The Satanic Scholar is dedicated to preserving the Miltonic-Romantic legacy of Lucifer, the radical tradition established by English Romantic Satanism and its Satanic School: the spirited celebration of Milton’s Satan as a veritable Promethean champion of laudable revolutionary virtues.

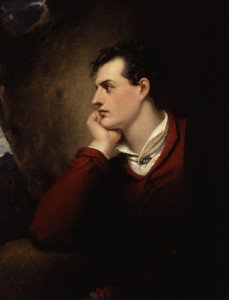

As The Satanic Scholar, I follow in the irreverent footsteps of Romantic icons Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley, who were castigated as heads of a “Satanic School” in 1821 by Poet Laureate Robert Southey, a first-generation Romantic radical turned reactionary. Southey condemned these wayward second-generation Romantic poets for having “rebelled against the holiest ordinances of human society” to the point of alliance with the fallen archangel out of Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), inspired as their works were by “a Satanic spirit of pride and audacious impiety…”1 Byron—the primary target of Southey’s diatribe, and a bitter rival—was dismissive of the Satanic branding: “…what is the ‘Satanic School?’ who are the Scholars?.…I have no school nor Scholars…”2 Despite his denial, Byron, along with Shelley, was at the forefront of a Satanic School, and I pride myself on being its Scholar.

I have found it to be my calling to bear the torch of the Satanic School. As the keeper of the Miltonic-Romantic-Satanic flame, I deem Milton’s “Apostate Angel” (I.125) nothing less than “the hero of Paradise Lost”3 and, for his singularly “daring ambition and fierce passions,” celebrate Milton’s Satan as “the most heroic subject that ever was chosen for a poem…”4; I find that the “only imaginary being resembling in any degree Prometheus, is Satan,”5 and boast Milton’s Satan unexceeded in “energy and magnificence”—even by the Deity Himself, to whom “Milton’s Devil as a moral being is…far superior…”6; I cherish the Miltonic-Romantic Satan brought to life in the visual arts as a humanized and heroicized figure by the likes of Henry Fuseli, Thomas Stothard, James Barry, Richard Westall, Sir Thomas Lawrence, William Blake, John Martin, and “the last of the Romantics,” Gustave Doré. Theirs was the handsome Devil of heroic proportions imagined by Milton, these artistic geniuses exchanging the traditional Satan’s grotesque horns and hooves for classical beauty, an athletic physique, and a passionate mien, the awe-inspiring artistic tradition of the Satanic sublime reaching its apex in Spanish sculptor Ricardo Bellver’s El Ángel Caído (The Fallen Angel, 1877). I take great pride in safeguarding this grand tradition, which restored luster to Lucifer’s much tarnished name and face.

Like the Romantics, I was quite overwhelmed when I first encountered the eloquent fallen angel found in the pages of Milton’s Paradise Lost, awestruck by Satan’s heroic defiance, though “Hell-doom’d” (II.697). It swiftly occurred to me that I was, to cite Blake’s famous line, “of the Devil’s party without knowing it,”7 and so I discovered my affinity with the Romantic radicals who laid claim to Milton’s Satan as one of their own, magnifying their own diabolical dispositions. Over a decade ago, an immersive study of diabology in general and Miltonic-Romantic Satanism in particular led me to intellectual enrollment in the Satanic School, as it were. A diabolical autodidact with of course no actual Satanic School to attend, I transformed my undergraduate and graduate work into ventures in Satanic studies, ultimately teaching Milton’s Paradise Lost and its Satan controversy at my alma mater.

This site is the product of the independent scholarship of a seasoned neo-Romantic Satanist, one who identifies with that “Satanic spirit of pride and audacious impiety” pervasive in the poetry, prose, and politics of Byron, Shelley, and their circle. In fact, I daresay I feel the “Satanic spirit” more intensely, for while the Romantics expressed occasional reservations about Milton’s “proud / Aspirer” (VI.89–90), I believe wholeheartedly that the magnificent Miltonic Satan should be set upon a pedestal.

One simply cannot overstress the significance of the Romantic legacy of Lucifer, which enlisted a number of the era’s most titanic intellectuals, poets, prose writers, and visual artists. Romantic Satanism was rooted in the eighteenth-century intellectual circle presided over by radical publisher Joseph Johnson (which included Thomas Paine, Mary Wollstonecraft, William Godwin, and William Blake), and the movement reached its apex in the early nineteenth-century Satanic School of Byron and Shelley. Romantic Satanists celebrated Milton’s Satan, with his “dauntless courage” in the face of “the Tyranny of Heav’n” (I.603, 124), as the sublime hero of Paradise Lost and an illustrious symbolic standard-bearer for unfettered humanity. Southey’s demonization of Byron and Shelley was undeniably inclined to hyperbole (“Men of diseased hearts and depraved imaginations.…labour to make others as miserable as themselves, by infecting them with a moral virus that eats into the soul!”8), but the paranoid Poet Laureate was nevertheless remarkably accurate in his charge of Satanism.

The Byronic/Shelleyan penchant for channeling the spirit of Milton’s arch-rebel and putting his celestial revolt to earthly use as a sociopolitical countermyth has had a greater impact on the Morningstar’s majesty than the proceedings of any occult order.9 Indeed, Romantic Satanism’s reevaluation of Milton’s Satan can truly be said to have mirrored the Miltonic mutiny of the angels, as Romantic Satanists challenged Judeo-Christian authority and exalted the fallen archangel to godlike glory as an idealized iconoclast in the face of the Almighty—or at least His mortal representatives wielding ecclesiastical and secular power. One may rightly be tempted to conclude that Romantic Satanism realized on Earth what the mythic Lucifer had vainly attempted in Heaven.

The tradition of Romantic Satanism became somewhat endangered as it came under heavy fire in the twentieth century, but Romantic sympathy for the Devil endured in the writings of those literary critics who continued to defend Milton’s Satan as a noble rebel against divine despotism, and who were accordingly (and appropriately) categorized as “Satanists.”10 While the Miltonic-Romantic-Satanic flame flickered in the twentieth century, it shows signs of new life in the twenty-first, and I intend to report modern-day sightings of the Miltonic-Romantic Satan and his influence on our cultural milieu. Significantly overt examples include the Paradise Lost film, which, despite numerous failures to launch over the past decade, I imagine will soon be successfully resurrected, and, more immediately, the Vertigo Comics series Lucifer (1999–2006), soon to enjoy a loose television adaptation on Fox. I cite these particular examples because they seem to indicate that it is the fallen Morningstar’s time to shine: such echoes of Miltonic-Romantic Satanism expose or will expose mass audiences to an idealized Devil largely absent from popular culture, hitherto predominantly saturated with Satans of the medievally monstrous or lightheartedly comical variety.

Asserting oneself as the Devil’s defender is an unusual gesture, contemporary Satanic circles notwithstanding. In doing so, I defy both religionists and secular humanists, who would like to see Satan forsaken to the pit of Hell or discarded into the dustbin of history, respectively. Why promote myself to the peculiar position of Satanic Scholar? It would be more difficult for me to imagine why I wouldn’t. Like Paradise Lost’s fallen cherub Azazel, who claims the “proud honor” of unfurling Satan’s “mighty Standard” (I.533), I can think of no more worthwhile vocation than honoring the memory of “the sublimest creation of the mind of man,”11 the majestic Miltonic Satan. To perpetuate the legacy of the Heaven-defying, liberty-loving Lucifer radically apotheosized12 by Romantic Satanism and its Satanic School is not only a worthwhile endeavor, but one which makes me—to cite the old proverbial phrase—as proud as Lucifer.

— Christopher J. C.

Notes

1. Quoted in C. L. Cline, “Byron and Southey: A Suppressed Rejoinder,” Keats-Shelley Journal, Vol. 3 (Winter, 1954), p. 30.↩

2. Quoted in ibid., p. 35.↩

3. Lord Byron, quoted in Jerome J. McGann, Don Juan in Context (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976), p. 25; Percy Bysshe Shelley, Preface to Prometheus Unbound (1820), in Shelley’s Poetry and Prose, ed. Donald H. Reiman and Neil Fraistat (New York [2d rev. ed. 1977]: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2002), p. 207.↩

4. William Hazlitt, Lectures on the English Poets (1818), “Lecture III: On Shakespeare and Milton,” in The Romantics on Milton: Formal Essays and Critical Asides, ed. Joseph Anthony Wittreich, Jr. (Cleveland: The Press of Case Western Reserve University, 1970), p. 384.↩

5. Shelley, Preface to Prometheus Unbound, p. 206.↩

6. Percy Bysshe Shelley, A Defence of Poetry (1821), in Shelley’s Poetry and Prose, p. 526.↩

7. In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790–93), Blake famously wrote: “The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devils party without knowing it[.]” William Blake, The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman, rev. ed. (New York: Anchor Books, [1965] 1988), p. 35; pl. 6.↩

8. Quoted in Cline, p. 30.↩

9. In “The ‘Satanism’ of Blake and Shelley Reconsidered,” Studies in Philology, Vol. 65, No. 5 (Oct., 1968), pp. 816–33, Joseph Anthony Wittreich, Jr., despite his argument that Romantic Satanism is a grossly exaggerated movement, highlights the fact that Southey’s Satanic School diatribe for the first time in history employed the “Satanist” accusation most appositely, i.e., against actual Satanic sympathizers: “The terms ‘Satanist’ and ‘Satanism’ have historical liaisons that take us as far back as the Renaissance. During the sixteenth century these terms were used first in reference to the dissenters (1559), then the Arians (1565), and finally the Atheists (1589). By linguistic extension, ‘Satanism’ was broadened in the seventeenth century to include any devil-inspired doctrine or anyone with a diabolical disposition. Robert Southey, however, is the first to link Satanism with the Romantics, specifically Byron.…In our time, through linguistic specialization, ‘Satanism,’ with its full range of historical meanings, has come to refer specifically to the Romantic critics of Paradise Lost and more generally to those critics who evince a strong ethical sympathy for Satan” (pp. 817–18).↩

10. The most thorough definition of Miltonic Satanists is given by the anti-Satanist John S. Diekhoff in Milton’s Paradise Lost: A Commentary on the Argument (New York: The Humanities Press, Inc., [1946] 1963): “The literary heretics who have thought Satan the central figure in Paradise Lost, who have regarded him as a thoroughly admirable moral agent, and who have thought that Milton consciously or unconsciously, more or less, identified himself with Satan, have been classified together under the label Satanists” (p. 29).↩

11. George Cilfillan, quoted in Merritt Hughes, Ten Perspectives on Milton (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1965), p. 176.↩

12. In Romantic Satanism: Myth and the Historical Moment in Blake, Shelley, and Byron (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), the only book-length treatment on the subject, Peter A. Schock over and again asserts that the apotheosis of Milton’s Satan in Romantic Satanism made for an apotheosis of humanity: “…the apotheosis of human desire and power” (3), “the apotheosis of human will and consciousness” (26), “the apotheosis of human desire” (36), and “an heroic apotheosis of human consciousness and libertarian desire…” (39).↩