Romantic Satanism was not about Devil worship, but rather identification with Satan the magnificent rebel angel out of Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667) and adoption of his mythic/poetic revolt against the absolute authority personified in the Almighty as a sociopolitical countermyth. Romantic Satanists were essentially little Lucifers—Miltonic Satans in miniature.

Before Lord Byron found himself implicated in Robert Southey’s Satanic School diatribe,1 English clergyman Reginald Heber had identified in Byron “a strange predilection for the worser half of manicheism,” accusing Byron of having “devoted himself and his genius to the adornment and extension of evil.”2 This, “being interpreted,” reflected Byron himself, “means that I worship the devil…”3 Heber would go on to explain that “Lord Byron misunderstood us. He supposed that we accused him of ‘worshipping the Devil.’ We certainly had, at the time, no particular reason for apprehending that he worshipped anything.”4 Byron’s failure—or refusal, rather—to bend the knee in worship of anything, however, was what made Byron so Satanic, and the same goes for Shelley, the militant atheist who imagined himself very much like the heroically unbowed Satan: “Did I now see him [God] seated in gorgeous & tyrannic majesty as described, upon the throne of infinitude – if I bowed before him, what would virtue say?”5 Just as “narcissists” are simply individuals who bear the likeness of the mythical Narcissus, Byron and Shelley were “Satanists” not because they worshipped the Devil, but because of their likeness to the arch-rebel—an image they often deliberately donned.

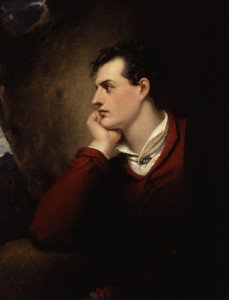

Satanism was certainly at the heart of Byronism, the cultural phenomenon that saw Byron hurled haphazardly into the limelight. “I awoke one morning and found myself famous,”6 Byron stated of the meteoric rise to stardom Cantos I and II of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (1812) afforded him. The poem was largely a success on account of its eponymous hero, who marks the arrival of a truly Satanic character type, the “Byronic Hero,” which Peter L. Thorslev, Jr. considers “the most popular phenomenon of the English Romantic Movement and the figure with the most far-reaching consequences for nineteenth-century Western literature…”7 During his years of fame in English high society, Byron titillated an enthralled public with a series of bold and brooding figures enigmatically treading the line between virtue and villainy. These Byronic Heroes are hallmarks of the poet’s preoccupation with Milton’s Satan, for they were all clearly cast in the mold of Milton’s “Hell-doom’d” (II.697) anti-hero.8 Byronic Satanism would reach its zenith when Byron, in the wake of the public collapse of his ill-suited marriage, was compelled to exile himself from England on account of the cancerous rumors of his scandalous sexual escapades of incest with his half-sister, Augusta Leigh, and indulgence in the capital crime of sodomy. Outcast from the realm of which he was a peer, the tortured Byron produced works so irreverent that he ultimately crafted a Byronic Hero who is not only Satanic9 but Satan himself—or Lucifer, rather.

Byronic Heroes were in part poetic self-portraits, as Byron cultivated a notoriously “mad – bad – and dangerous to know”10 persona—to the point of claiming Satanic status. With ironic Calvinist certainty, Byron asserted that he was not destined for Heaven, but doomed to Hell, viewing his clubbed foot as his own personal mark of Cain. As far as Byron was concerned, his deformed foot may as well have been a cloven hoof. “He saw it as the mark of satanic connection,” relates Benita Eisler in her biography of Byron, “referring to himself as le diable boiteux, the lame devil.”11 Byron’s dogged sense of sin was mostly the product of the perverted form of Calvinism literally beat into him as a young boy by his Scottish nurse, May Gray, who also introduced the young Byron to the sins of the flesh. Being “Majestic though in ruin” (Paradise Lost, II.305) was part and parcel of the Byronic persona, however, and so “Byron seized for himself the starring role of fallen angel,” Eisler explains, “the outcast branded with the mark of Cain.”12

Claiming fallen angel status, Byron went so far as to profess himself literally “a stranger in this breathing world, / An erring spirit from another hurled” (Lara 18.27–28) to his wife, his legendary womanizing presumably the result of having been among those angels of Genesis 6 who descended to Earth to make love to mortal women13—a subject Byron explored in Heaven and Earth (1823). A seething sense of damnation was central to the Byronic persona, for, in the words of Mario Praz, “like Satan, Byron wished to experience the feeling of being struck with full force by the vengeance of Heaven.”14 Byron should hardly have been surprised when Southey accused him of having “rebelled against the holiest ordinances of human society” and establishing a “Satanic School.…characterised by a Satanic spirit of pride and audacious impiety…”15

Notes

1. In the Preface to A Vision of Judgement (1821), Robert Southey wrote: “Men of diseased hearts and depraved imaginations, who, forming a system of opinions to suit their own unhappy course of conduct, have rebelled against the holiest ordinances of human society, and hating that revealed religion which, with all their efforts and bravadoes, they are unable entirely to disbelieve, labour to make others as miserable as themselves, by infecting them with a moral virus that eats into the soul! The school which they have set up may properly be called the Satanic School, for though their productions breathe the spirit of Belial in their lascivious parts, and the spirit of Moloch in those loathsome images of atrocities and horrors which they delight to represent, they are more especially characterised by a Satanic spirit of pride and audacious impiety, which still betrays the wretched feeling of hopelessness wherewith it is allied.” Quoted in C. L. Cline, “Byron and Southey: A Suppressed Rejoinder,” Keats-Shelley Journal, Vol. 3 (Winter, 1954), p. 30.↩

2. Quoted in Peter A. Schock, Romantic Satanism: Myth and the Historical Moment in Blake, Shelley, and Byron (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), p. 101.↩

3. Quoted in ibid., p. 190n. 48.↩

4. Quoted in Clara Tuite, Lord Byron and Scandalous Celebrity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 233.↩

5. Quoted in Schock, p. 80.↩

6. Quoted in Fiona MacCarthy, Byron: Life and Legend (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2002), p. x.↩

7. Peter L. Thorslev, Jr., The Byronic Hero: Types and Prototypes (Minneapolis: Lund Press, Inc., 1962), p. 3. Atara Stein traces the pervasiveness of the Byronic Hero beyond the nineteenth century and into modern popular culture in The Byronic Hero in Film, Fiction, and Television (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, [2004] 2009).↩

8. Childe Harold “would not yield dominion of his mind / To spirits against whom his own rebell’d; / Proud, though in desolation; which could find / A life within itself, to breathe without mankind” (III.12.105–8); the Giaour (“infidel”) was comprised “Of mixed defiance and despair!.… / If ever evil angel bore / The form of mortal, such he wore” (The Giaour [1813] 908–13); Conrad had “a laughing Devil in his sneer, / That raised emotions both of rage and fear” (The Corsair [1814] 9.31–32); Lara “stood a stranger in this breathing world, / An erring spirit from another hurled” (Lara [1814] 18.27–28).↩

9. Manfred, like Milton’s Satan, asserts that “The mind which is immortal makes itself / Requital for its good or evil thoughts— / Is its own origin of ill and end— / And its own place and time” (Manfred [1816–1817], III.iv.129–132); Cain and Lucifer are twin “Souls who dare look the Omnipotent tyrant in / His everlasting face, and tell him, that / His evil is not good!” (Cain: A Mystery [1821], I.i.138–40).↩

10. Lady Caroline Lamb, quoted in MacCarthy, p. 164. Her famous assessment of Byron did nothing to prevent their ill-fated love affair, but perhaps did a great deal to instigate it.↩

11. Benita Eisler, Byron: Child of Passion, Fool of Fame (New York: Vintage Books, 2000), p. 13.↩

12. Ibid., p. 299.↩

13. See Malcolm Elwin, Lord Byron’s Wife (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., 1962), pp. 263, 271, 346.↩

14. Mario Praz, The Romantic Agony, trans. Angus Davidson (Cleveland and New York: The World Publishing Company, [1933] 1963), p. 73.↩

15. Quoted in Cline, p. 30.↩