prince” (VI.44), is named “the Prince of Angels” (VI.281) on the heavenly battlefield, and is also placed in charge of banishing Adam and Eve from Eden after revealing to the fallen parents of the human race the hope of future salvation (XI.99–125). Just as Milton refers to Satan as “th’ Arch-fiend” (I.156) to emphasize that he is “the superior Fiend” (I.283), so too does he refer to Satan as “th’ Arch-Angel” (I.600) to emphasize his superior angelic rank—“Above them all…” (I.600).↩

8. Milton’s Satan makes repeated reference to the glory of his endeavors: “…the Glorious Enterprise” (I.89); “That Glory never shall his wrath or might / Extort from me” (I.110–11); “…that strife / Was not inglorious, though th’ event was dire…” (I.623–24); “From this descent / Celestial Virtues rising, will appear / More glorious and more dread than from no fall…” (II.14–16); “If I must contend… / Best with the best, the Sender not the sent, / Or all at once; more glory will be won, / Or less be lost” (IV.851–54); “…The strife which thou call’st evil…wee style / The strife of Glory…” (VI.289–90); “To mee shall be the glory sole among / Th’infernal Powers, in one day to have marr’d / What he Almighty styl’d, six Nights and Days / Continu’d making…” (IX.135–38); “…I in one Night freed / From servitude inglorious well nigh half / Th’ Angelic Name, and thinner left the throng / Of his adorers…” (IX.140–43); “…I glory in the name, / Antagonist of Heav’n’s Almighty King…” (X.386–87).

In his narration, Milton himself emphasizes Satan’s relentless pursuit of glory: “…aspiring / To set himself in Glory above his Peers…” (I.38–39); “Him follow’d his next Mate, / Both glorying to have scap’t the Stygian flood / As Gods…” (I.238–40); “And now his heart / Distends with pride, and hard’ning in his strength / Glories…” (I.571–73); “…Satan, whom now transcendent glory rais’d / Above his fellows, with Monarchal pride / Conscious of highest worth…” (II.427–29).↩