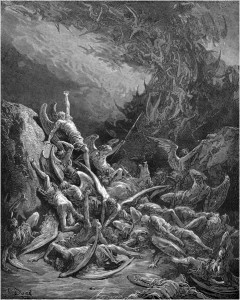

After the years of silence which followed preproduction of the Scott Derrickson-directed Paradise Lost film, it was announced on September 16 of 2010 that Alex Proyas—the visionary director behind such films as The Crow (1994), Dark City (1998), and I, Robot (2004)—had been given the directorial reins of the Paradise Lost project, described as “the story of the epic war in heaven between archangels Michael and Lucifer, and…crafted as an action vehicle that will include aerial warfare, possibly shot in 3D.” The prospect of a 3D Paradise Lost film seemed far too gimmicky to me, but the goal was obviously to follow in the footsteps of the groundbreaking Avatar (2009), immersing IMAX audiences in the fantastical world the filmmakers create—which, in the case of Paradise Lost, would take moviegoers on a promising cosmic tour through Heaven, Hell, and Eden.

Under Proyas, Paradise Lost began picking up steam in ways the project never had with Derrickson at the helm, especially when news broke on May 4 of 2011 that rising star Bradley Cooper would be playing the Miltonic Lucifer himself, Cooper wasting no time to enthusiastically advertise the project on media outlets like Charlie Rose when promoting The Hangover: Part II. In July of 2011, Proyas and Cooper appeared at the San Diego Comic-Con to promote Paradise Lost, then in preproduction, the director expressing his aspiration to live up to Milton’s epic poem:

Basically, this film is based on Milton’s Paradise Lost, a seventeenth-century epic poem. We’re pretty much going to live up to that. We’re going to make this incredible, epic film about the war of the angels, Lucifer’s fall from grace, his battle with the archangel Michael. So it’s a pretty big canvas, and I hope we can live up to that.

Proyas demonstrated that he was the first person attached to the Paradise Lost project to truly understand the gravity of the endeavor of adapting Milton’s vast vision to the screen:

We try to stay as faithful as we can. In fact, we have one particular Milton scholar [Eric C. Brown] who’s been working with us, to keep us in check, to make sure we’re doing the right thing. But I think we achieved a great narrative within the scope of Paradise Lost. It’s been a bit of re-editing the flow of the story, but I think it’s working very well now.…When you go into something as deep and as beloved as Milton’s Paradise Lost, you try to be as respectful of the source material as possible. We were actually surprised by how respectful we had been. We were very pleased by the reception that the script got. So that was a real great surprise.

As overjoyed as Proyas was about the onscreen supernatural spectacle he would be able to play with, the director expressed that he was far more enthused about the opportunity to bring one of English literature’s greatest characters to life on the silver screen: “The story and the characters are really the thing for me…That’s what gets me excited, and I think particularly with Lucifer we have a really wonderful opportunity to create the most extraordinary character that we’ve never seen on film before.”

Despite the heartfelt excitement expressed by both Proyas and Cooper, as well as the considerable progress the audacious project had made, the Paradise Lost film was once again simply not meant to be. Discussing the technological innovations required to properly adapt Paradise Lost to the medium of cinema, Proyas ominously stated, “This film couldn’t have been made a few years ago, and in fact we’re not even sure we can make it now.” The Comic-Con crowd laughed along with Proyas, who reassured the audience, “We’re hoping we can,” but the would-be Paradise Lost director’s words rang true. While the project continued to advance, with casting news popping up throughout the summer and fall of 2011—Benjamin Walker as the archangel Michael, Djimon Hounsou as Abdiel (here “the Angel of Death”), Casey Affleck as Gabriel, Camilla Belle as Eve, Callan McAuliffe as Uriel, Dominic Purcell as Jerahmeel/Moloch, Diego Boneta as Adam, Sam Reid as Raphael, and Rufus Sewell as Samael—principal photography for the film was repeatedly delayed at the tail end of 2011. There was talk about attempts to reduce the cost of the production so that it would not exceed $120-million, but Legendary Pictures finally pulled the plug on Paradise Lost in early 2012, and the project has remained in limbo ever since, bits and pieces of concept art and storyboards emerging every so often to show viewers what the film might have looked like.

I imagine my former Miltonist Professor from about a decade ago was relieved. “Miltonists have not traditionally been interested in popularizing, in the way Shakespeareans have,” explained Milton in Popular Culture co-editor Gregory Colón Semenza to Michael Joseph Gross in his March 4, 2007 New York Times article on the Paradise Lost film. Semenza added, “there’s the sense that Milton is the last figure that can be protected from the tentacles of pop culture, so there is some resistance to this movie…” To a certain extent, I understand this, particularly as someone who is concerned with preserving the Miltonic-Romantic Lucifer’s legacy. Having Milton’s sympathetic Satan dominate the silver screen as the star of a blockbuster film is an incredibly thrilling notion, but of course there is the risk that the filmmakers will fail to do the Devil proud, which is reason enough for me to be somewhat apprehensive. (After all, consider what happened when Vertigo Comics writer Mike Carey’s Lucifer was brought to the small screen.)

There were certainly reasonable concerns that “the tentacles of pop culture” threatened the endeavor of a Paradise Lost film. (Watching the tragic Fall of Man with 3D glasses on just doesn’t seem appropriate to me…) What’s more, that this mega-budget attempt at bringing Milton’s multifaceted masterpiece to the big screen was being headed by several filmmakers who were either novices or whose films were hit-or-miss was cause for concern as well. Failure to properly bring Milton’s Lucifer to life would transform the prime example of the fallen archangel’s current cultural ascension—what I identify as a nascent neo-Romantic Satanism—from a blessing into a curse. And as far as the Miltonic-Romantic-Satanic tradition is concerned, a misguided film adaptation of Paradise Lost would be a lasting blemish, as, once released, a remake of Paradise Lost emerging any time soon thereafter would be highly unlikely, and even then there is no guarantee a subsequent attempt would get it right either.

It’s been nearly a half-decade since Legendary Pictures shut down Paradise Lost, but I imagine the project will reemerge at some point within the next half-decade. (Producer Vincent Newman apparently made an attempt to start things up again in 2014, “determined to finish it ‘sooner than later.’ ”1) Despite the apparent danger of making a movie out of Milton’s Paradise Lost, I still believe this film is something that needs to happen at some point, as the Miltonic-Romantic Lucifer must at long last stake his flag on cinematic soil, which has up to this point been predominantly saturated with Satans either medievally monstrous or lightheartedly comical. I can only hope that the Milton scholar employed as a script consultant on the film was as impressed by the project’s faithfulness to the spirit of Milton’s poem as Proyas claimed he was.

Notes

1. See Eric C. Brown, Milton on Film (Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press, 2015), p. 332.↩