Episode 12 of Lucifer, “#TeamLucifer,” was possibly the show’s most satirical episode, within its crosshairs: “generic Satanists.” (To be fair, most of the things these “Satanists” get up to are better described as stereotypical.) The episode opens with a mock ritual sacrifice of a young lady, 19-year-old Rose Davis, at the hands of her boyfriend, Corazon, until the Satanic cult couple’s S&M fun and games becomes an actual murder scene. While Lucifer has been avoiding Chloe for weeks, having discovered that her presence makes him “exsanguinate,” as Lucifer puts it, the detective insists that he helps, as this case demands the Devil’s insight.

Lucifer reluctantly agrees to go along with Chloe, and when he is shown the body of Rose, which has “Hail Lucifer” carved into it, Lucifer remarks, “This is sickening.…I mean, to blame it on me. It’s an atrocity. These Satanists—misguided cult nobheads with Frisbees in their earlobes.” Thus begins the episode’s string of gibes directed at modern occult Satanism. When Chloe and Lucifer discover in Rose’s room a hidden door bookcase that leads to a “creepy, secret evil room,” Lucifer remarks to the sight of chicken remains, “If that’s supposed to be an offering for me, then I decline on the grounds of salmonella.” Lucifer retrieves a Satanic tome from the cobwebby room and, when perusing it, observes, “It’s not half bad, this. I mean, the writing’s atrocious, but it’s not complete drivel. Listen to this: ‘Satan represents a beacon of honesty in a sea of mass self-deceit.’…There’s a whole chapter on sex. I like this book.” This is an obvious reference to The Satanic Bible, written in 1969 by Anton LaVey, who codified modern Satanism and founded the Church of Satan, soon to enjoy its fiftieth anniversary. (Eight of “The Nine Satanic Statements” of LaVey’s Satanic Bible begin with “Satan represents…,” and the book also has a chapter devoted to “Satanic Sex.”)

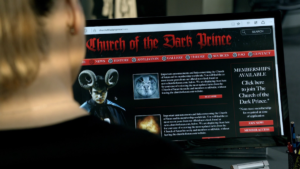

Most satirized by “#TeamLucifer” is Satanism’s penchant for goats. “Why do they always associate me with goats?” scoffs Lucifer when it’s discovered that Rose has subdermal implants spelling out “children of the goat” in Latin. “I mean, I don’t even like their cheese,” the Devil adds. In any event, the goat clue leads to the “Church of the Dark Prince,” which is an obvious parody of the Church of Satan. As Chloe surveys the Church’s website, Lucifer learns that joining requires (like the Church of Satan) a $200 membership fee, to which Lucifer simply states, “Sinful.”

Most satirized by “#TeamLucifer” is Satanism’s penchant for goats. “Why do they always associate me with goats?” scoffs Lucifer when it’s discovered that Rose has subdermal implants spelling out “children of the goat” in Latin. “I mean, I don’t even like their cheese,” the Devil adds. In any event, the goat clue leads to the “Church of the Dark Prince,” which is an obvious parody of the Church of Satan. As Chloe surveys the Church’s website, Lucifer learns that joining requires (like the Church of Satan) a $200 membership fee, to which Lucifer simply states, “Sinful.”

Chloe and Lucifer drop in on the Church of the Dark Prince, wherein its Satanic members are conducting a memorial ritual for Rose. When the Satanist leading the ritual invokes “the four crown Princes of Hell,” Lucifer declares, “This is preposterous…First of all, there’s only one me. And secondly, the whole worship thing is more my Father’s bag.”

Lucifer cannot help but interject when he witnesses a Satanist playing Lucifer in the ritual clumsily march into the room and bump his massive goat head. “This is where I draw the line,” Lucifer erupts, barging into the ceremony. “I’m the real Lucifer and I insist that you stop this nonsense immediately. I mean, have you heard yourselves? It’s embarrassing.…I mean, you preach rebellion, but you’re … you’re misguided sheep. And goat. Where’s the real defiance? The free will?” Some of the Satanists begin to frivolously shout “Yeah! Free will! Free will rules!” and “Anarchy! Woo!” This only irritates Lucifer further, but the Satanists embrace Lucifer as “the best Lucifer we’ve had in years” and proceed to chant his name. “Stop!” Lucifer insists. “Someone killed this girl! She didn’t deserve that. This is not what I stand for. Is that what you all wanted? Eh? Should be ashamed of yourselves.”

But “#TeamLucifer” doesn’t get too preachy, deliberately satirizing itself—the Lucifer show, that is. When Chloe introduces “Lucifer himself” to the hooded doorman at the Satanist meeting to convince him to allow them entry, the doorman bluntly observes, “You’re supposed to be blond.” “Yeah, I get that a lot,” says Lucifer, who is of course in appearance considerably different from his comic book counterpart. Speaking of the Lucifer comic, it is revealed that the real name of Rose’s boyfriend Corazon is Mike Carey, and this Mike Carey is also sacrificially murdered (for fans of Mike Carey’s Lucifer comic, an apt metaphor, surely).

Apart from the satirical lightheartedness of “#TeamLucifer,” the episode does have a more serious side to it. Lucifer, who is rather resentful about being scapegoated for humanity’s sins, is utterly disgusted by the idea of people engaging in such base behavior in his name. What’s worse, Lucifer is asked to excuse himself from the case when it becomes apparent that these Satanic murders may be some twisted tribute to the Devil. “You’re blaming this nonsense on me?” Lucifer indignantly asks. “You really think I’d do these vile things? These kids were pretending to be bad, but they weren’t, they were innocent, so I would never hurt them, I’m not a monster.”

Lucifer’s patience with his bad rap is tested throughout the episode as the Devil is incessantly publicly harassed by a street preacher—the charlatan made a true believer by the sight of the Devil’s face back in the second episode. But Lucifer is at his wit’s end once he’s been taken off the case, and in a moment of rage clutches the preacher by the throat as he voices his irritation with the ingratitude of the humans he’s walked amongst for his “solving [L.A.’s] filthy little crimes.” Malcolm, the criminal cop brought back from Hell by Amenadiel, breaks it up, retiring to Lux with a bemused Lucifer. The disgruntled Devil soon discovers, however, that Malcolm is the mysterious murderer, and the crooked cop, who’s been further twisted by the tortures of Hell, confesses that he has done this to honor Lucifer. “I’m not evil. I punish evil,” insists an infuriated Lucifer. As Lucifer proceeds to begin punishing the evil Malcolm, Amenadiel arrives to pick a fight with his brother for using Mazikeen to manipulate and near assassinate him. Malcolm slips out as the angelic brothers get into a bareknuckle brawl, raising Hell in Lucifer’s penthouse.

As they exchange blows, Lucifer and Amenadiel cast blame upon one another. “You justify it all, don’t you?” asks Lucifer. “Claim it’s all done in the name of our Father, but … it’s for your sake, brother. And they call me the prideful one.” The irate angel insists that this is all Lucifer’s fault on account of his irresponsible refusal to return to Hell, which would allow Amenadiel to return home to Heaven. Lucifer calls into question Amenadiel’s place in Heaven given the havoc he’s wreaked on Earth and his current bad habit of copulating with a demon, which Amenadiel himself finds unsavory. But the brawling angelic brothers are ultimately saved from each other by Mazikeen, who expresses her disgust with both of them, who’ve each used her as a pawn in their respective schemes.

In the closing scene of “#TeamLucifer,” Chloe comes face-to-face with the bruised and bloodied Lucifer, who suspects that Amenadiel has somehow employed the good detective as another weapon in his arsenal. When Chloe asks Lucifer what happened, the fallen angel drifts off into a melancholic monologue:

Well … where do I begin? With the grandest fall in the history of time? Or perhaps the far more agonizing punishment that followed? To be blamed for every morsel of evil humanity’s endured, every atrocity committed in my name? As though I wanted people to suffer. All I ever wanted was to be my own man here. To be judged for my own doing. And for that? I’ve been shown how truly powerless I am. That even the people I trusted … the one person, you … could be used to hurt me.

But as Lucifer reflects on his troubled past and his disastrous current state of affairs, Chloe discovers the corpse of the preacher (presumably Malcolm’s work) beside Lux’s bar. The episode ends with an upset Chloe promptly placing Lucifer under arrest.

It is unclear which direction the impending Lucifer season finale will take. It certainly seems likely that Amenadiel will end up in Hell, perhaps forced to take the infernal throne. It also seems probable that Mazikeen will join Amenadiel there, given their mutual attraction and the demon’s desire to return home to Hell. But what of Lucifer? “#TeamLucifer” hammered home the Devil’s deep disenchantment with his policing the City of Angels, as well as his agitation with his reputation as the Evil One. Lucifer seems to believe that his earthly sojourn has been a failure, so the question remains: what’s left for the Devil to do now?